The Zone, 2011

“Everything here becomes visible. Everything can be seen, as if danger could add to the excitement. The period of desolation is past, and photography can capture the urgency and the chaos of life. Guillaume Herbaut prefers a style that is realistic without appearing to be naturalistic. It is a distinctive style: images overstate and intensify situations, imposing their own time signature. Nothing exists as it actually is. The photographer’s job is to bring substance to what is real.

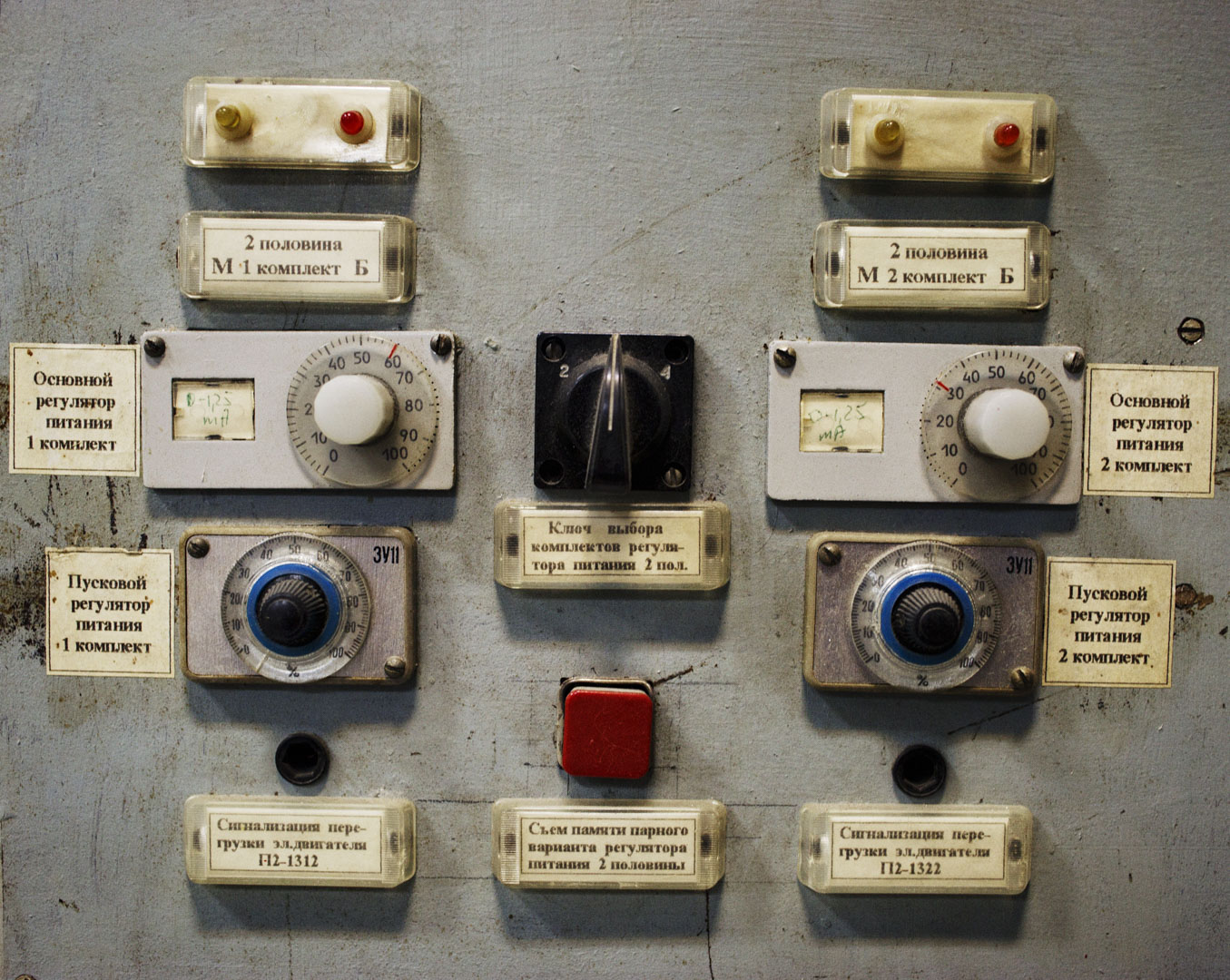

In the Zone, danger, as seen, has changed. It is no longer toxic radiation, but rather the squalor of the human condition which produces its own effects: victims of fate have disappeared, while the poor and wretched have appeared. Here, in the Zone, Guillaume Herbaut brings photography into the imaginary realm of the Russian novel, of a Dostoyevsky novel. As a photographer, he focuses on people, figures, faces, types. The Zone has provided him with the ideal setting to build his world of feelings: at a loss, conflicting hopes, in a world that can be grotesque.

As always it is the spaces between the images, together with the voice in his log book, that establish a world of legend. As always, Guillaume Herbaut creates a distance. His role might be compared to the position of a stage director who may find emblematic locations where the limits of human life stand out to be observed. This is far removed from any photo-essay intended to expose or even inform. There is not the compassionate involvement of the humanistic or humanitarian tradition. These are simply characters snared in their inextricable fate, as wretches.”

-Michel Poivert – Photography Historian

“There, in front of me, I can see the bridge covered in snow, the blue-tinged light at night, and wolf tracks. I have been in the Chernobyl exclusion zone for two days. I never wanted to go back. I had spent too much time there between 2009 and 2011, a total of four months wandering and getting lost in this forbidden land which had fascinated me ever since my first journey there in 2001. I am both attracted and repelled. There is fear of the high-contamination area. The Zone is now a place for me to stop and think. I’m not interested in Chernobyl any more; I’m not interested in what happened in the past or in the after effects. I just want to close my eyes and forget. But there, I can still see Piotr walking through the snow, about to cross the no-go area, to steal metal, contaminated metal. I can hear Igor telling me that he’ll be my shadow. I can see Larissa taking off her clothes in the hotel in Ivankov: “Why do I do it?” And I can smell the alcohol on the breath of the militiamen. “We were furious. If we’d caught you in the zone and arrested you, we would have got a bonus.” I can see Vladimir singing, and making me drink until I was sick. In the alcoholic fog, I can see a man being attacked, and hear the thud when his skull hits the ground. And I can hear my radiometer shrieking, telling me not to stay.

Chernobyl has been rattling my brain, making me lose my bearings, and even today it is still difficult to get it out of my mind. And there is the bridge, and the wolf tracks in the snow, the water, dark and deep, the Uzh River. I have to get away. One step too far, something’s happened, I can feel the icy water biting into me, and realize that there was a hole beneath the snow. I’ve hurt my shin. Nothing serious, just a scare. But this has finally proven to me that the journey has got to come to an end.

In 2001, Chernobyl made me change from black & white to color, from movement to a frontal approach. Basically I went from reporting to documentary work, which made me think about my attitude to photojournalism. In 2009, Chernobyl was an opportunity to contemplate a real situation as raw material, where I could drown myself, pushing on the sense of fiction, and getting away from a straight photo.

Over time, Chernobyl became a reference point, standing like a beacon, with a morbid light shining out.”

-Guillaume Herbaut