The river ran black: The end of the coal, 2020-2022

My grandparents settled in the mining basin of Asturias, Spain, in the 1950s. A time when coal mining was the engine of economic development in the region.

My father grew up in these narrow valleys surrounded by mountains, where the river ran black and where the sound of the siren announced the descent of the workers into the depths of the Earth.

From 1985 began a great cycle of general strikes intended to prevent the industrial desertification of the mining basins. Despite this movement, Spain’s entry into the European Economic Community triggered the countdown to the definitive closure of the mines. In 2023, that of San Nicolás will cease its activity, sealing the end of the history of coal in Spain.

This decline has marked the landscape and the population. The rusting mining towers still stand as nature reclaims the space. In the villages, hundreds of houses and businesses have closed their shutters. Young people leave for lack of job prospects and those who stay remember with nostalgia the years when the region attracted workers from all over Spain, and when a strong associative life flourished.

Born in Madrid, far from these northern lands loaded with the symbolism of the workers’ struggle, I wanted to return to the place where my paternal family was born, to photograph the end of an era and collect the stories of the last miners.

Today the river runs clean and yet, every day, there are fewer people to admire it.

At the age of 9, Thais Mellado’s life took a decisive turn. Her father, whom she adored, lost his life in the mine, crushed under a rock. Alongside her older sister, she grew up in absolute poverty, while her mother worked tirelessly as a cleaning lady. The decline of industry and the scarcity of jobs in the Asturian coalfields created an increasingly difficult situation.

Faced with this panorama, when the Hunosa mining company offered her a job on the condition of absolute preference, giving priority to the children of miners who had died in industrial accidents, she didn’t hesitate to seize the opportunity. Today, with over 15 years of dedication to the mine, Thais proudly heads her team in San Nicolás, standing out as one of the brave women who resist in this predominantly male world.

Artemio Fernández was born in a small village in the Turón valley in the midst of the Spanish Civil War. He grew up in the poverty and deprivation of the post-war period. Lacking financial resources, he was unable to complete his studies and began working in the San Víctor mountain mine. In those days, there were no work uniforms or showers on site. Artemio remembers how he would run down the mountain at the end of his working day, his clothes soaked with sweat, and then bathe with a bucket of cold water on the way home.

After his retirement, he decided to devote his remaining years to his great passion: singing. He joined the Turón Mining Choir and, now in his eighties, travels the world with a group of former miners, dressed in their hard hats and work clothes, singing the songs of the mine and earning the nickname of guardians of mining history. His voice becomes a living testimony to the past, preserving the legacy and memory of the mining industry that so profoundly affected them.

Manuel Cadenas became a minor at just 16 years of age. Life forced him to run fast, as he had already been a war refugee in Paris and an orphan. Without a mother and with a sick father, the hard, dark and deadly mine was, paradoxically, his salvation. He started out as a “guaje”, a miner’s helper, in the San Víctor mountain mine in the Turón valley. Nine hours a day, seven days a week.

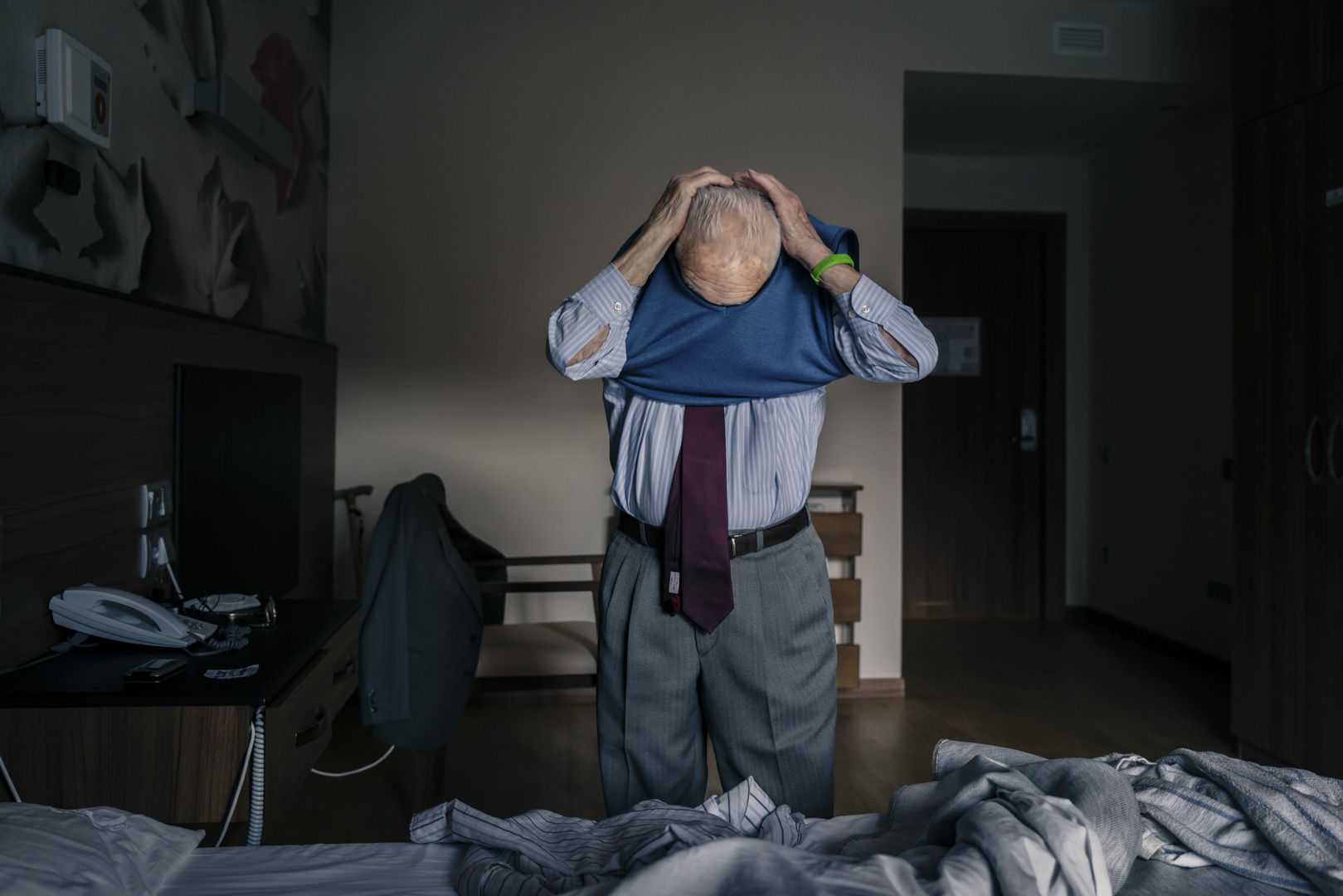

Accidents were so frequent that they inspired Manuel, who combined his job as a miner with nursing studies for a decade. He then worked in the company hospital until his retirement 40 years later. Today, at 98, he lives in the Montepio retirement home in Felechosa, a place designed so that former coal miners can spend their last days surrounded by the mountains where, two centuries ago, mining began in Spain.

Maricusa Argüelles was a resistance fighter during Franco’s dictatorship in Spain. Alongside her husband, a mining trade unionist, they fought for the rights of all, workers and the population in general, particularly in the mining districts, where many families were totally dependent on the mine. Maricusa, along with other women, organized clandestine meetings, which they disguised as tea parties, but where in reality they prepared for strikes and demonstrations. They printed leaflets to distribute and mobilize the population.

Among their most notable achievements, they lobbied the company and the state to bring water and electricity to the workers’ village of Barredos. In addition, they took part in the great strike of 1962, which, with the solidarity of the whole region, put the dictatorship to the sword. For many years, the women’s struggle was ignored and silenced. Without them, however, these achievements would not have been possible. Today, with her husband dead and the mines almost closed, Maricusa continues to fight, but now on the side of feminism.