Mexico – Montaña, 2008

The state of Guerrero – southern Mexico – is one of the most remote regions of the country. Its mountainous area, the Montaña, is mainly home to indigenous communities.

Their living conditions are extreme because of their isolation, but also because they live in a climate of terror, caught between the army, paramilitaries, guerrillas and drug traffickers. Since the uprising in neighbouring Chiapas in the 1990s, the government has deployed large military forces in Guerrero, particularly to combat guerrilla movements. The army is responsible for brutally repressing these movements, but in practice the repression is mainly directed against the indigenous civilian population, resulting in forced disappearances, arbitrary arrests, torture, assassinations… For their part, the large – non-indigenous – landowners maintain paramilitary militias to protect and extend their land interests, while the drug traffickers – who also claim control over part of the region – arm their own men. It is also not uncommon for a landowner to be in contact with, or even be part of, a drug cartel.

In such a context of violence, the indigenous populations are nevertheless trying to survive in villages very far from urban centres. Isolation makes access to a certain number of essential rights (health care, education, etc.) extremely complicated. Indigenous people who do not emigrate to the north of the country or to the United States often have no choice but to join the guerrillas or join one of the plantations in the hands of drug traffickers.

Fears that the region will fall under the control of drug traffickers for the long term have increased the repression to which the indigenous people continue to be subjected.

Excerpt from the book DiGNITE, Amnesty International. 2010. Edition Textuel.

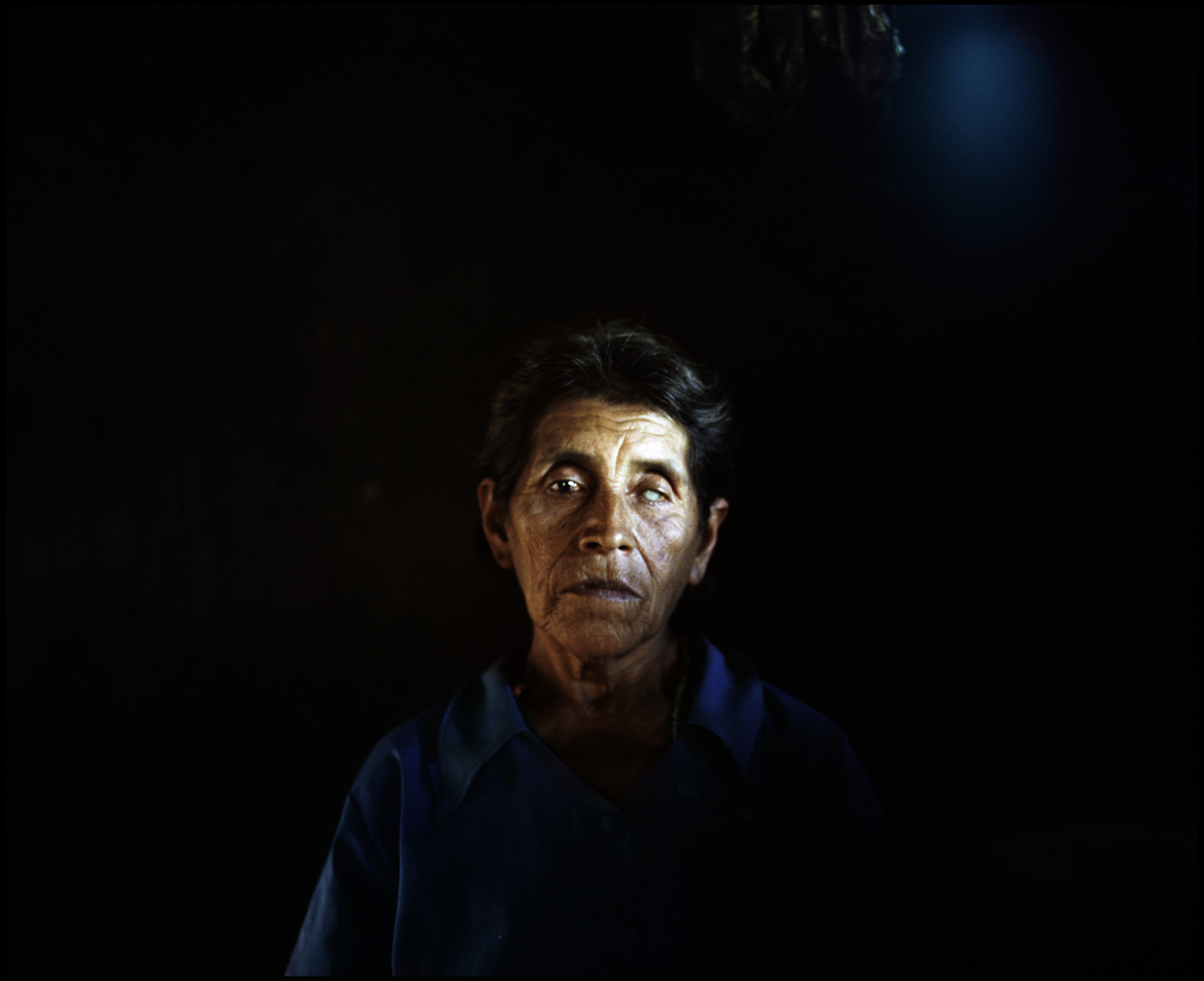

My name is Teresa de Jesus Caterina. I am a Me’phaa. Today I am old, but I am still suffering from the rapes I have suffered. That was in 1993.

My daughter and I went to work in the fields. On the way, we stopped along a stream to catch crabs. Military men arrived and demanded, in Spanish, that they be given water. I replied, in my native language, Me’phaa, “You have hands, use them! ». They then forced us to follow them to their military camp in the mountains. Two women from my community were already there. My daughter and I stayed two days with the soldiers without food or drink, being raped. Then we left the camp and walked.

On the road, we passed my husband, who was drunk and asked them to free us. They replied, “Here we are the chiefs, you are nothing”, before tying him to a tree and hitting him.

We resumed our walk, taking my husband with us; the women were raped at regular intervals, about every four hours. And as I was trying to defend myself, I was tied up with a rope and dragged by the neck. Then we arrived in our village, where they tied me up again and beat my husband.

Then they “offered” my freedom and that of my daughter in exchange for a meal that I had to prepare for them. “If you don’t serve us, if you don’t shut up, we’ll come back for you, now we know where you are! »

They are gone. It’s very hard for me to tell all this. My husband died. He didn’t want me to tell my story for fear of the community’s reaction.

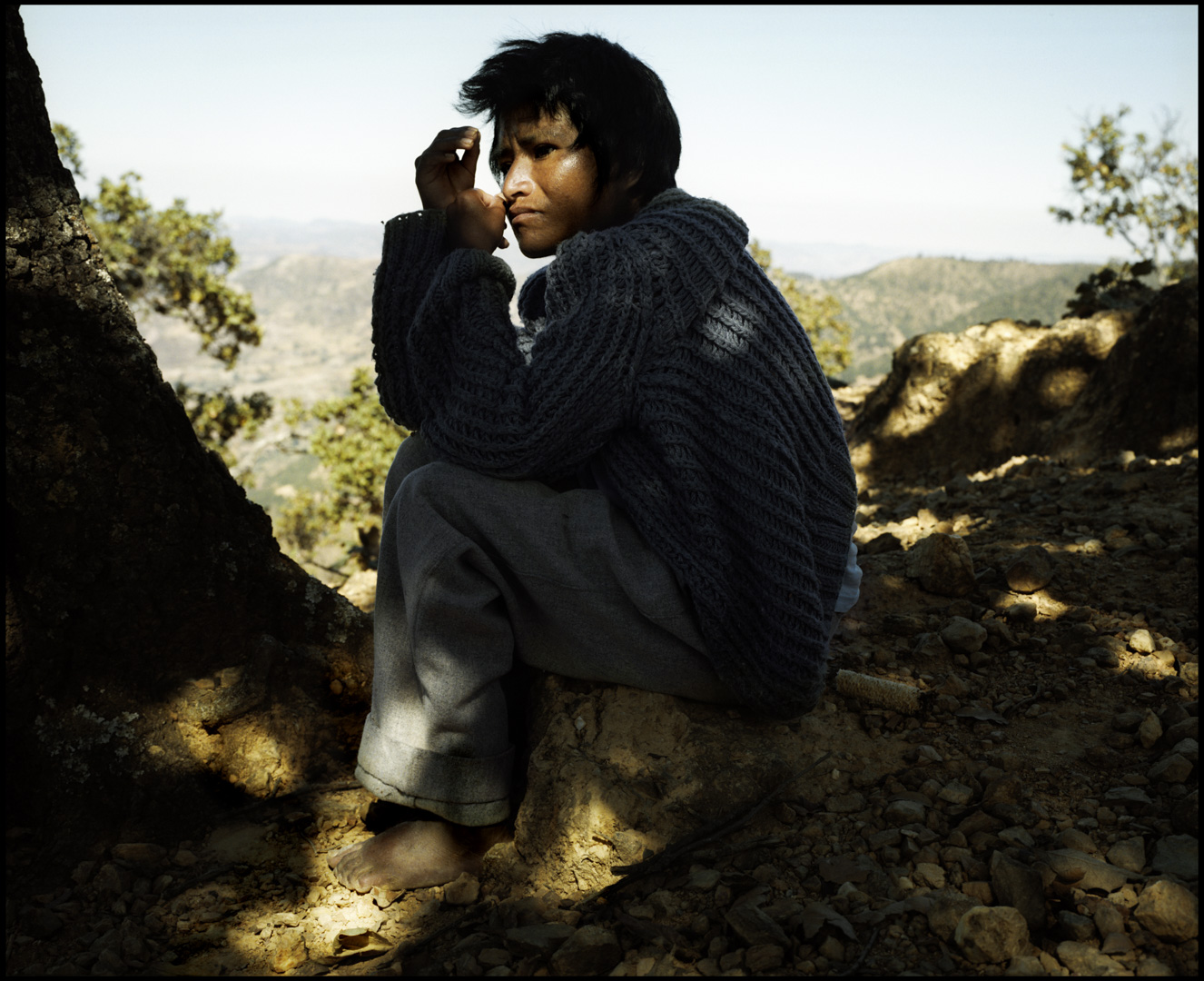

My name is Raul Lucas Lucia, I am from the community of El Charco. In November 2003, soldiers came to my house.

It was 7 o’clock in the morning. I had a coffee in front of my house before I left for work. I heard their rifles click and they immediately wanted to hit me.

“Don’t do this in front of my family,” I told them.We went into the mountains. Then to a quiet corner. They stripped me naked, I found myself in my pants, they made me stand on my knees. They hit me with their rifles.”Where did you hide the weapons? “they asked me. “I didn’t hide anything, I’m unarmed. “They insulted me, humiliated me. Finally, in the afternoon, I was released. There were rumours that I had been part of the guerrillas. Every year I used to go to the site of the so-called El Charco massacre.My brother-in-law was one of eleven people killed by the Mexican army while they were resting after a meeting of the indigenous communities in the school in the village of El Charco on 7 June 1998. As they left, they threatened to kill me and my family if I told what had happened. They were part of the 48th regiment of Cruz Grande.

I denounced the military to the Human Rights Commission, but the justice system did nothing.

On 22 February 2009, the body of Raul Lucas Lucia was found in Ayulta de los Libre, along with that of another human rights defender, Manuel Ponce Rosas. They were respectively president and secretary of the Organisation for the Future of the Mixtecan People (OFPM). Both activists were abducted by armed men who presented themselves as police officers during a public demonstration on 13 February.

My name is Ines Fernandez Ortega, I am Me’phaa, from the community of Tecuani. On 22 March 2002, the military arrived here, at my home. I try not to remember the rape. It’s too hard.

The soldiers arrived by passing behind the house. It was between noon and two o’clock in the afternoon. They greeted me and then three of them stopped me and took me to the kitchen. I had some meat that was drying. They took it and said, “Where did you steal this meat from? “I told them, “It was my cow. “One of them pointed his gun at me. I said, “You have to stop stealing”. Then they grabbed me and my children went to their grandparents’ house 250 metres away. I was raped by the three soldiers. Nine others were standing guard around the kitchen. Everything seemed very organised.

Since I denounced this crime, the community looks at me differently. So does my husband. He has become violent. I no longer trust him. He refuses to let me tell my story. Every day I argue with him and he keeps telling me, “You were touched by the soldiers, you just have to go with them! “He insults me in front of our five children, he kicks me in the stomach, hits me in the face, pulls my hair. So I run away and hide in the mountains, standing behind a tree. I wish I could dream, but every night, in my nightmares, I relive the rape.

Today, I am always afraid: afraid for my children, afraid that something will happen to them. I am afraid to go out and be raped again. The government and the local authorities never helped me find the men who did this to me. In any case, they never did anything for us, for the indigenous people. My brother was murdered in February 2008. He was kidnapped and tortured by paramilitaries, so that I would keep quiet and withdraw my complaints.