Dark Souvenirs, 2023

2004. Poland. I was photographing the Auschwitz concentration and extermination camp where more than a million people, mostly Jews, were killed by the Nazis. It was winter. I was alone walking among the barracks. The presence of death was everywhere. To warm up, I just had to cross the road to a fast food restaurant. There you could have a hot coffee and a good hamburger. Next door there was also a gourmet restaurant, the best in Oswiecim, and a hotel under construction. The mayor of the town wanted to make the camp a tourist destination. Souvenirs started to be sold there. In one of the shops, I bought fridge magnets with a photo of the camp entrance and the terrible phrase “Arbeit macht frei”: an object that struck me as banal and whose utilitarian purpose seemed to me to be defamatory and made me wonder about our society’s relationship with memory.

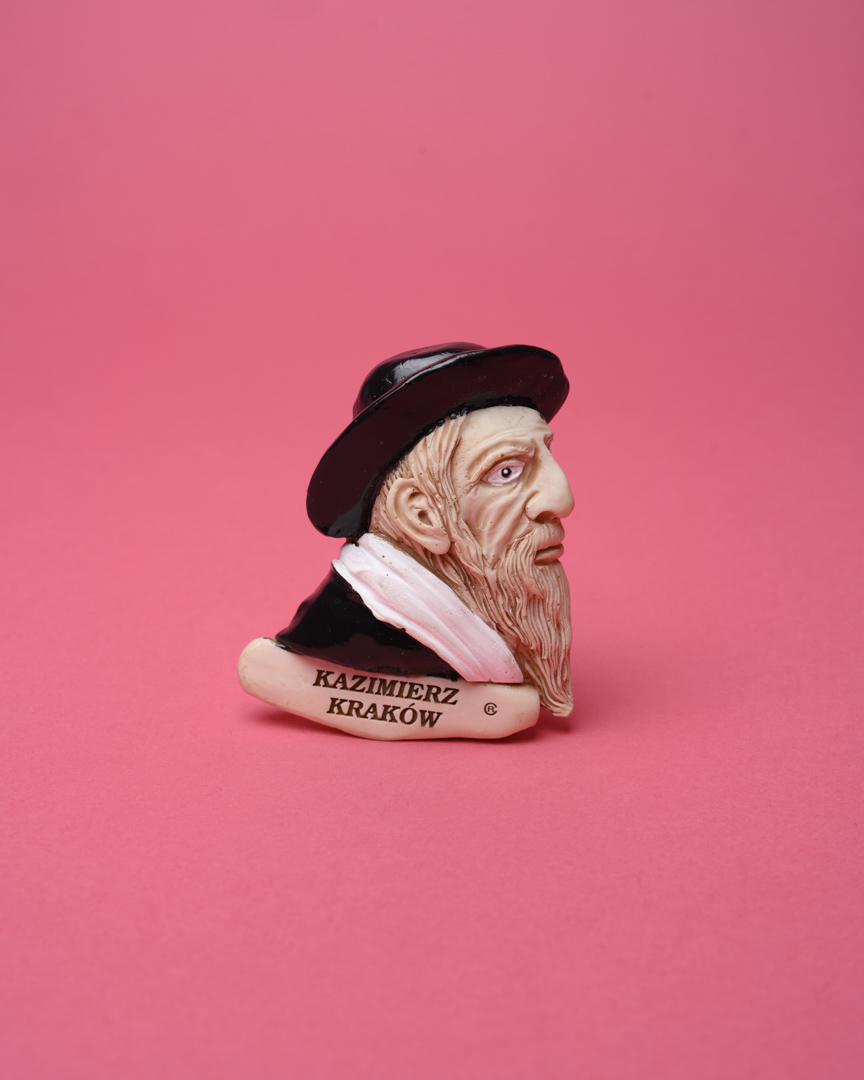

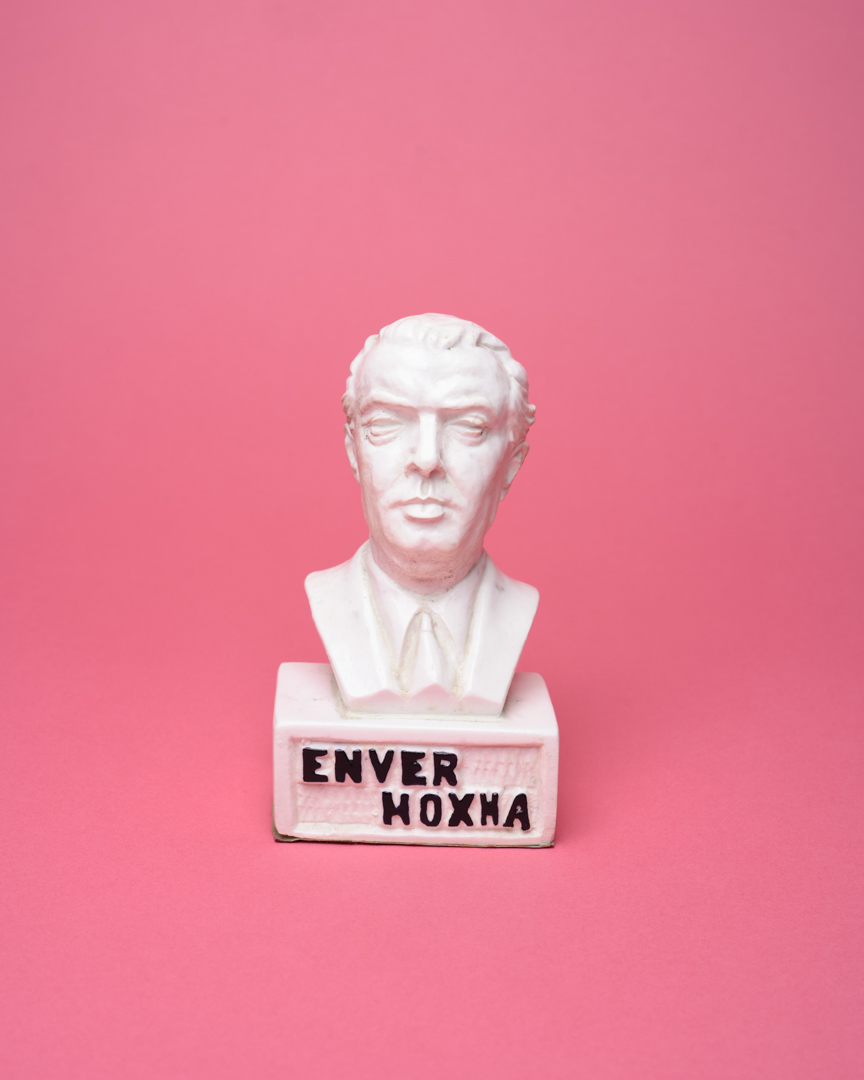

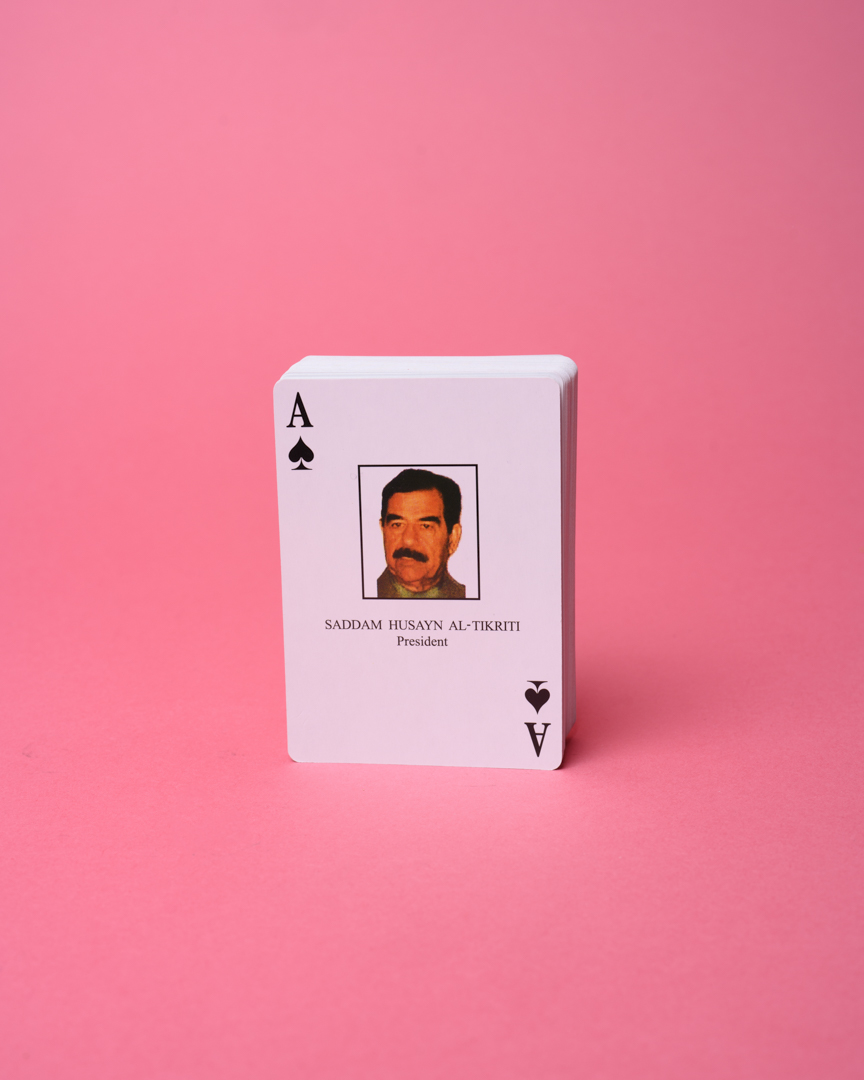

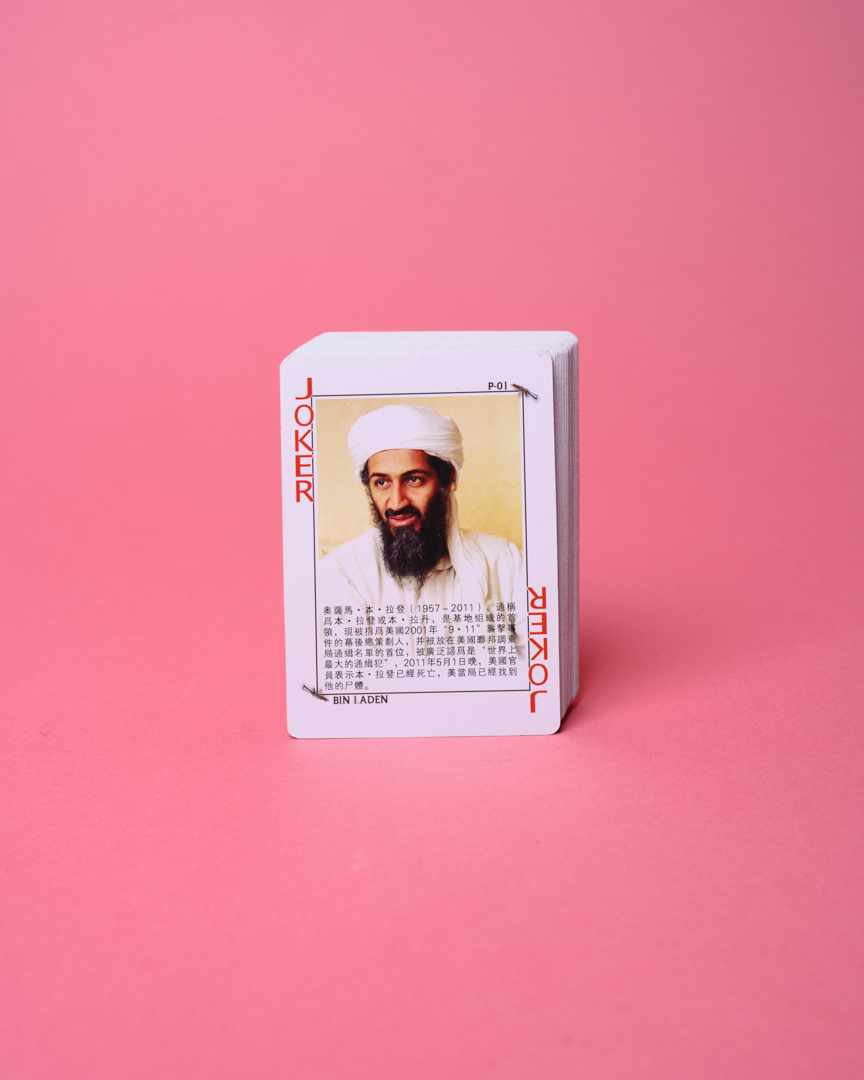

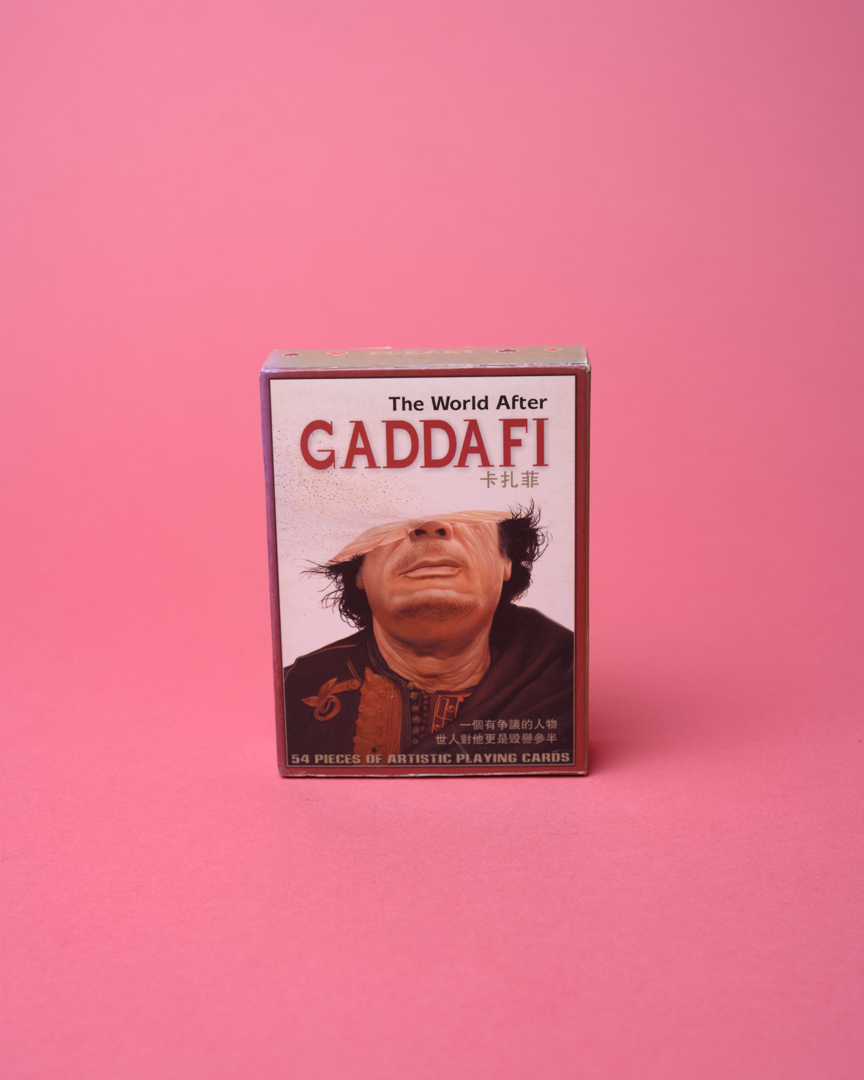

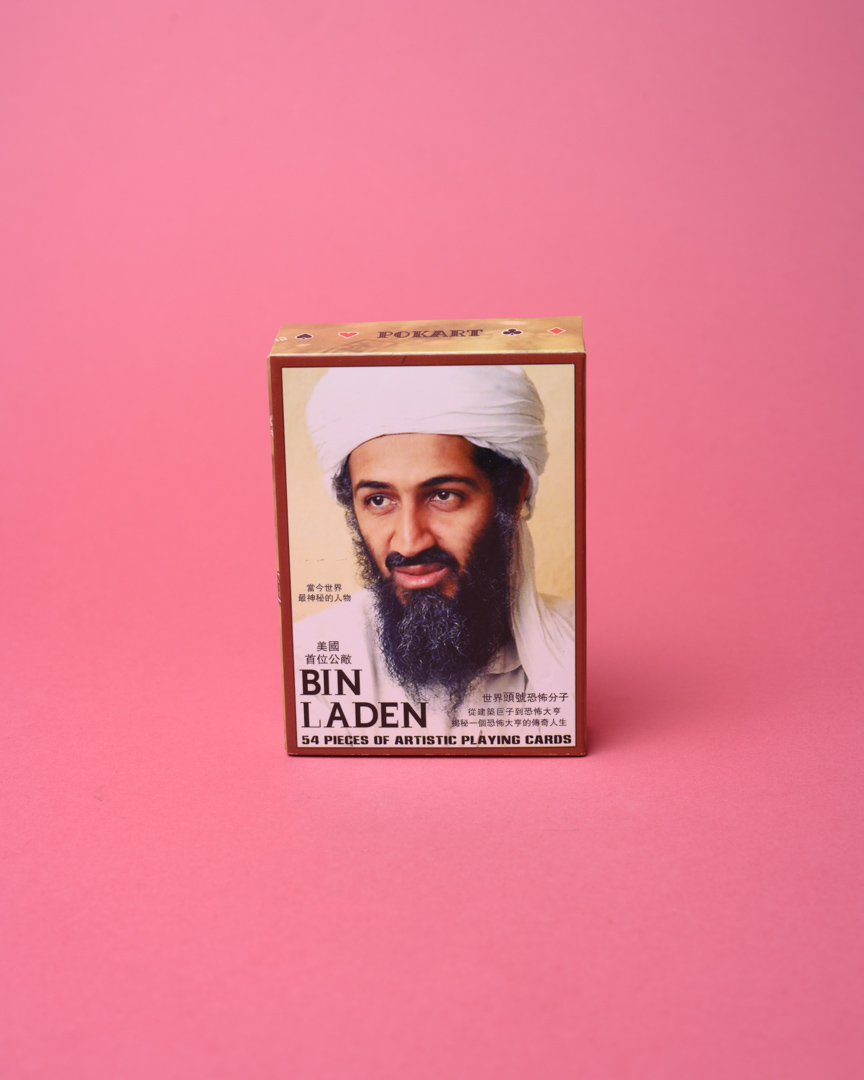

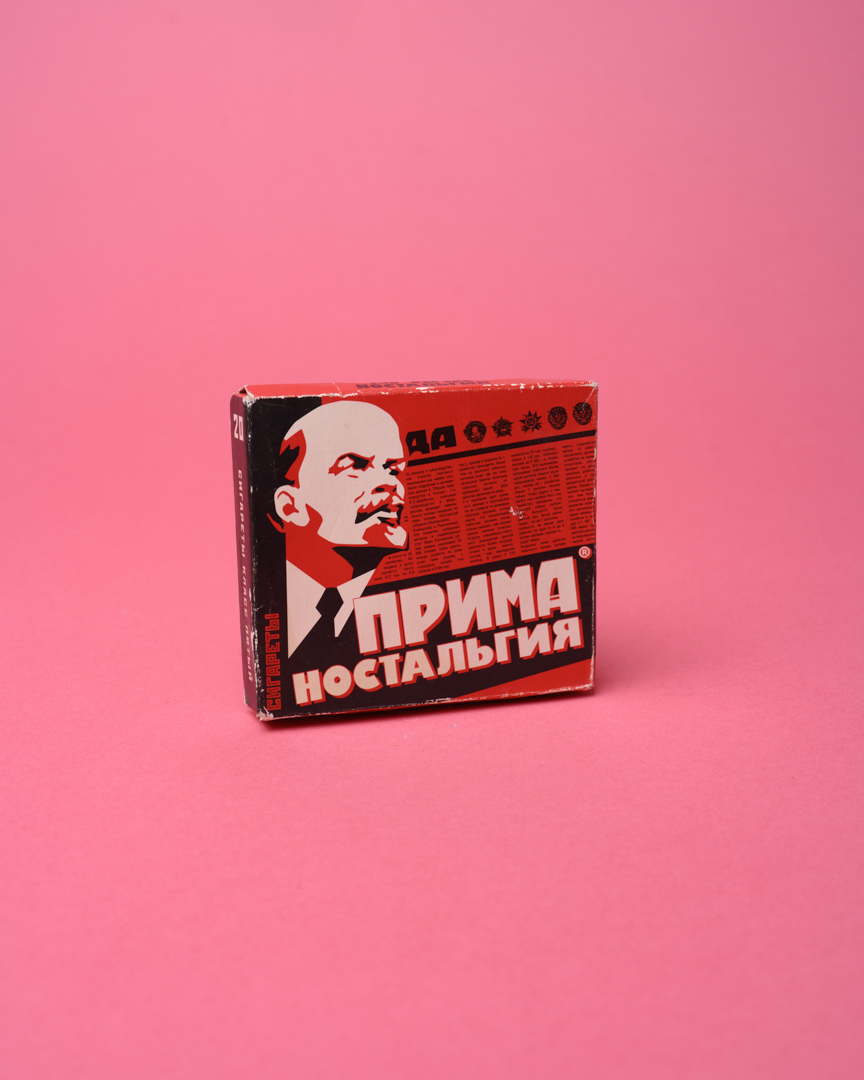

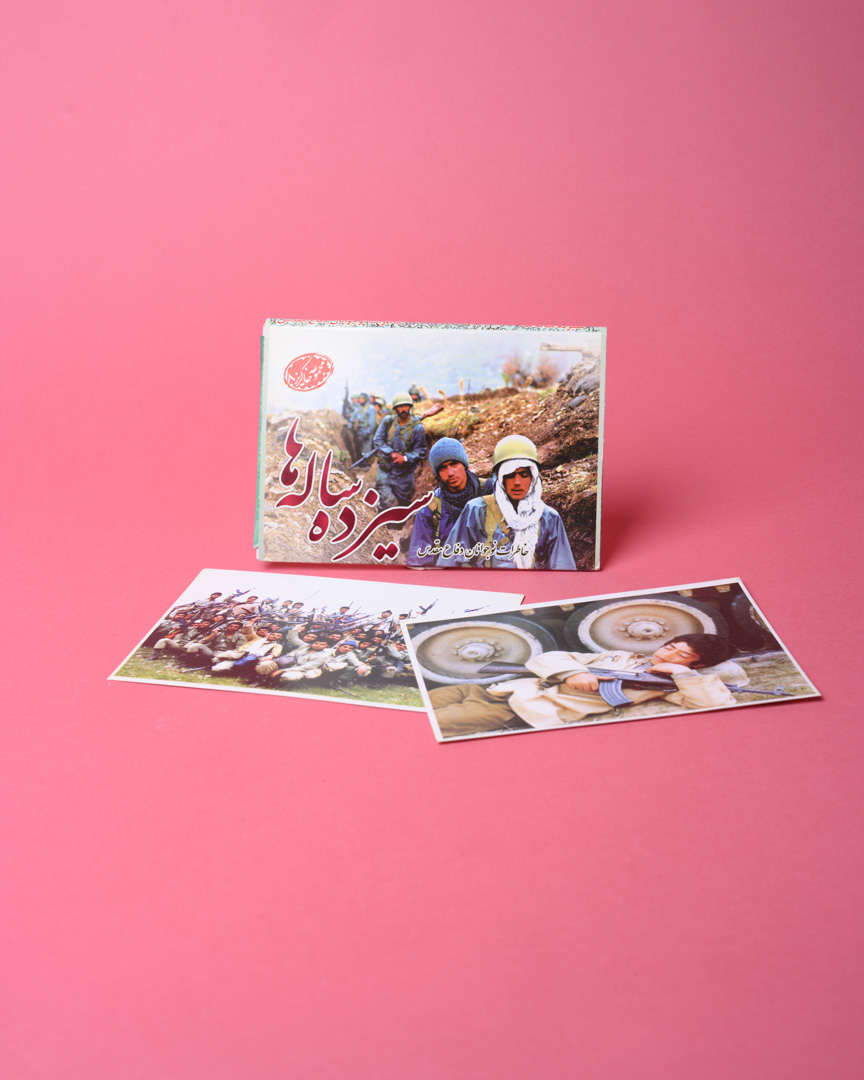

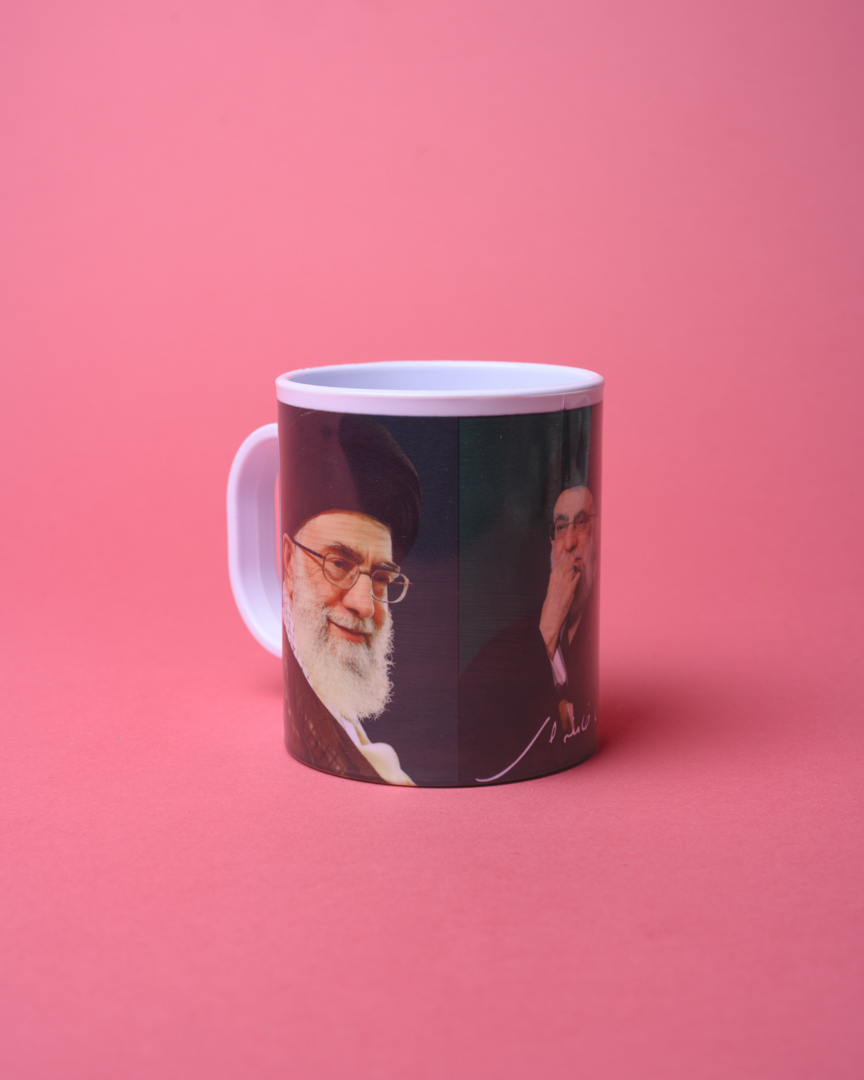

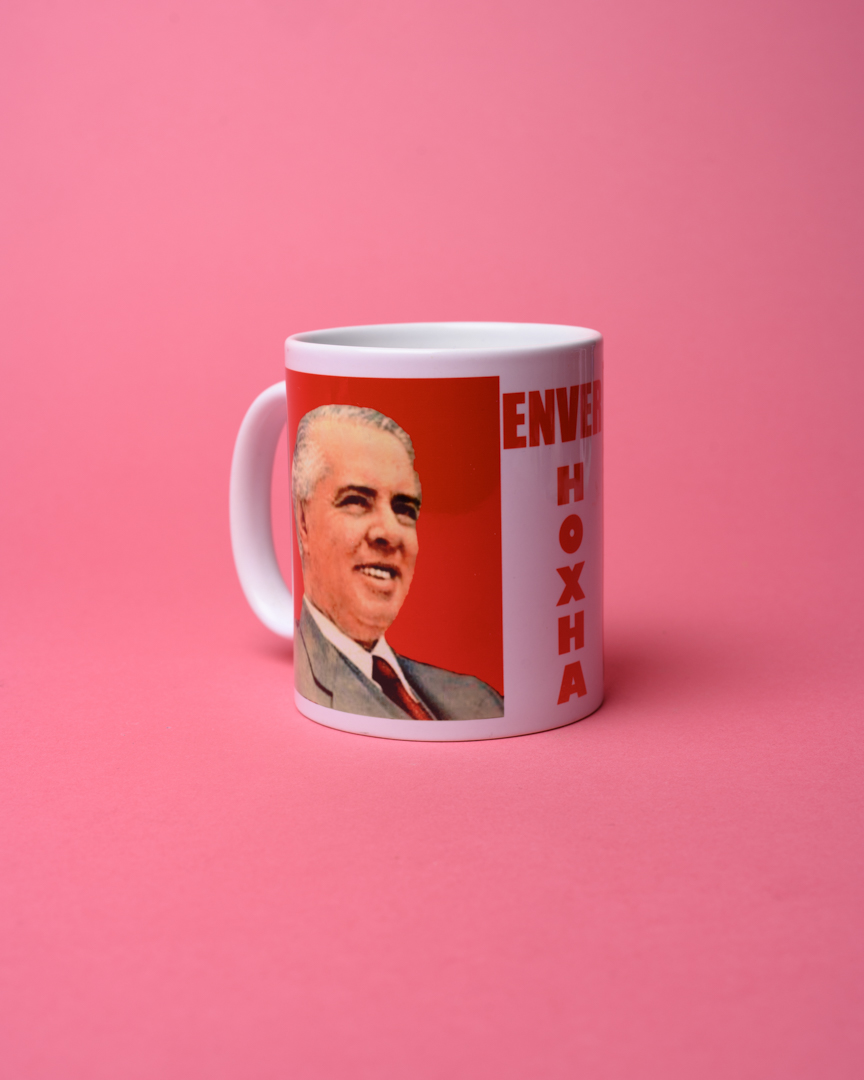

Very quickly, as I was travelling for assignments or personal projects, I began to systematically look for these souvenirs of trips: Chernobyl and its snowball of the catastrophe; Putin declined in several forms through time; Bin Laden after 9/11.

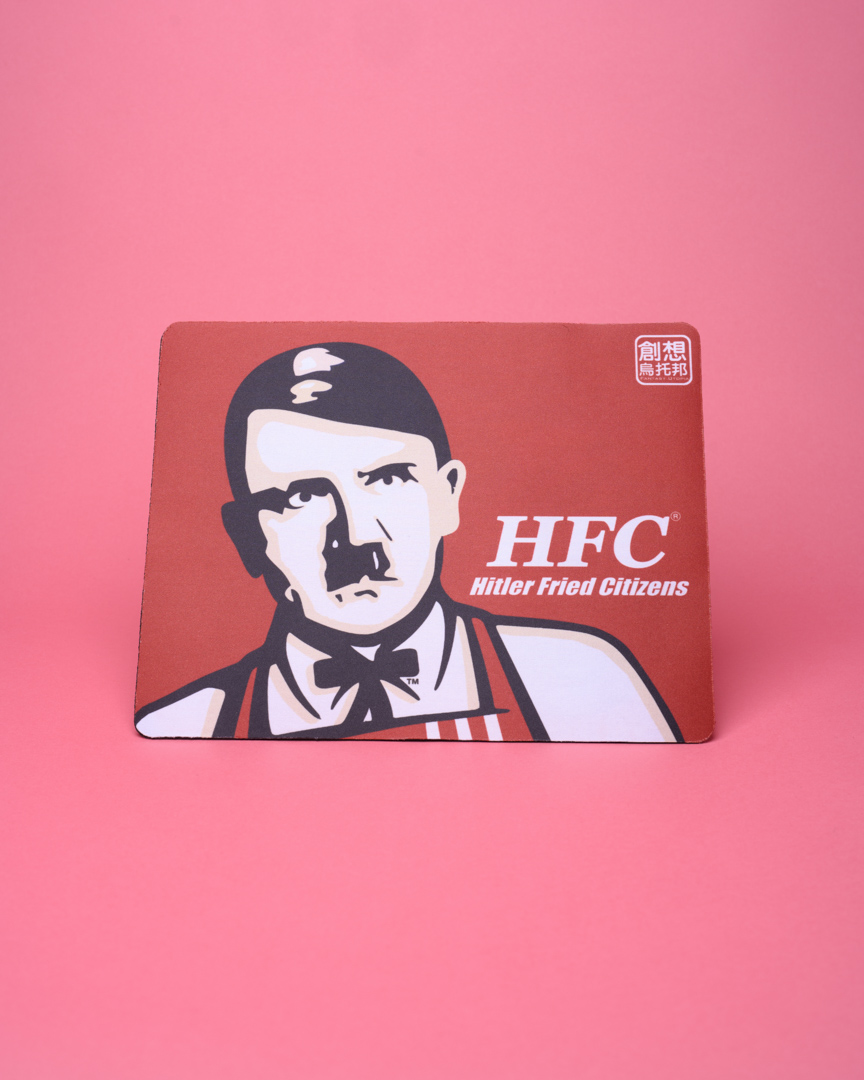

These objects have lost their memorial function, objects that were meant to remember the pain of the past, like those that could be sold during the First World War.

They have become commercial objects, reducing the tragedies of history to a blink of an eye, a pretext on which to sell.

They trample on the memory of the victims who suffered wars, the Shoah, police repression, the reduction of freedoms.

And when they are not directly involved in propaganda, they turn the drama into a sneer.