A bird in the hand worth two in the bush, 2009

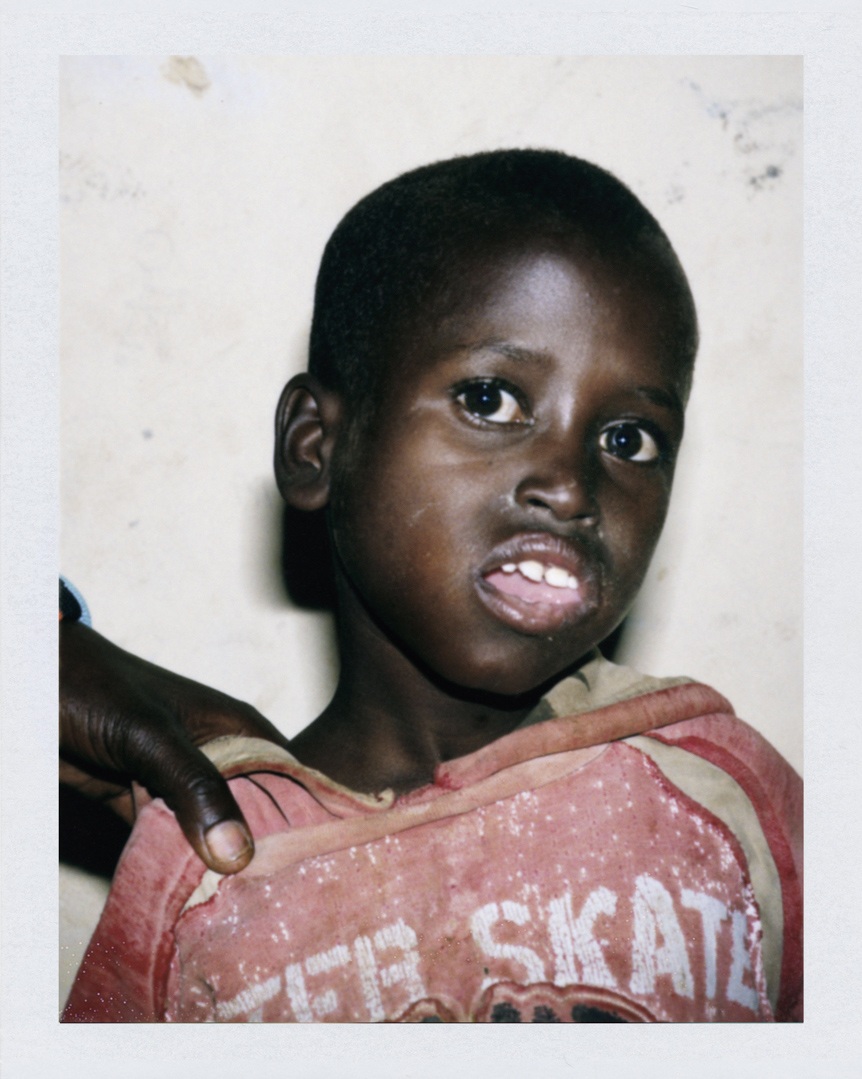

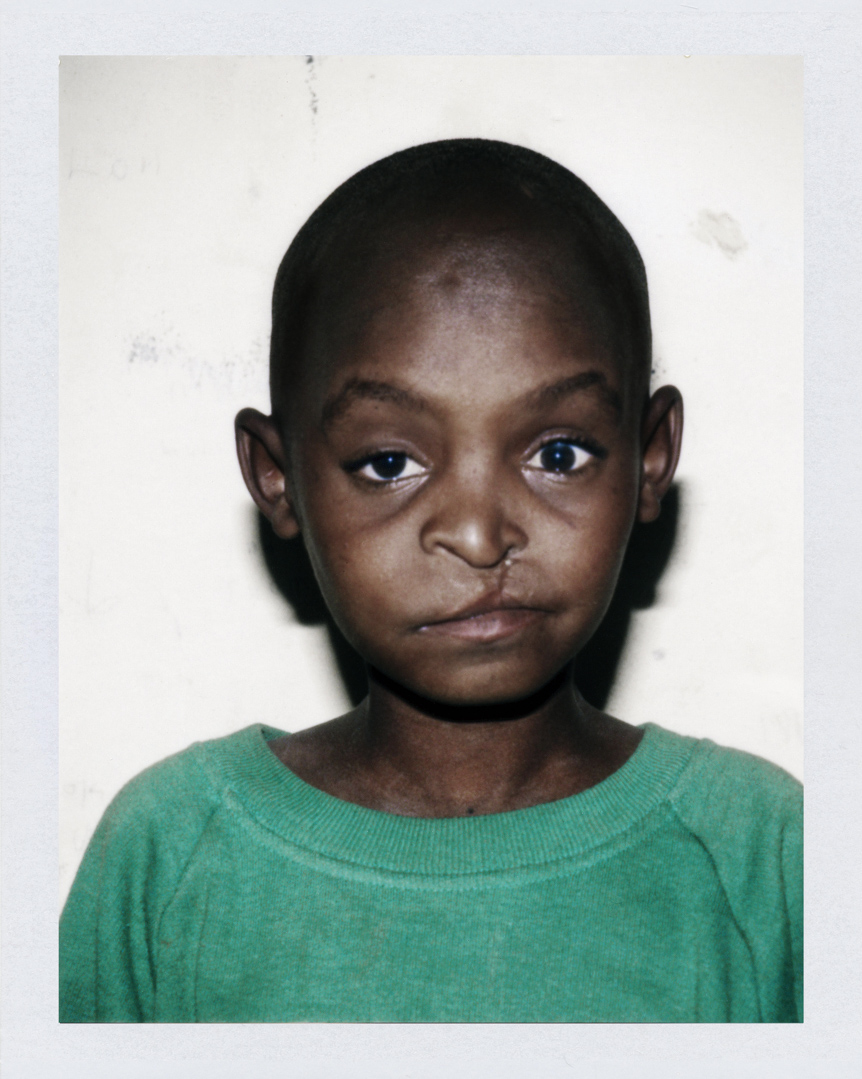

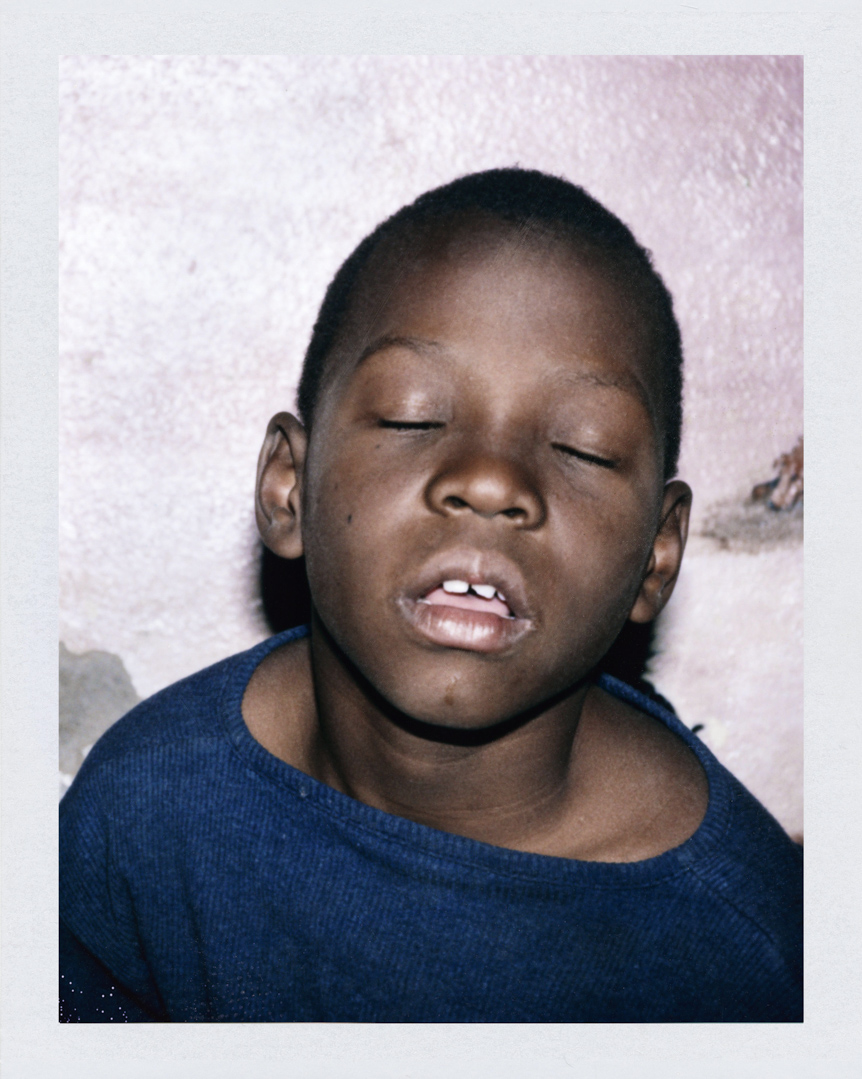

In Africa – and mainly in traditional communities – a disabled child has very little chance of survival. A malformation or mental deficiency is a sign that something is breaking. The matrons of certain ethnic groups in West Africa make the disabled child disappear at birth, these “Ngoki” (incomplete) babies do not die completely as they are said to have “returned” to be reborn later.

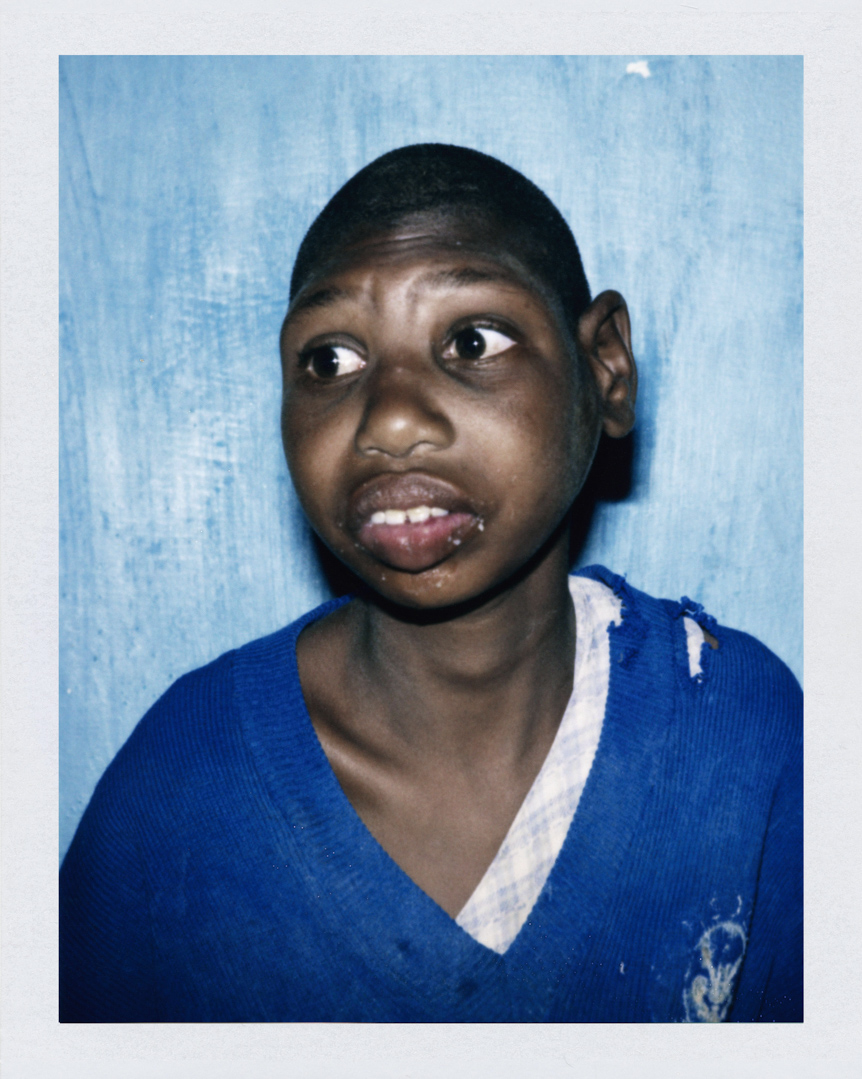

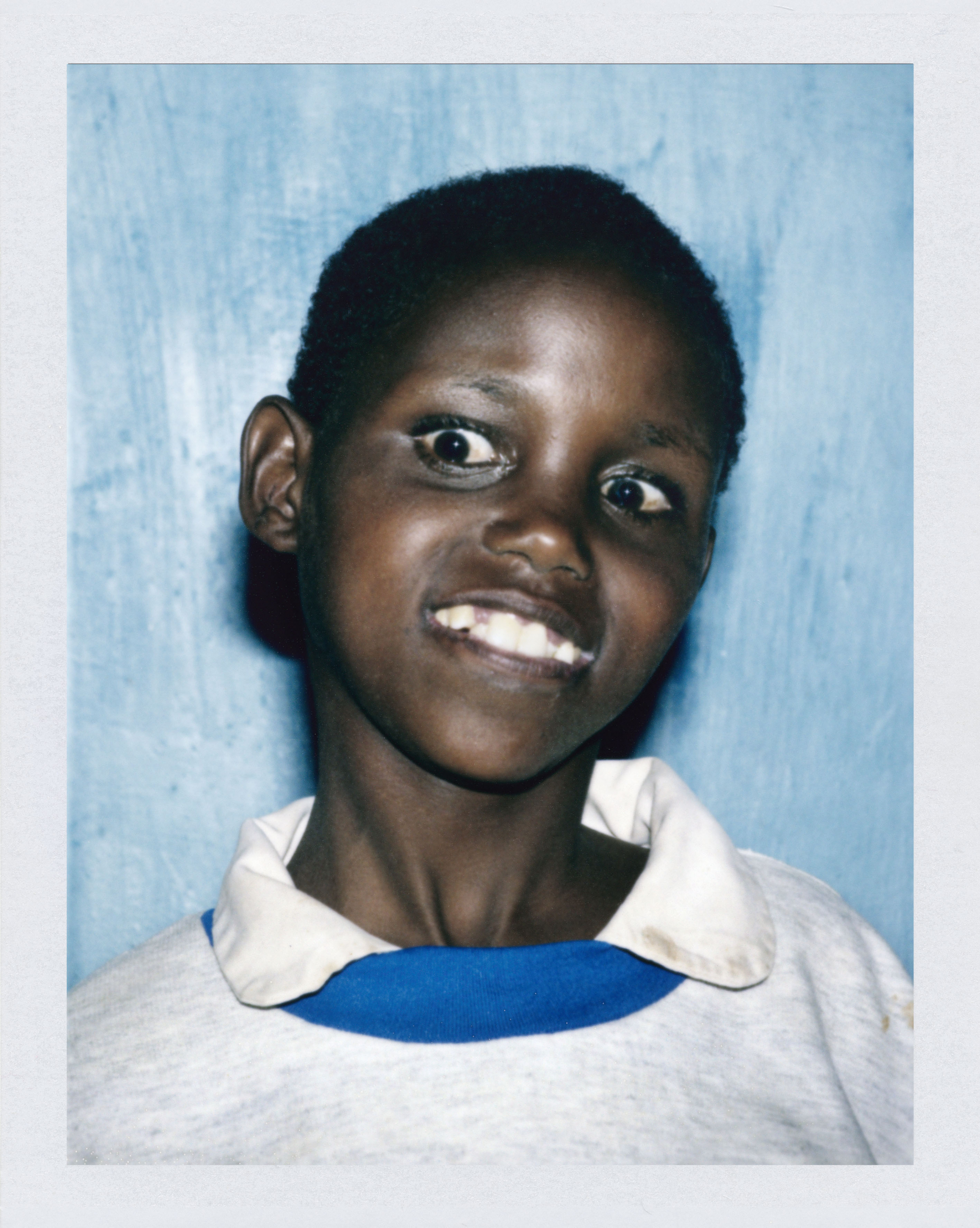

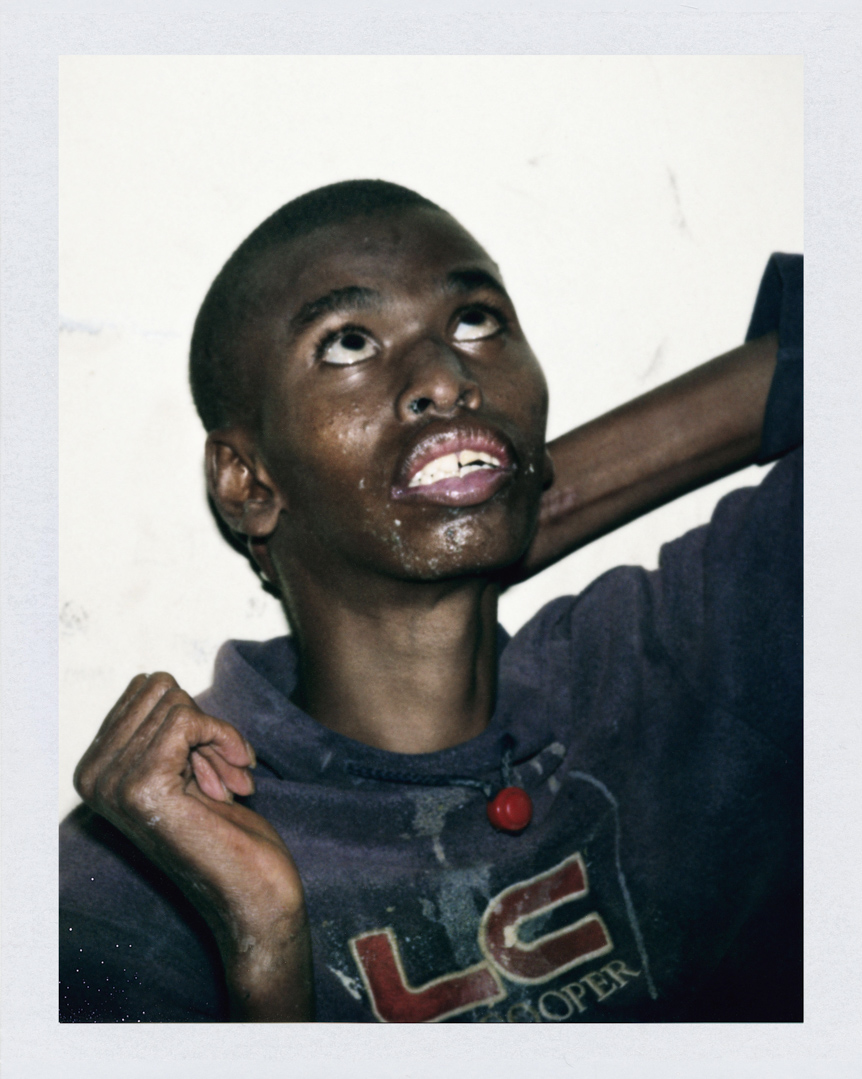

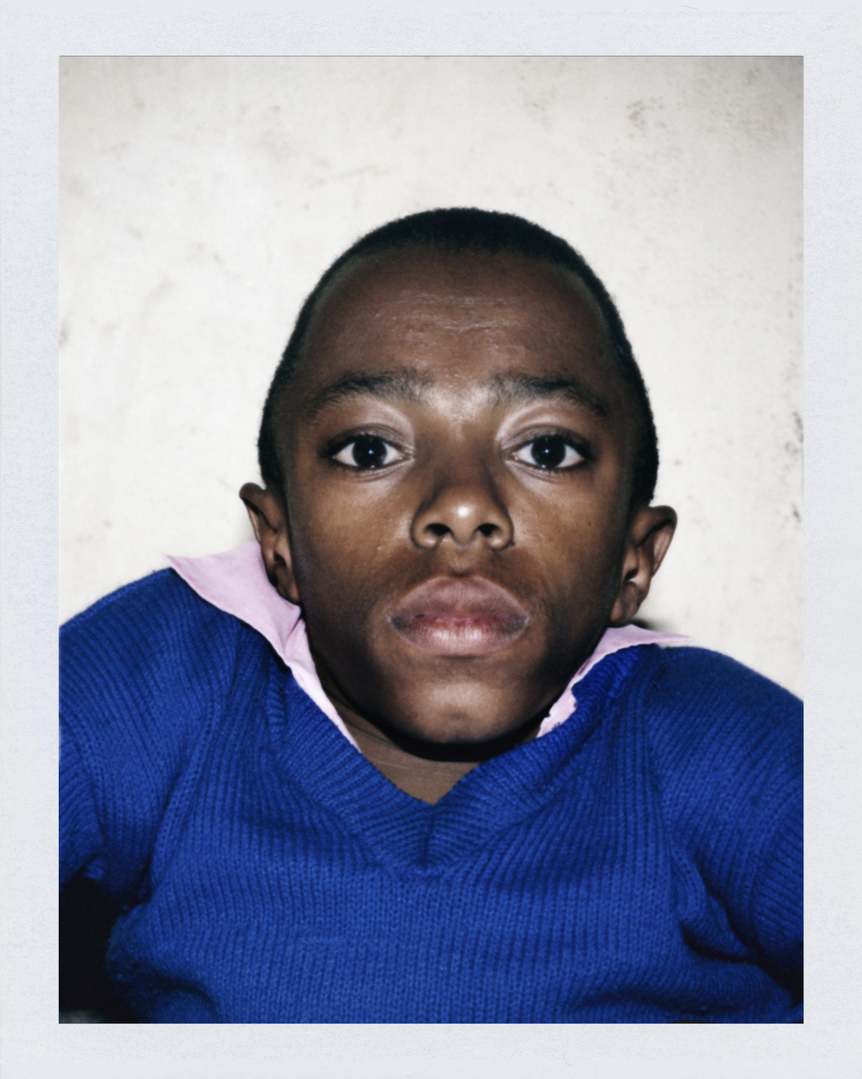

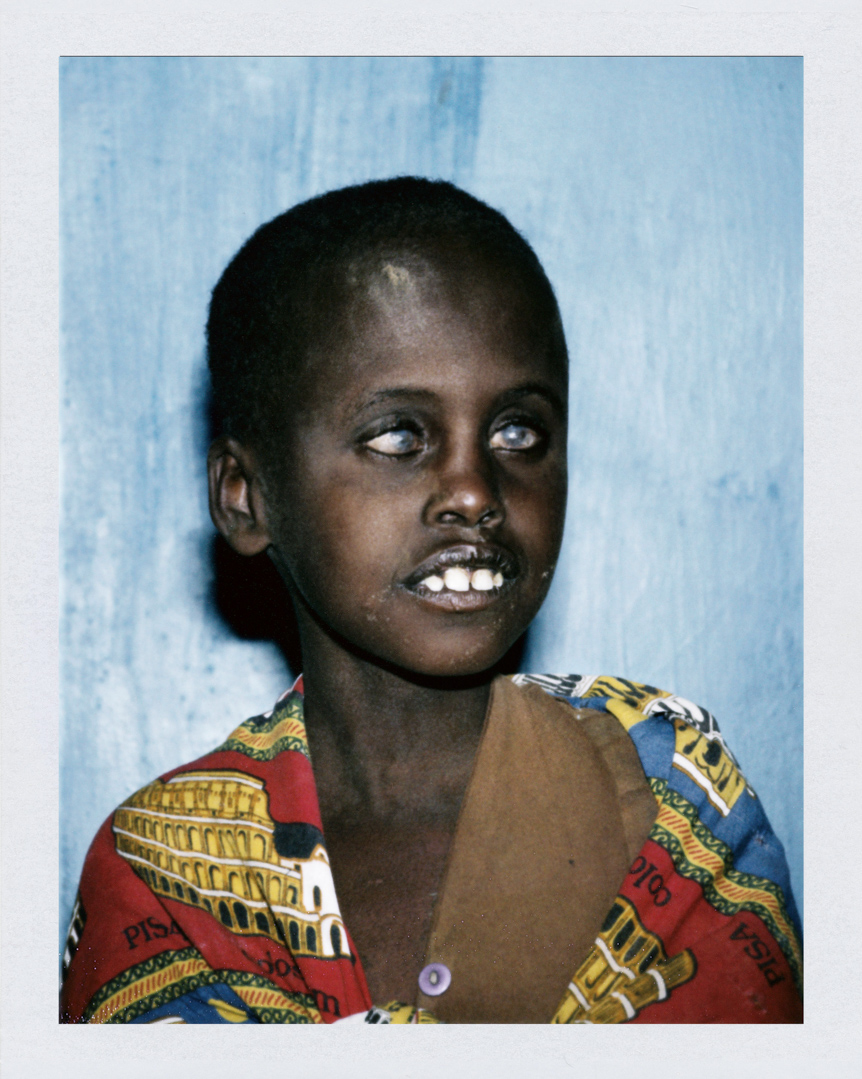

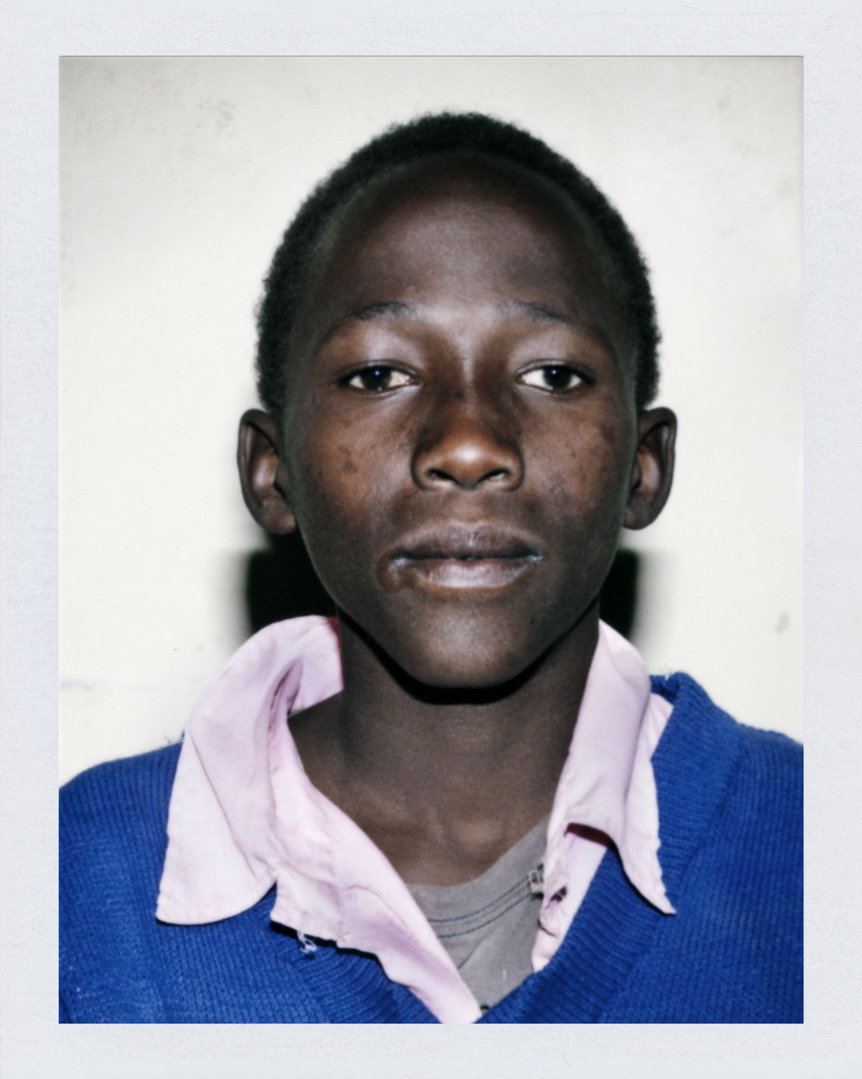

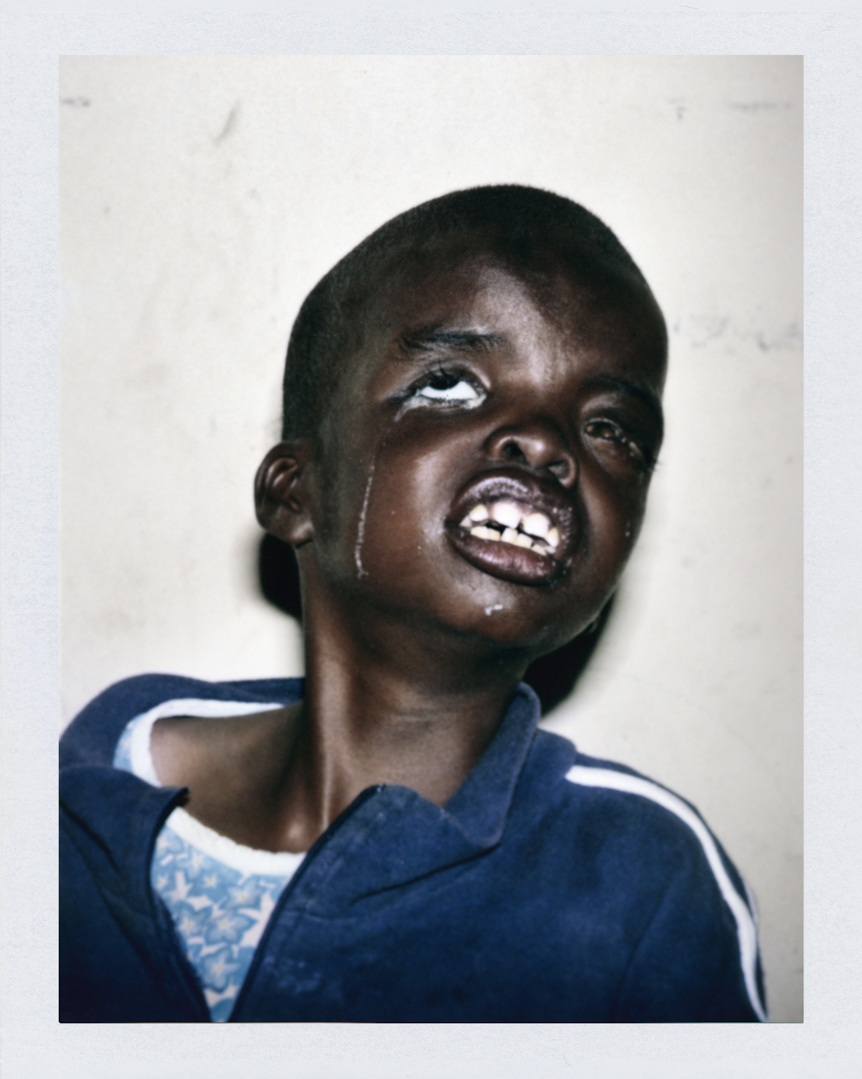

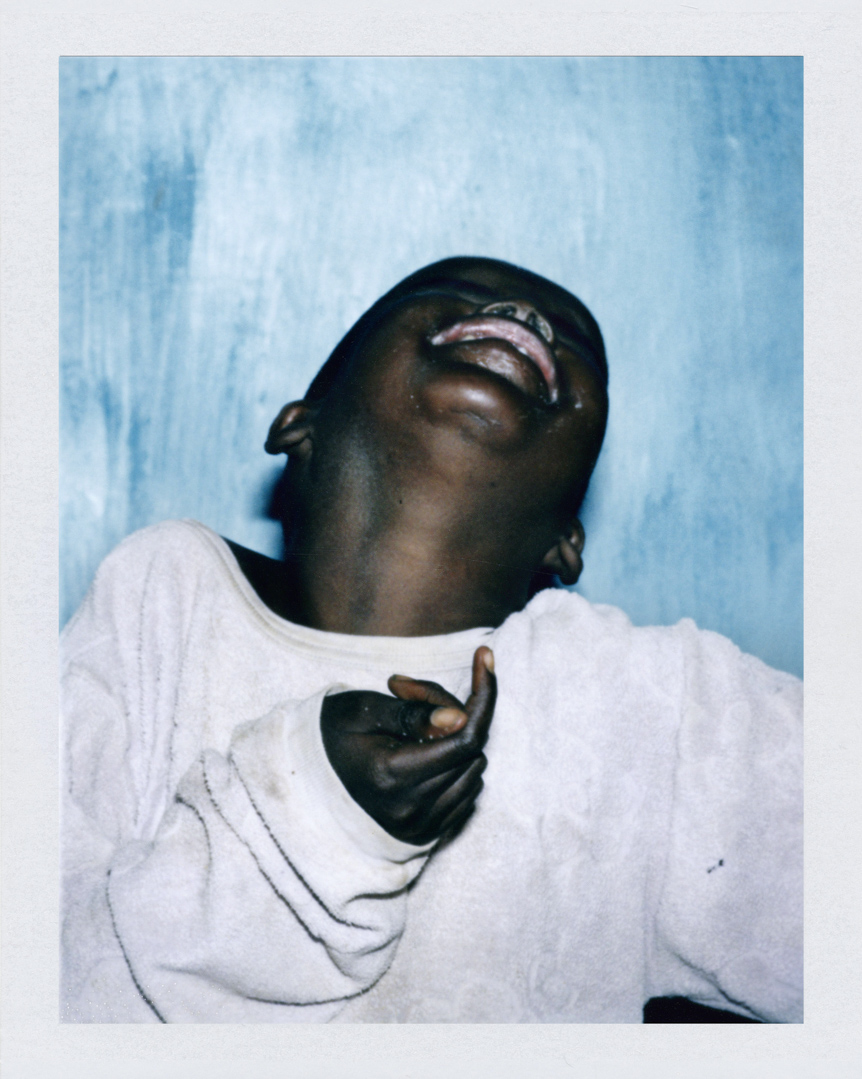

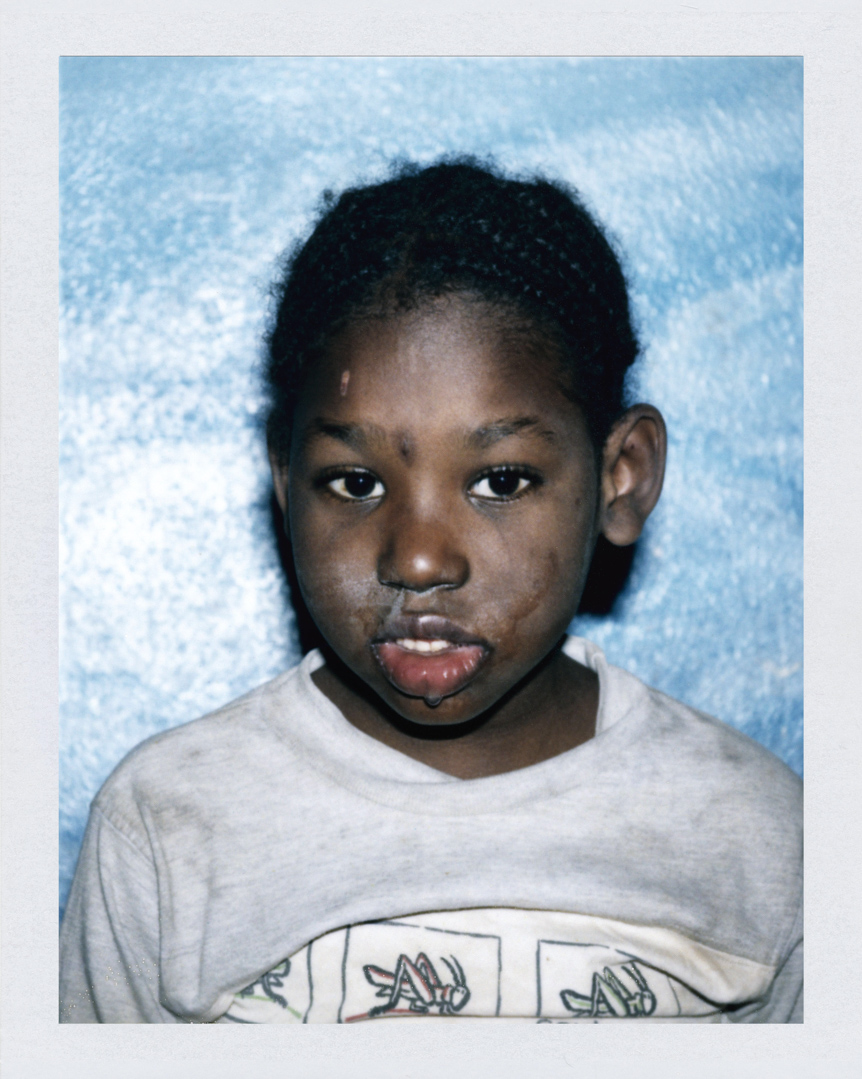

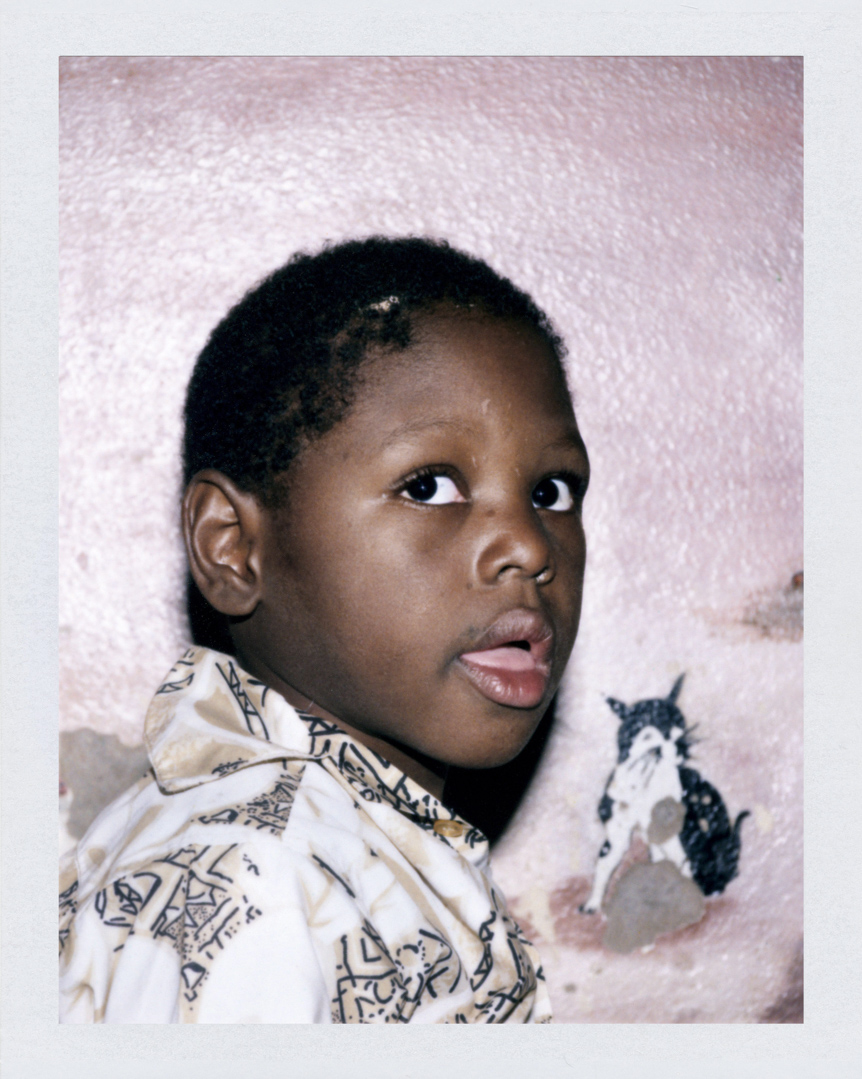

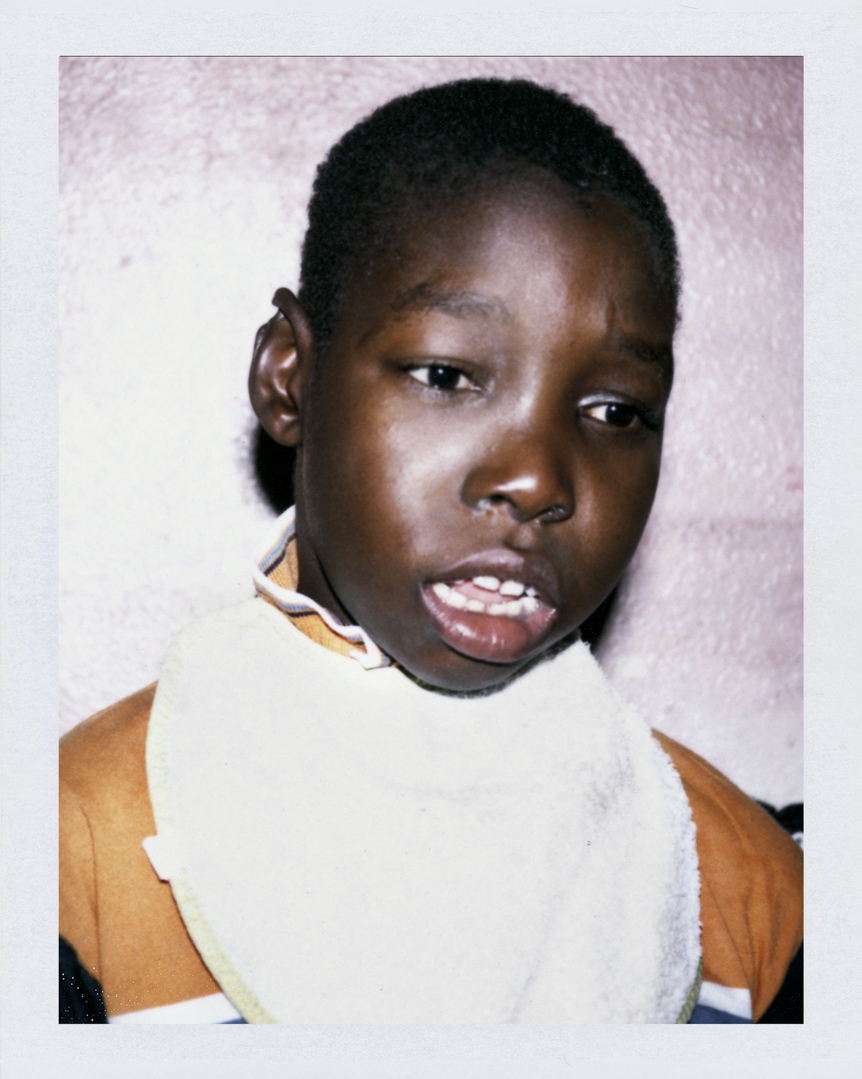

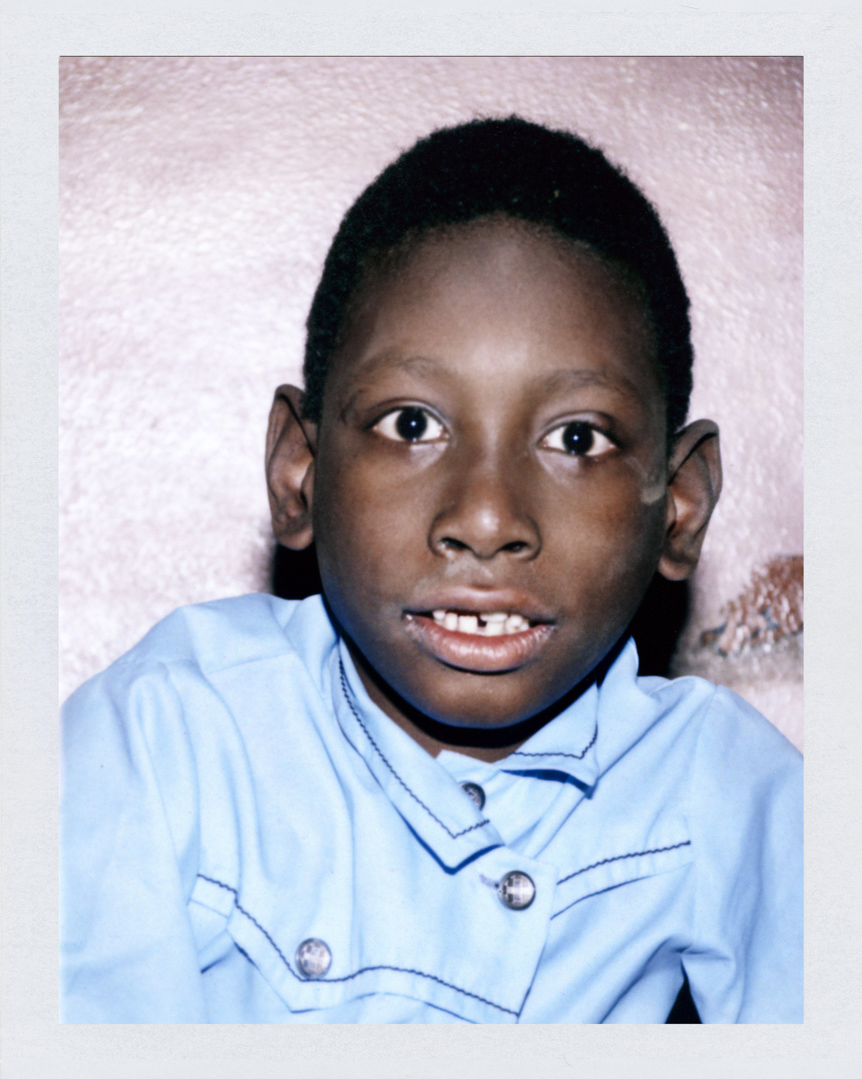

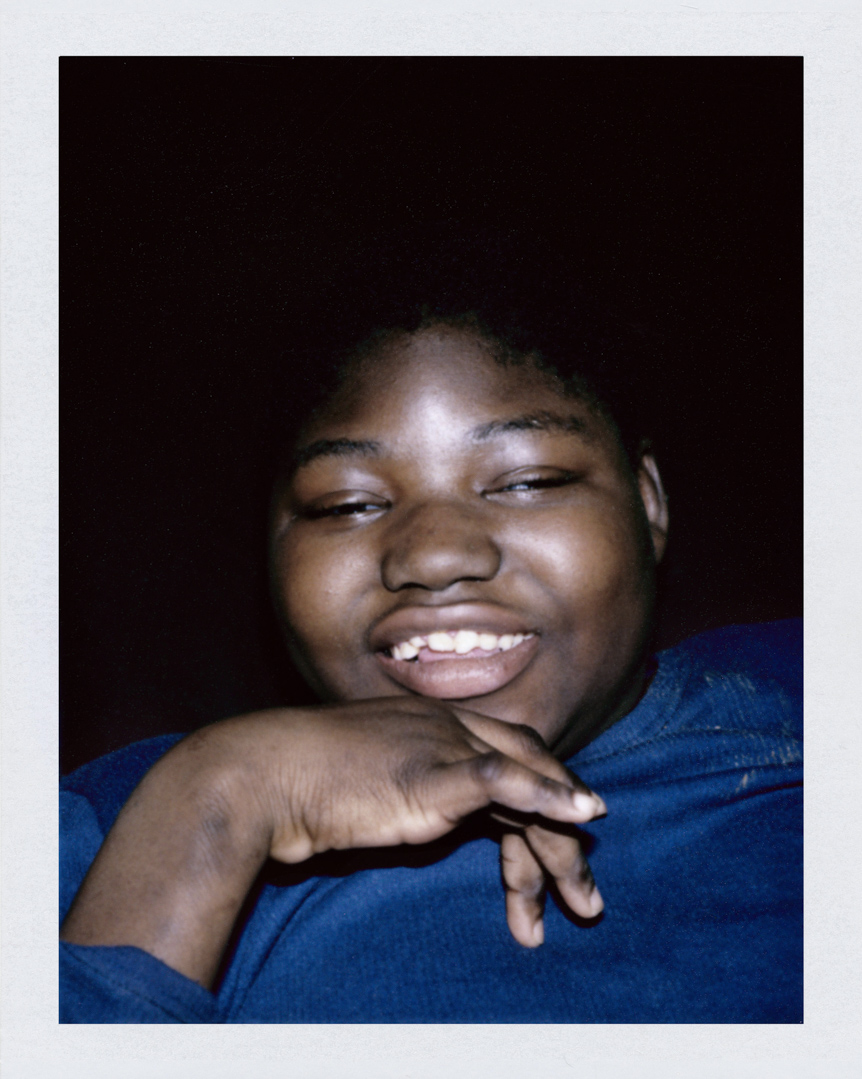

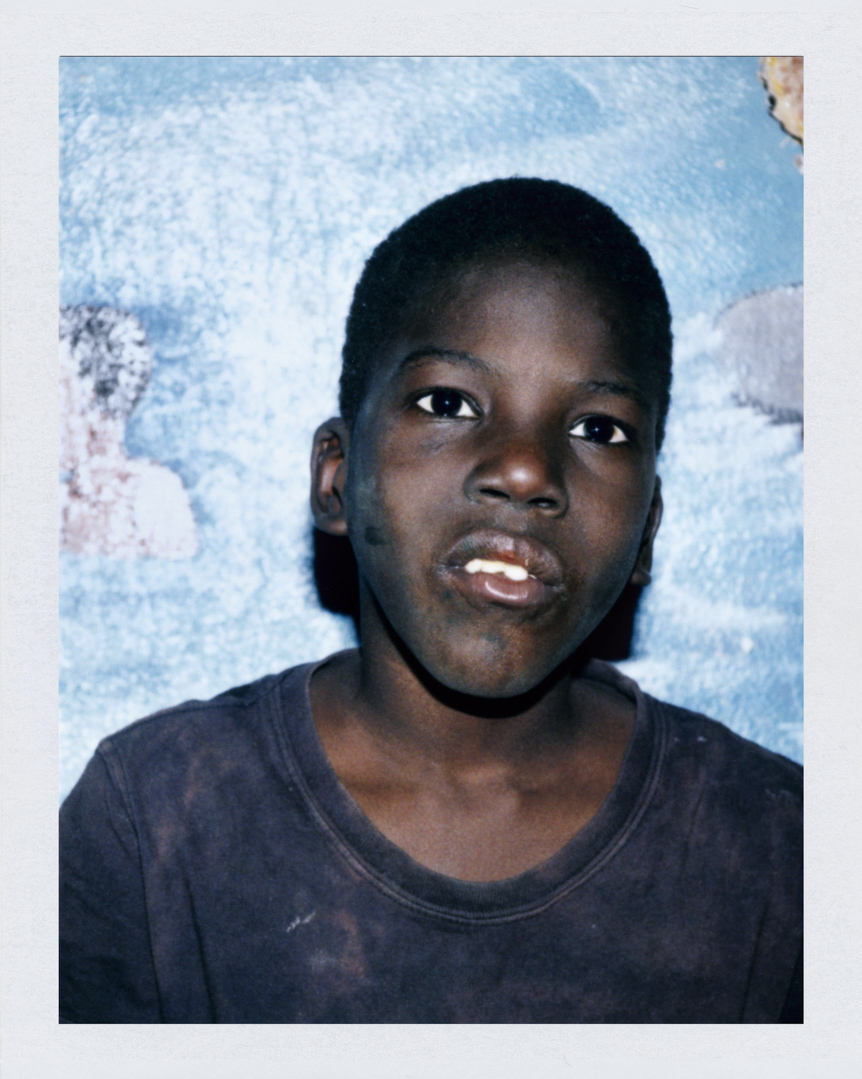

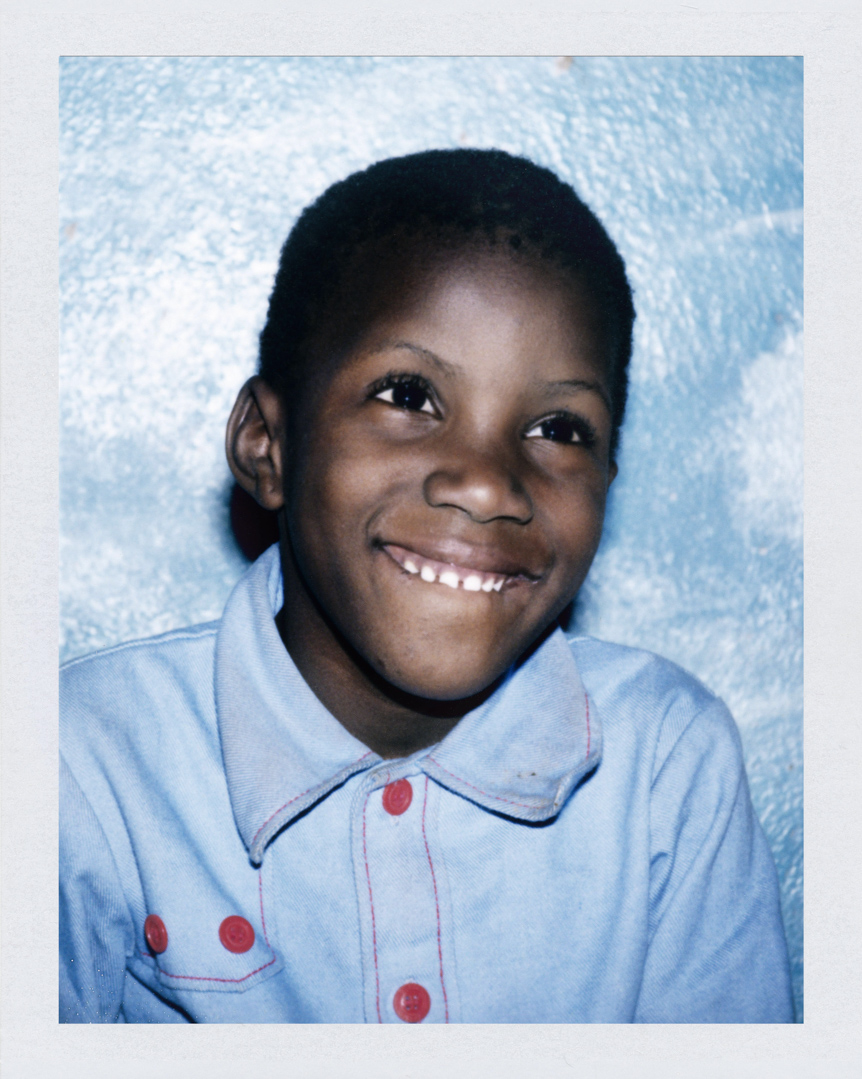

For two years, Malik Nejmi has been documenting the lives of children who have been excluded from their families because they were born different. The issue of disability, which is closely linked to the taboo, was extended to the very specific case of the twins of Mananjary in Madagascar, because this was a concrete expression of a view of diversity (the fact of living together) which excluded any notion of guilt about the real suffering of the children.

It is the complexity of this report, this distance that one must have to admit these abandonments, to assimilate various interpretations of disability or gemellity into specific cultural systems. Any story about these taboos originates in local mythologies and generally blames the mothers who carried this spirit in their wombs. In Madagascar, the Fady Kambana (taboo of twins) has been told for centuries. In Kenya, one only has to observe the Morans (young Maasai warriors) spending whole hours putting on make-up and adorning themselves with beauty attributes, to understand that disability cannot exist in the Maasai language.

In Bamako, you have to take the time to listen to these stories, that a disabled child belongs to the community of the Djinns (evil spirits). The project entitled “African Shade: When taboos make orphans” started at the Bamako Nursery in Mali in 2008, where some fifteen disabled orphans taken in by the Léo association reside. Malik Nejmi then went to Northern Kenya, in a Samburu environment, to raise the issue of disability management in a traditional nomadic environment, at the Sherp centre in Mararal. Then, Madagascar in early 2009, where it is difficult to grasp the rationality of the taboo. All children are survivors, dying the day they were born.

“There, in front of the camera, I tried to chronicle their daily life with the staff who care for them and love them. This work should one day take me to Algeria to deal with the case of the so-called “illegitimate” children in a Muslim context, and then I will no doubt write in the form of notes, how in my work I have this intuition to open my wounds to enlarge my family. »

A series of interviews entitled “The Humanitarian Line”, which gives a voice to those who have committed to saving these children (associations, doctors, volunteers, teachers), accompanies this project.