White Islands of the South Sea, 2018

In the 19th century, miners used small canaries to ensure their safety. Sensitive to toxic gas fumes undetectable to humans, the bird served as a reference probe: when it fainted or died, the miners evacuated the mine, aware that an explosion was imminent.

The Republic of Kiribati is the canary of the 21st century.

Kiribati is made up of three archipelagos lost in the middle of the South Pacific, both on the equator and on the date line. Its closest neighbours are Australia (8 hours by plane) and Los Angeles (11 hours by plane).

Today this small country of about 100,000 inhabitants is the scene of a drama that concerns us all: with global warming and rising waters, it is sinking. In twenty years’ time, its atolls will no longer be there. The canary is dying and we miners are unaware of it.

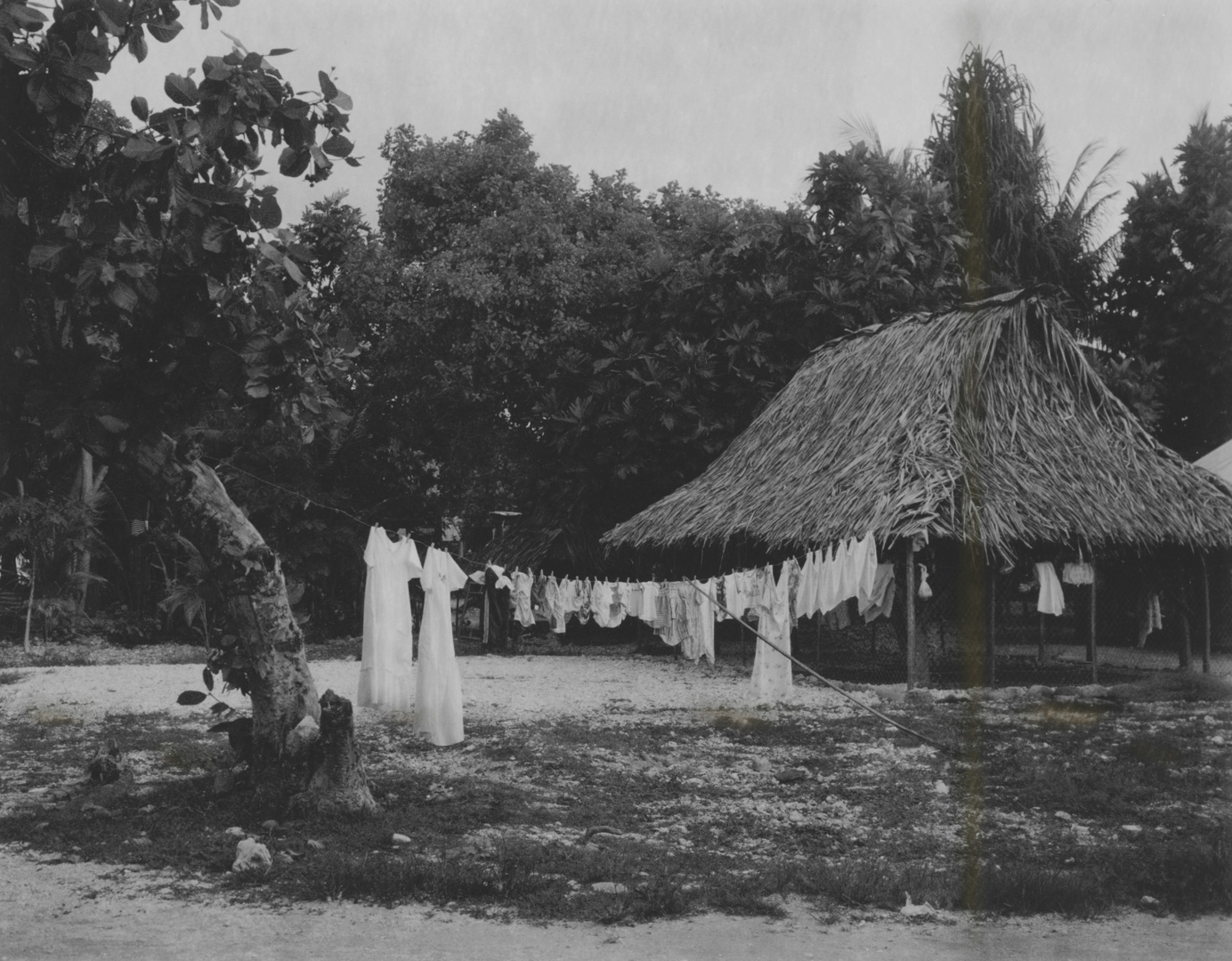

In Kiribati, the shock of the ecological threat contrasts with the paradisiacal aspect of the landscape and the simple way of life of its inhabitants. Ironically, this little-known country, whose environmental footprint is almost non-existent, is among the first victims of climate change.

Anate Tong, President of the Republic of Kiribati, bought land in Fiji in 2014 to save its population. The exodus will begin soon, but the deep ties that bind a people to its territory cannot be transported.

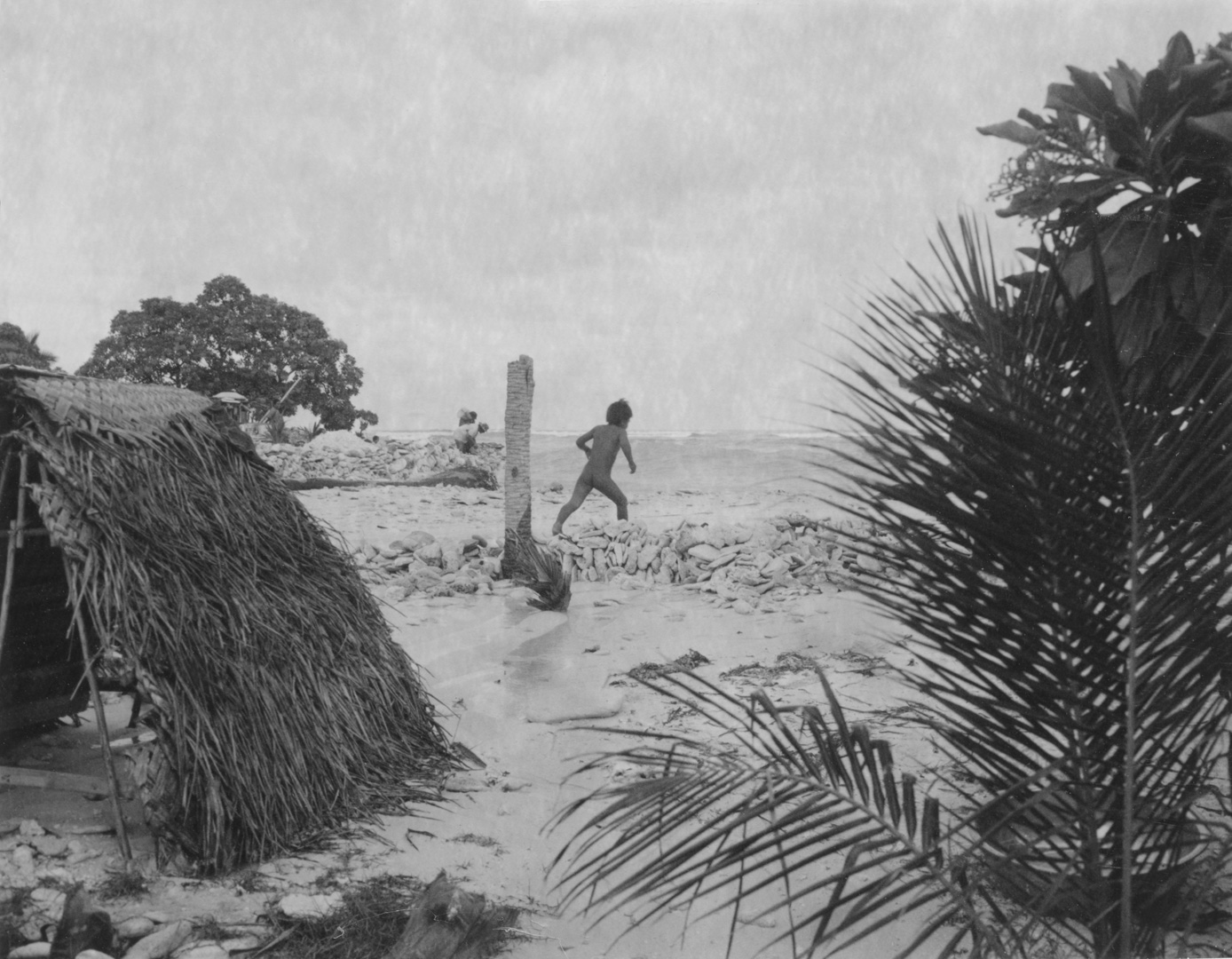

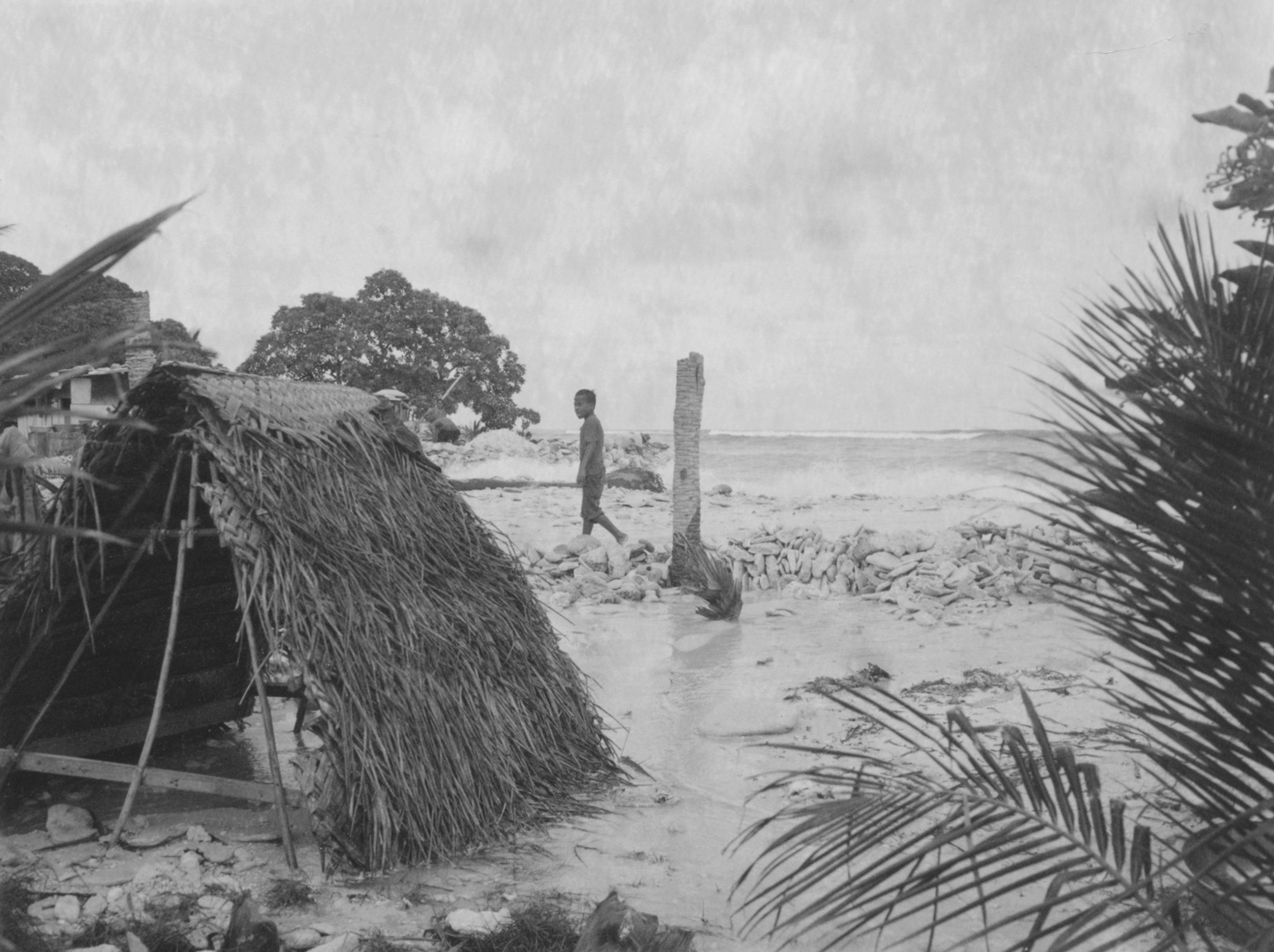

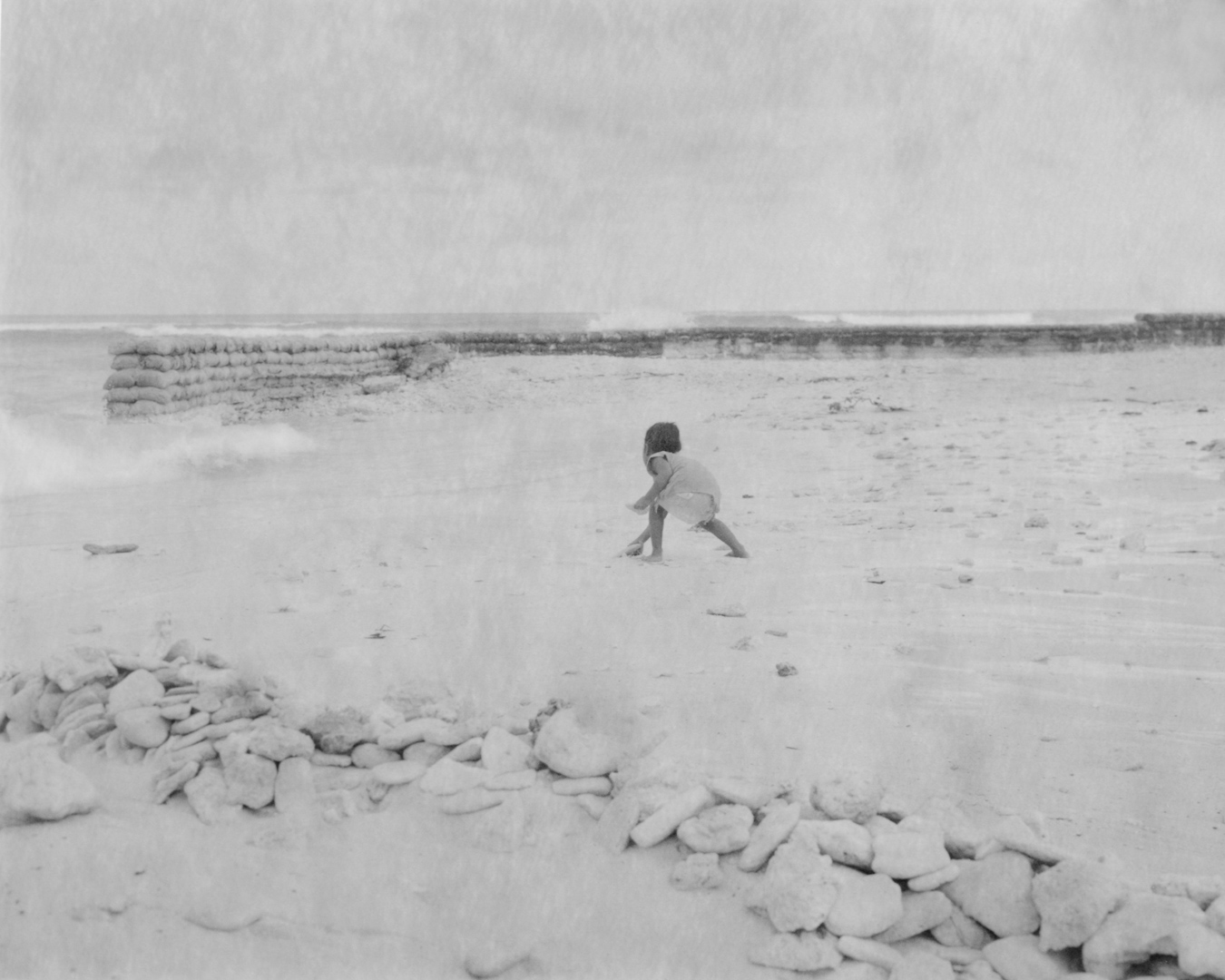

Meanwhile, the people who used to live surrounded by water are now living with their feet in it. Every day or so, the inhabitants move their houses a few metres away or tirelessly rebuild shell walls to withstand the onslaught of the waves. Surprisingly, without ignoring what is happening, the testimonies of the local population do not reveal any nostalgia for the past or fear of the future.

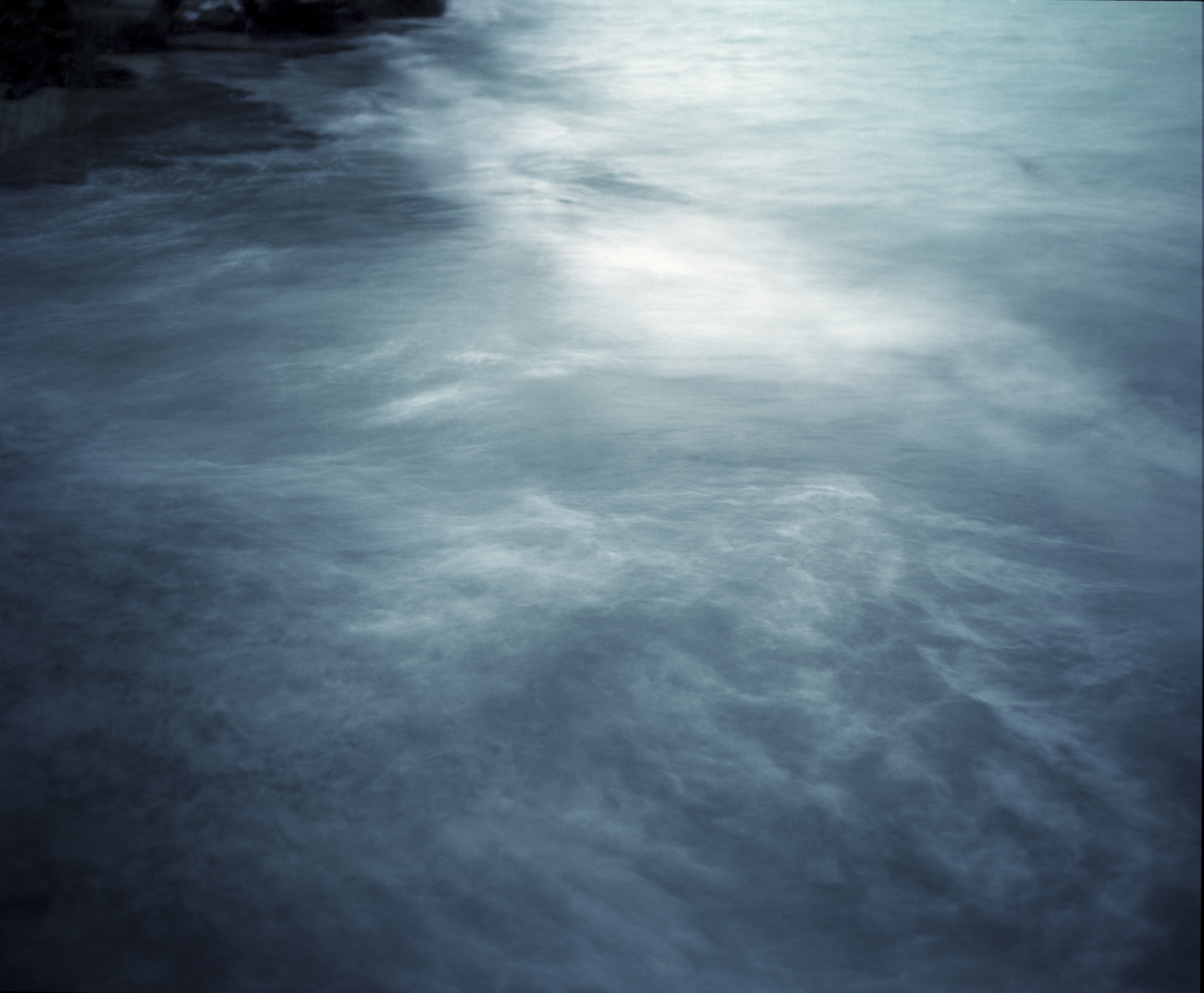

If the disappearance is certain, it is not always spectacular. Inexorably, the sea rises and floods the villages every day a little more. The increasingly unstable weather strengthens the storms and sweeps away century-old trees under the waves. And sometimes the rain disappears. Paradise is falling apart.

And yet the density of the air sometimes feels like a caress when the sparkling sea barely raises a soothing murmur. One could feel there how the world, on some days, offers us the deceptive impression of being a welcoming place, made to measure for man’s dreams and strangest desires.

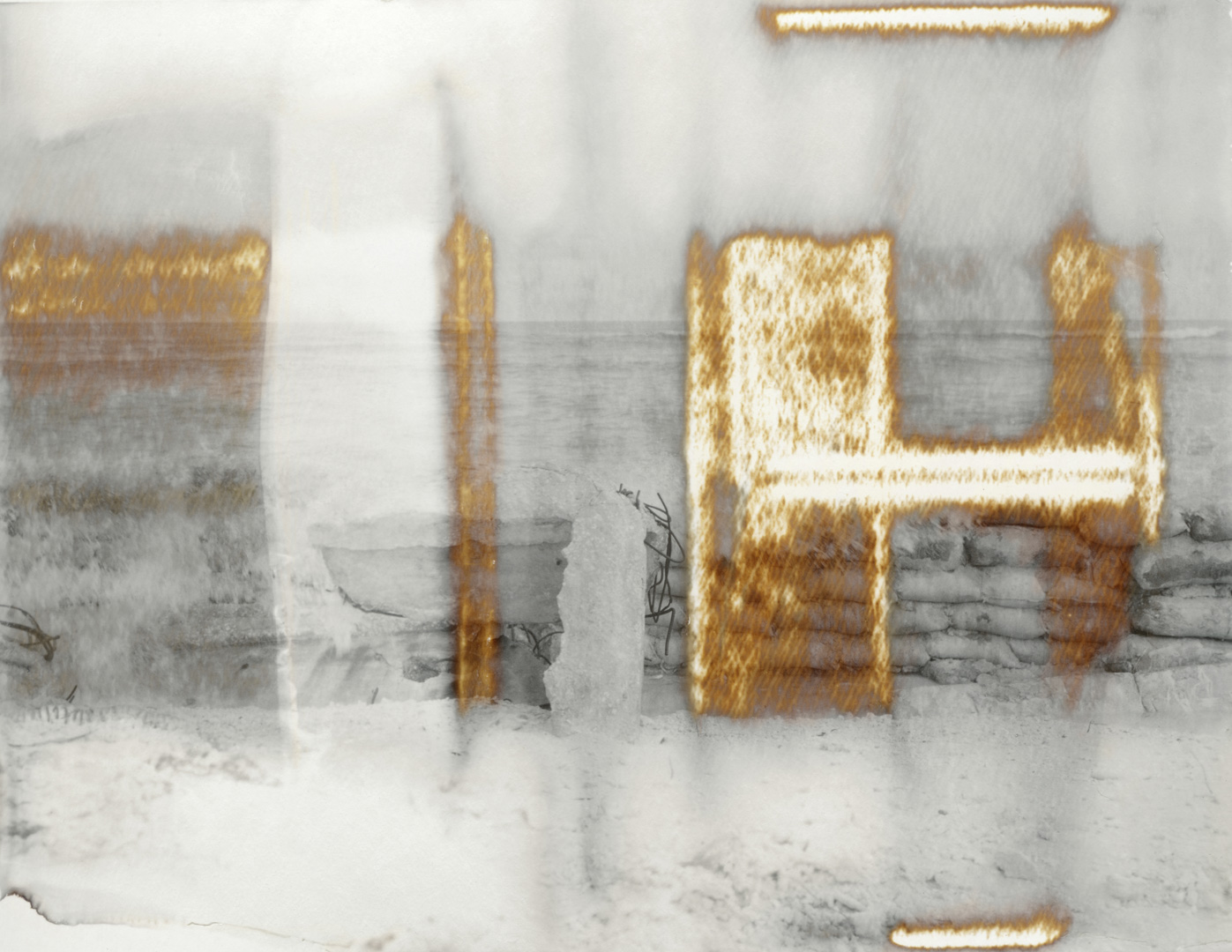

If the theme of disappearance fascinates us so much it is also because it permeates our photography. The use of obsolete films with altered chemistries, the entry of light into the bellows of our “home made” photographic chambers with old and imprecise optical lenses erase and veil our images. These absences that we claim provoke astonishment in us and allow us to glimpse a universe that our eye does not capture.

But here it is not only a question of disappearances linked to our writing. Caught up by our subject, it is he who disappears. These images will keep part of the secret, only allowing us to capture a world that is sinking by covering it with cautious attention right down to its cracks.

Aline Diépois & Thomas Gizolme