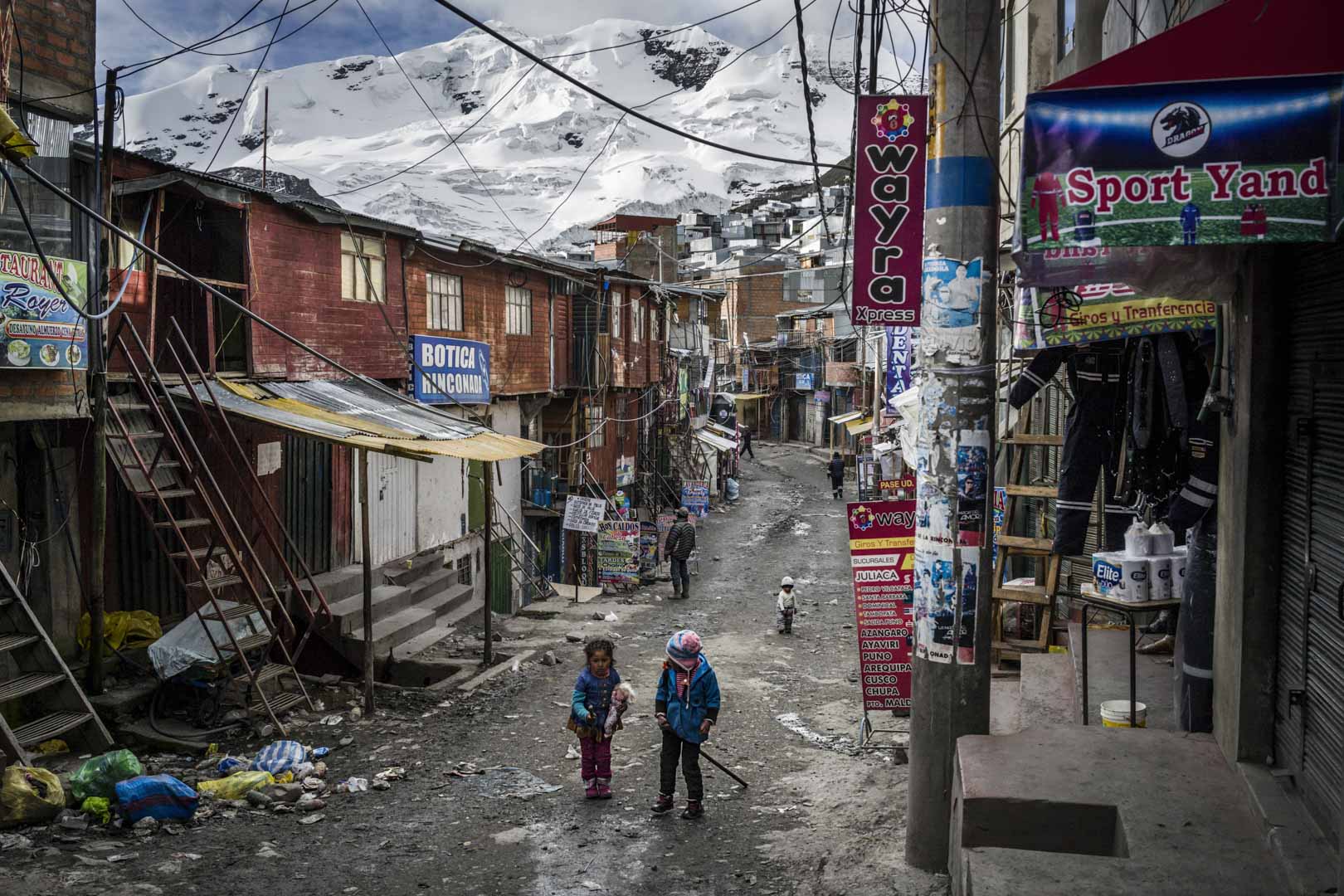

La Rinconada

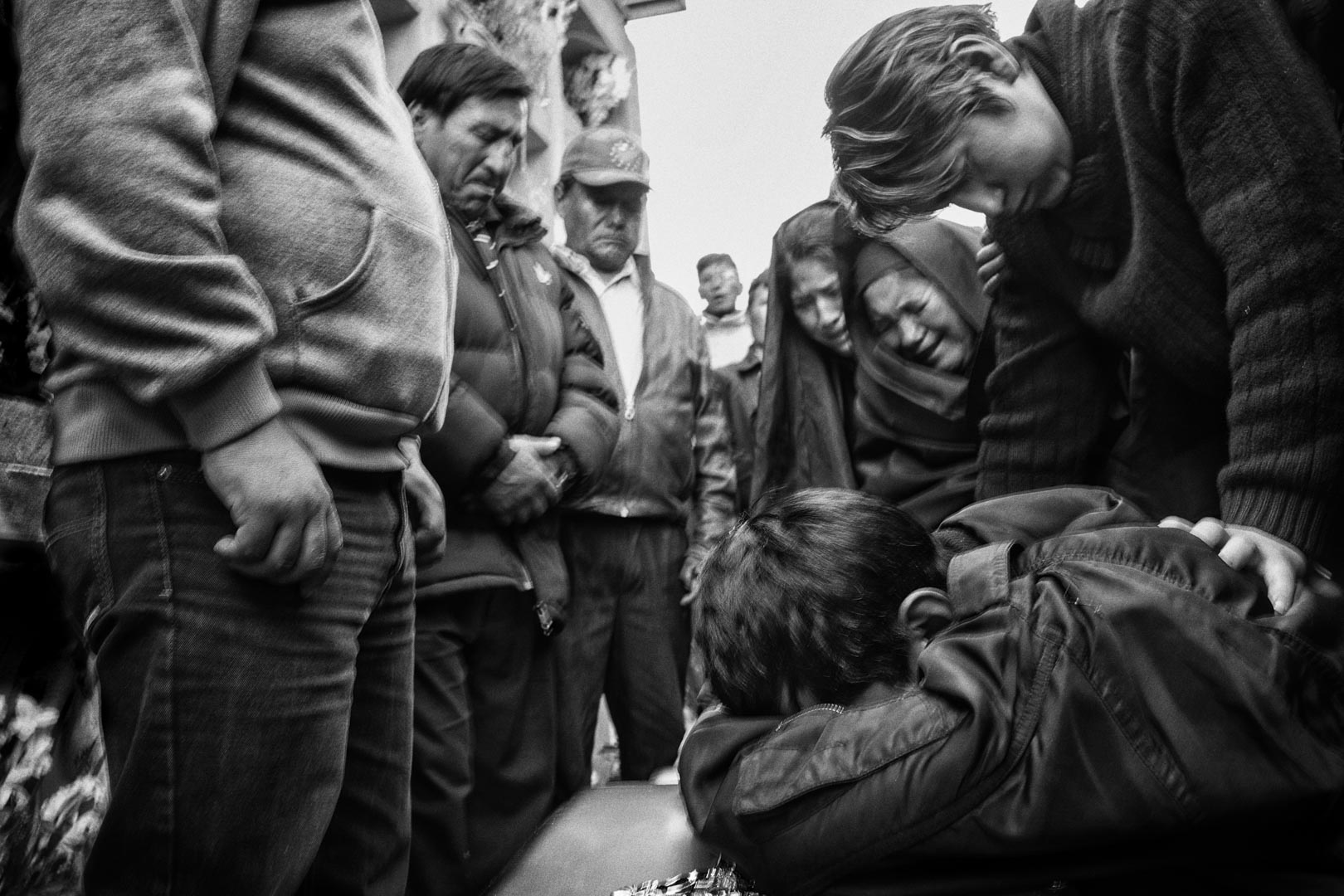

In the Peruvian Andes, La Rinconada is the highest settlement on the planet, a place whose bleak existence depends on the high price of its most coveted resource—gold. As the price of the precious element more than quintupled over the past two decades, what was once a small town in the shadow of snowcapped Mount Ananea has transformed into an uncontrolled sprawl of corrugated metal shacks packed around artisanal mine entrances and a refuse-choked lake. The biting cold and lack of oxygen at 16,732 feet above sea level leave even the locals gasping for breath, and it smells like what it is—a settlement with a transient population of some 30,000 to 50,000 people and no garbage collection or sewer system. Fatal accidents in the labyrinth of mines deep inside Mount Ananea are common, as are lethal brawls. Miners have been robbed or even murdered after selling their gold, their bodies left in mine shafts.

Some murder victims have been women and girls lured from larger cities in Peru and Bolivia by human traffickers who confiscated their identity papers and put them to work in La Rinconada’s dingy bars and brothels. Several small companies have claims in Mount Ananea, and one contracts out sections of its claim to around 450 members of cooperatives who are among its shareholders. The conditions in La Rinconada harm workers’ health and poison the Andean landscape, but that hasn’t stopped buyers and refiners in the United States, Switzerland, and other countries from purchasing La Rinconada’s gold, processing it, and turning it into bullion and brilliant jewelry. By that time, the gold bears no indication of its origin in poorly regulated Peruvian mines. International efforts to fetch better prices for gold from mines that meet higher standards have made no inroads in La Rinconada.

Cerro Rico

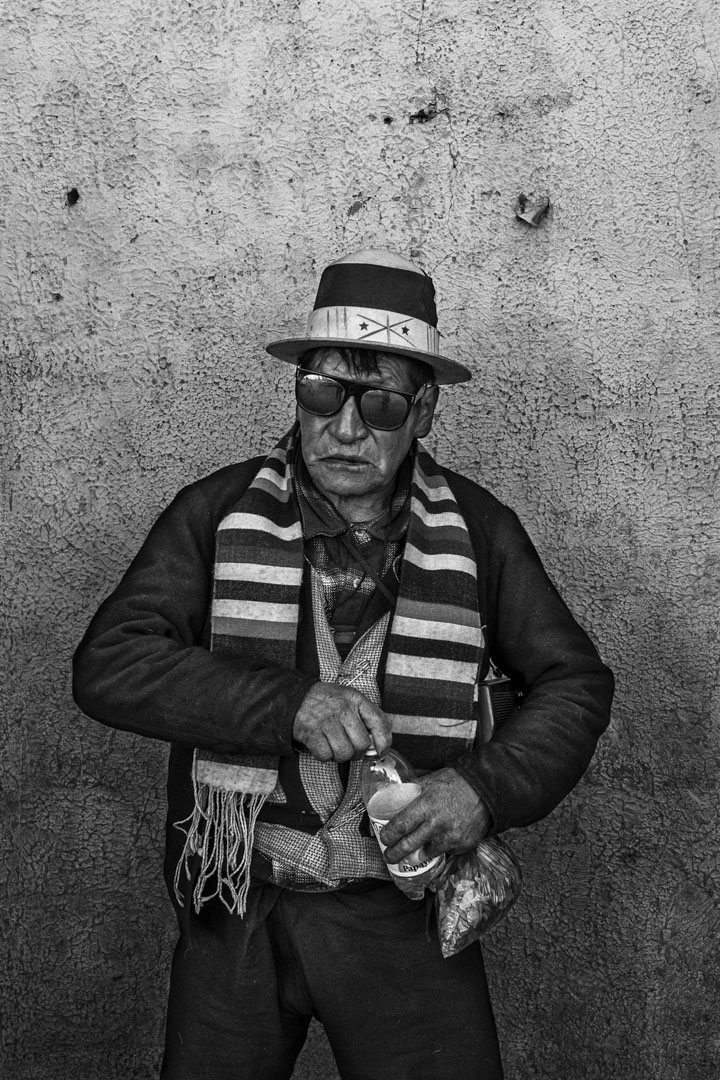

Potosí is a disconcerting example of how the economic system that enriches the industrialised world is facilitated by people who will never benefit from it themselves; people who – driven both by the world economy and their own desperate need to survive – are currently in the process of destroying the very place that provides them with this much-needed income.

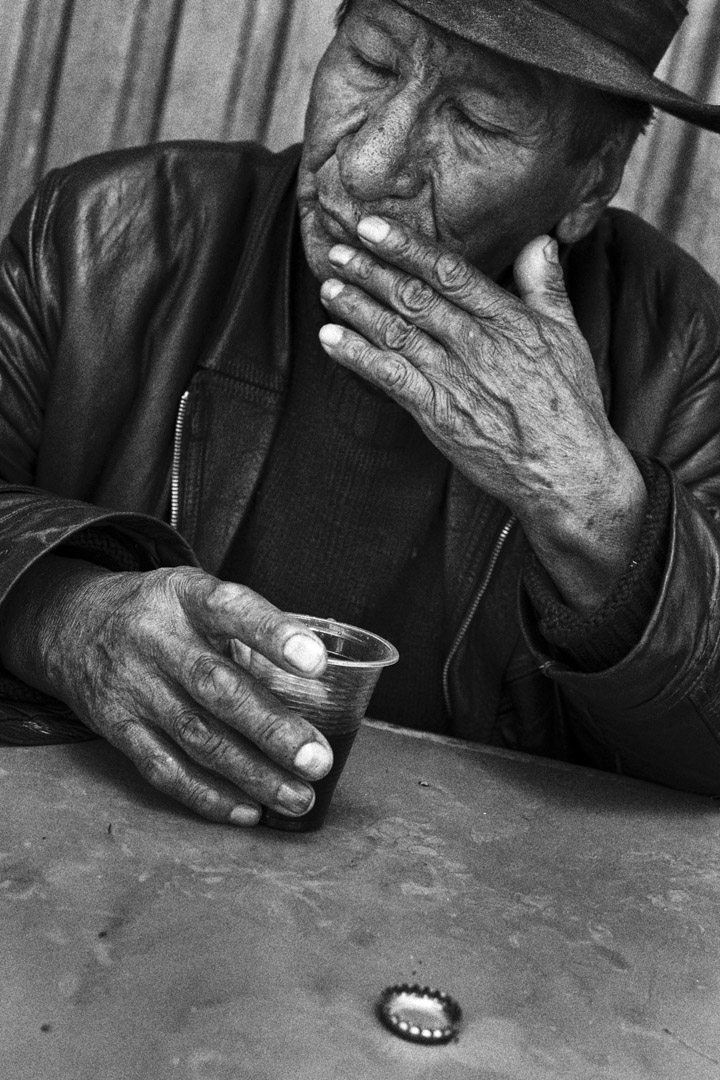

The Cerro Rico – the ‘rich mountain’ with an altitude of 4800 meters – is situated above the city of Potosí, historically founded by Spanish conquerors. Centuries of over-exploitation have left the mountain so riddled with tunnels that it would come as no surprise if it were to collapse in on itself at any day. So why are the mining plants, which in themselves are already run with shockingly low safety standards, not simply closed down? The answer is that mineral resources are among the few commodities Bolivia has in abundance – and that for the inhabitants of the barren mountain region, this is the only available source of work. From time to time protesting miners from Potosi clash with police in the capital, La Paz. They are calling on the government to make good on promises for public works and job creation in the southern Andean region.

In fact, Potosí is even expanding, as this is where people come when they give up on cultivating the barren highland soil. As a small cog in the global mineral-trade machine you can at least rely on a meagre income. Coca leaves and 90-percent alcohol make the daily grind more bearable. In the 16th century, the Cerro Ricco yielded the raw materials for the coins of the Spanish conquistadors. They subsequently flooded Europe with the currency to such an extent that it brought about the first inflation of world-historical proportions. Today it is predominantly tin and zinc that are mined from the mountain, largely for the global electronics industry. For anyone who has ever wondered what the supply chain that ends in our lifestyle accessories actually looks like, the area around the Cerro Ricco certainly paints a picture of where it begins.

Vale Grande Carajas

In Brazil, the Programa Grande Carajas, in the heart of the Amazonian forest, is the largest complex composed of several mines for the extraction of iron in the world. It is here that are located the main activities of the Vale company. This Brazilian company is the world’s largest producer of iron ore and the second group of extractions in the world.

Vale is also part of a joint venture that operates the Germano mine in Minas Gerais where in 2015 two dams broke, creating the worst environmental disaster in the history of Brazil. Vale operates the 890-km long railway that links the mines in the Carajas region in the Brazilian state of Para to the maritime terminal of Ponta da Madeira, Sao Luis, in the Brazilian state of Maranhaõ. It is on this line that circulates the longest train (3,5 km) of Latin America.

Composed of 330 wagons, its main cargo is iron ore but there is also a private passenger train. The fleet is composed of 220 locomotives and 20 000 wagons. 15 ore trains pass every day through 27 villages, some of which are victims of the pollution caused by the iron and steel industry and the coal industry necessary to transform the iron into cast iron, which is also transported to the coast.