Tchernobylsty, 2001

They used to live near Chernobyl, in the shadow of the nuclear power plant that symbolized the prowess which the great Soviet people had, their mastery of machinery. A lot of people worked there. They had even been built a city for them: Pripyat, with a population of 49,000, just three kilometers from Ukraine’s power plant and the ill‑fated Reactor No. 4.

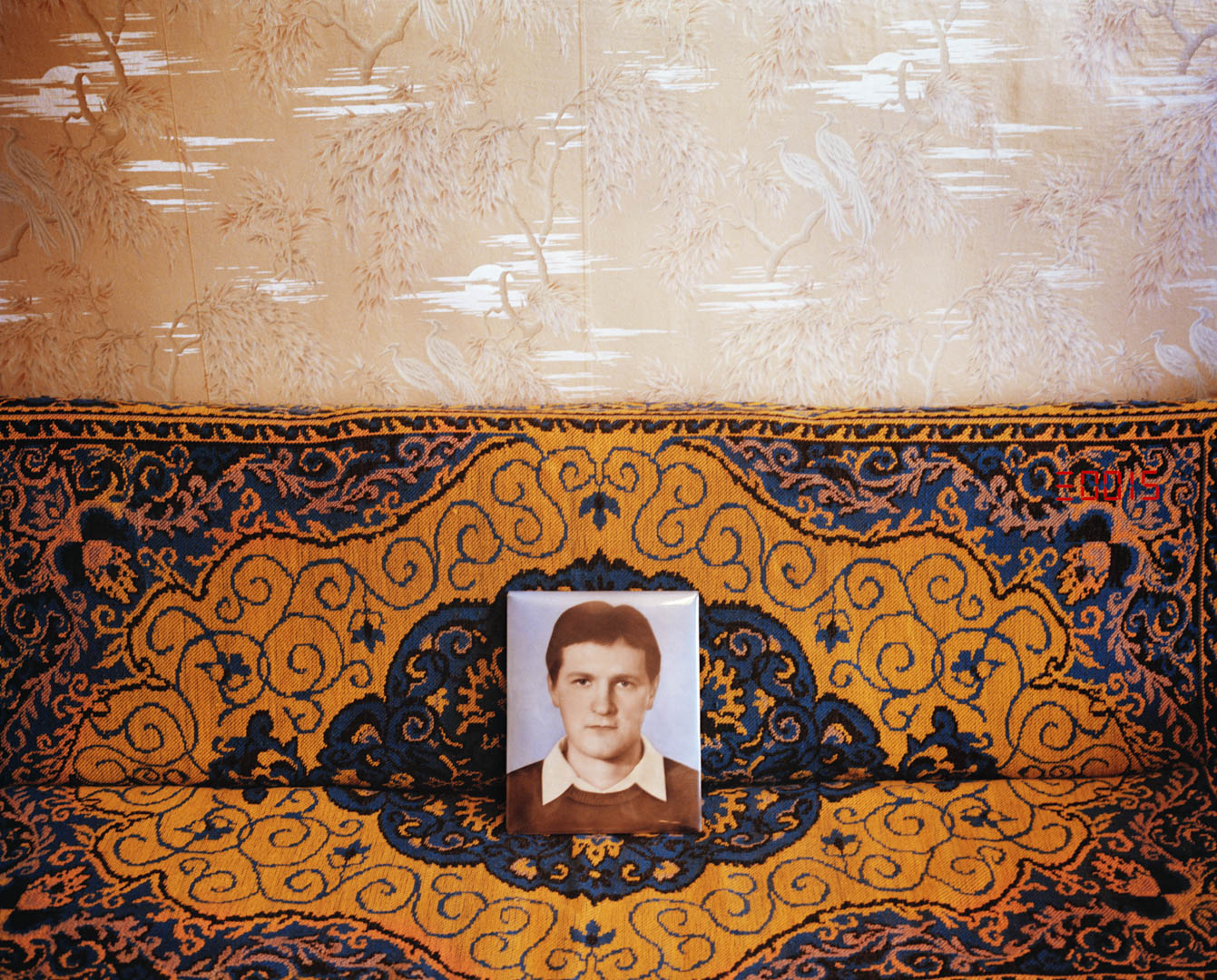

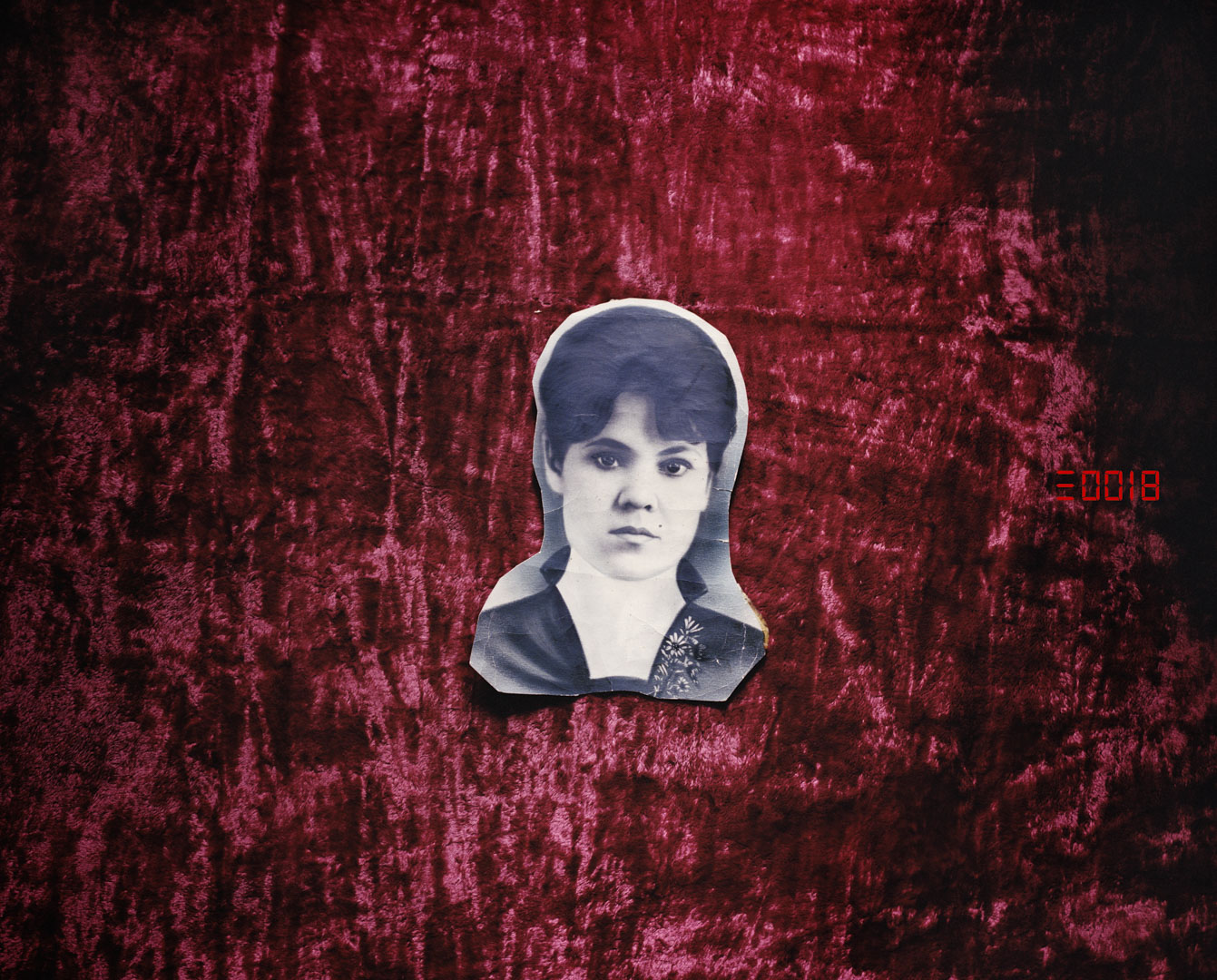

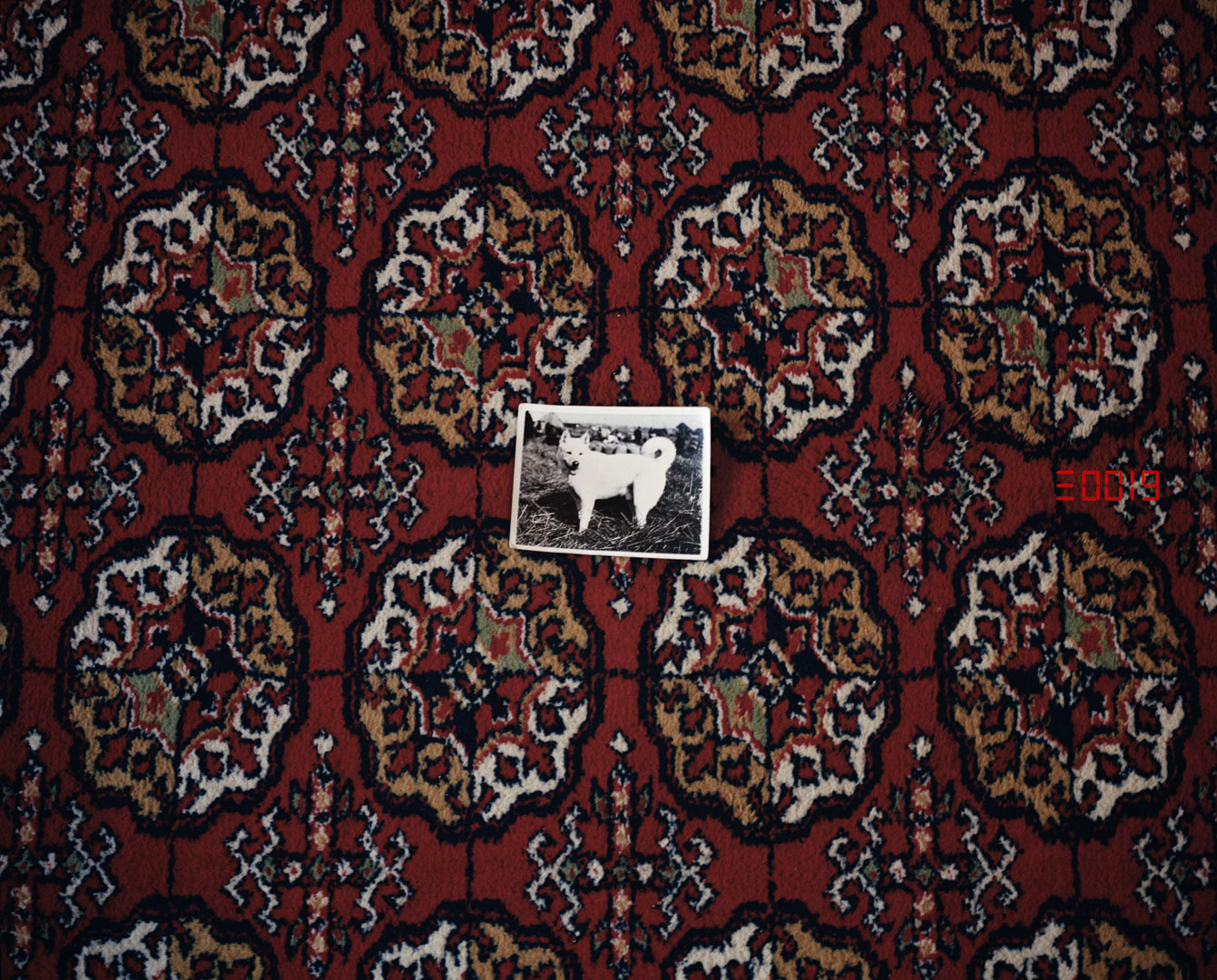

On April 27, 1986, the city of Pripyat was evacuated in the space of a few hours. Everything had to be abandoned; it was the same in all districts in the exclusion zone within a 30-kilometer [19 mile] radius of Chernobyl. Everything was radioactive. Nothing could be taken. Perhaps, secretly, just a photo or a piece of jewelry.

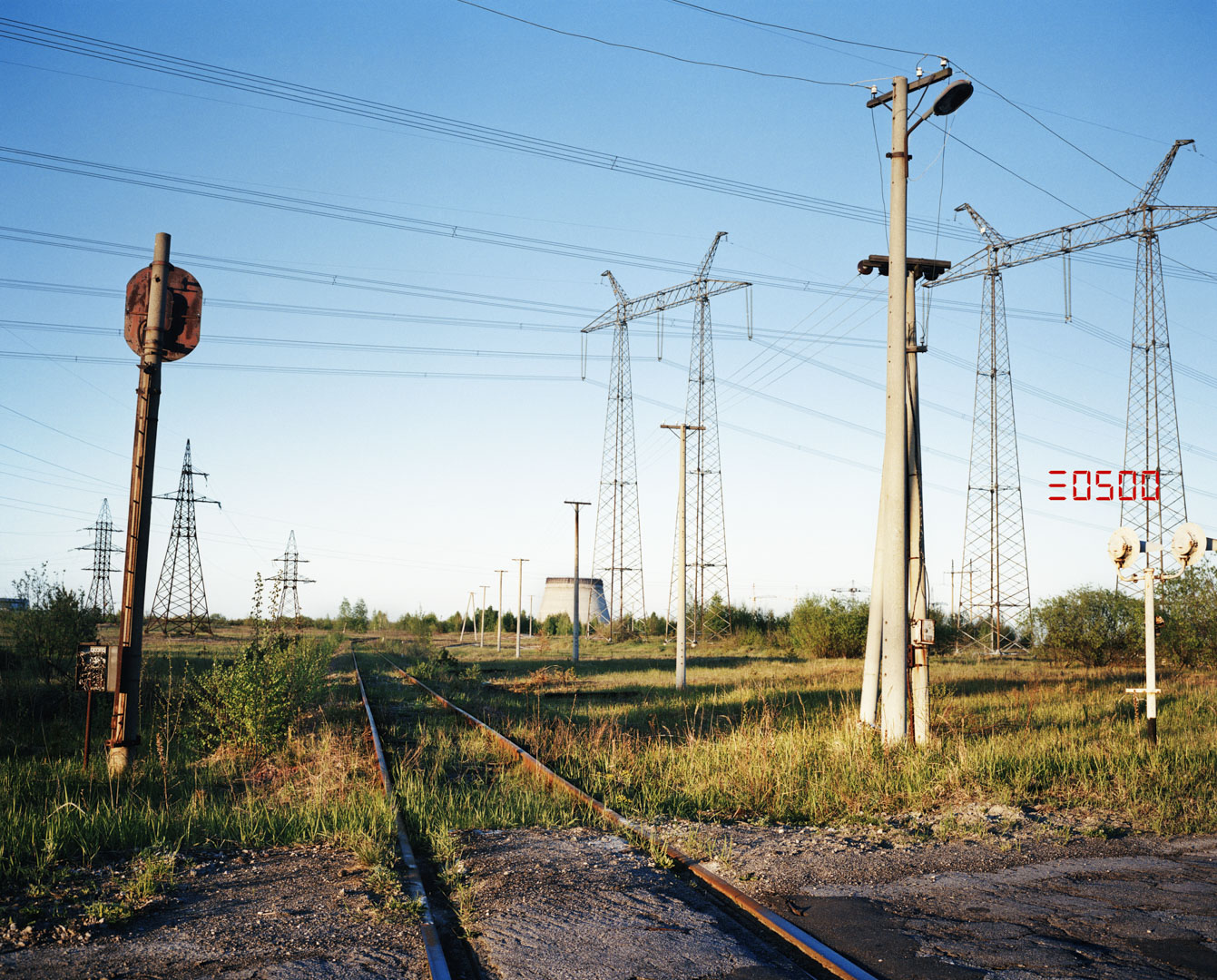

Fifteen years after the disaster, Chernobyl was finally closed down, and the “new” city which had seemed like heaven on earth for thousands of Soviet citizens at the time was more reminiscent of the apocalypse. The “glowing towers” were surrounded with barbed wire, seepage was running down the walls and rooves were collapsing. Trees had sprouted up between the paving stones breaking up the sidewalks. The same scenes of desolation were everywhere around the city. According to CRIIRAD (a French association for independent research and information on radiation), it will take more than 6000 years for some of the land to reach normal levels of radioactivity. Yet despite that, nature has prevailed over the “machine,” but it is a new form of nature, wild and formidably dangerous. No one can lie on the grass, or touch a flower or chew on a blade of grass. Nature is observed, as if it were a stage set in a theater. Many of the residents of Pripyat now live in Kiev, in outlying districts of what is now the independent, sovereign state of Ukraine. They were rehoused a few days after the disaster. These people, the “Chernobylsty,” have stayed together, forming a sort of ghetto, bound together by memories, disease, poverty and the death of loved ones.

The radioactivity recorded at the time the photo was taken is noted for each picture in the Chernobylsty series by Guillaume Herbaut.

A normal level is between 10 and 20 microrems.

“In times past there was fire or tempest, but a disaster inventory now needs to include nuclear blasts, catastrophic events that rival the phenomena of yesteryear such as the wrath of the gods. First there was the icon of the evil mushroom cloud; then there was Chernobyl.

The real impact of the drama defies the scope of visual presentation. The threat is invisible, and on the human scale of time, it is infinite. For years Guillaume Herbaut grappled with the challenge of conveying Chernobyl in pictures. There was little in the way of symbols or allegories, and to replace the invisible with things visible, a frontal approach to the story was the prime requirement. Face-to-face confrontation was the visual protocol for revealing the invisible enemy.

The frontal approach presents us with the survivors, and also the dead, present through photographs displayed, through fetishes or samples. Then there are the doors, epitomizing a frontal relationship which, at last, offers the key to the meaning of this perspective on Chernobyl. By facing things head on, there where evil radiates, the story of the victims of fate is produced. The victim of fate is the only being capable of being the face of the inescapable force. The victim of fate is gifted with sight yet deprived of horizons. Guillaume Herbaut thus offers the possibility of using images – images of victims of fate – to address invisible forces.”

– Michel Poivert – Photography Historian