Sète, 2013

This is Sète in winter. Sète in black and white, as Cédric Gerbehaye saw it.

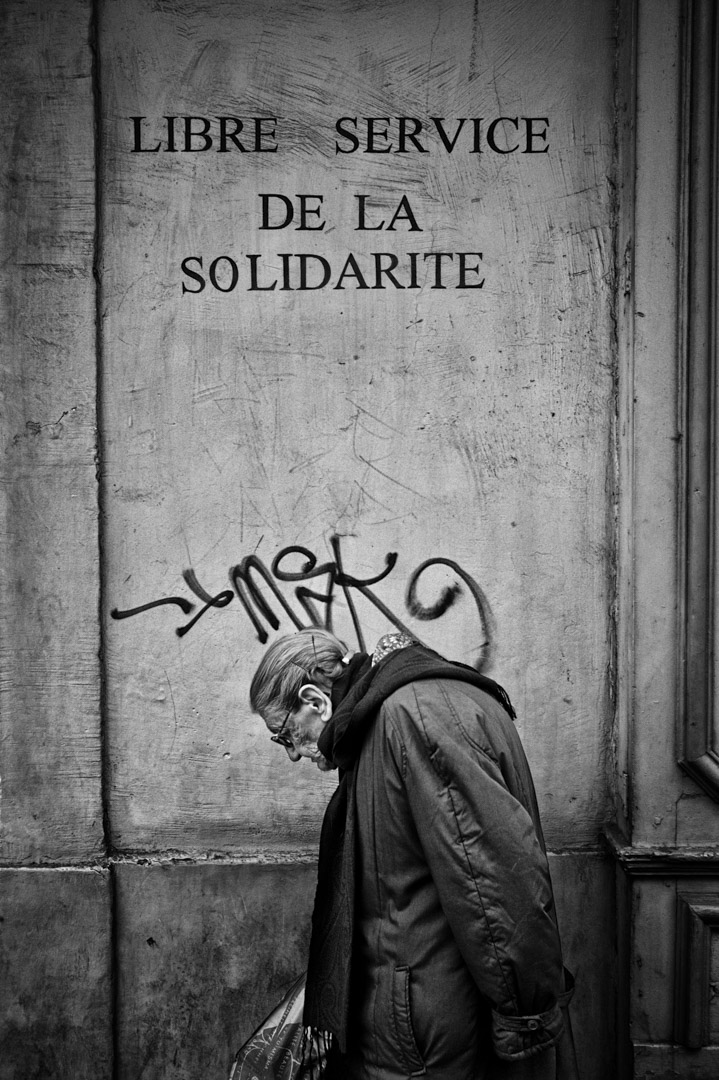

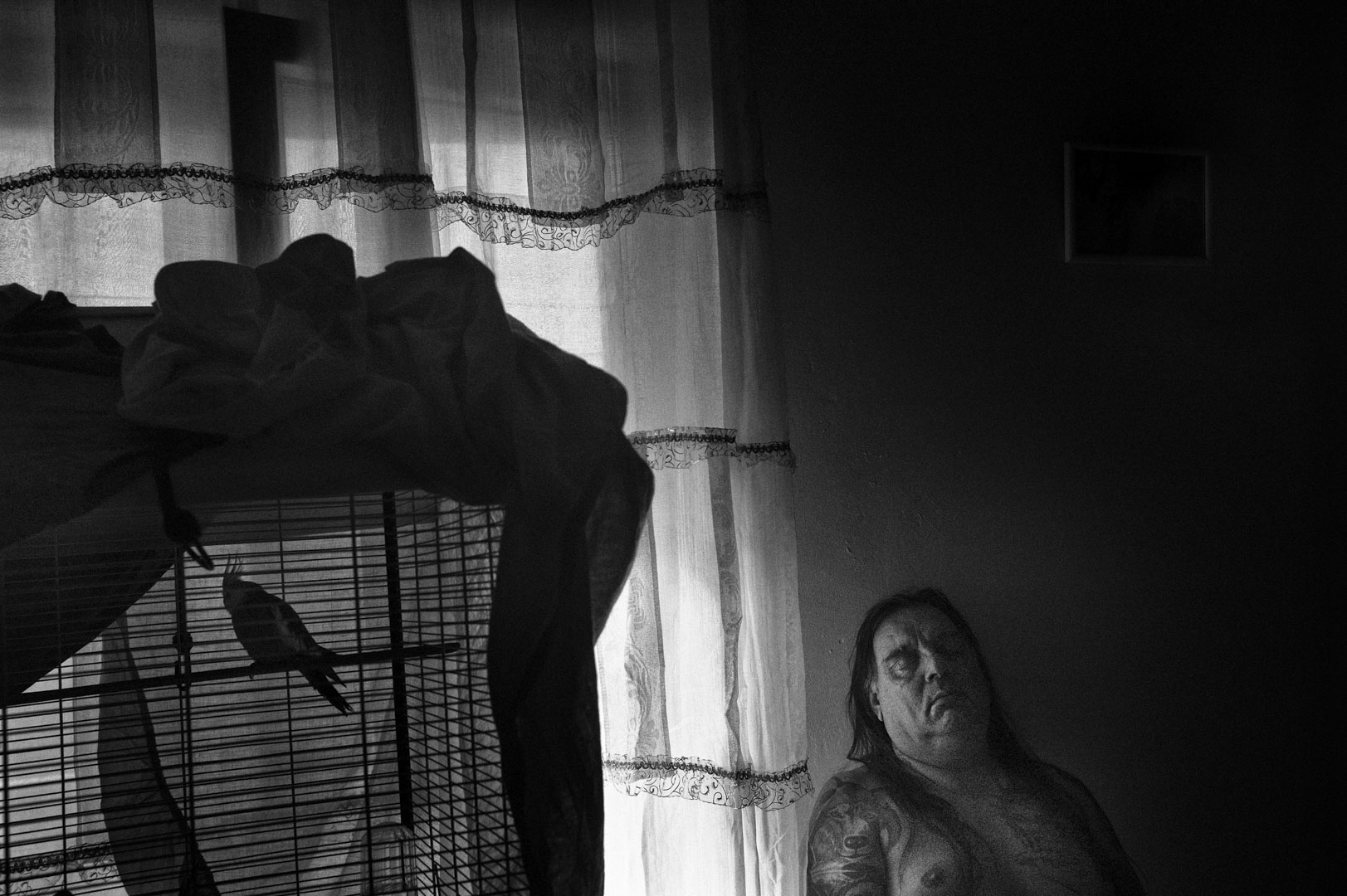

Sète is closely framed, and precisely. As though with a scalpel; or so one might say, were it not for the risk of giving the impression that there is something cold here, and dry. The formidable acuity of the eye is in effect qualified by the vibrations of the winter light, which reveals without exulting, and modulates without caressing. No small talk, verbiage, vapidity; no temptation to narrate, or to explicate. No road map.

Sète in winter, in black and white, looked at in the most accurate manner possible, comes through as the opposite of the clichés: a quest for sunshine, postcards, colour, excess, Mediterranean.

The sea is as grey as the sky; and the birds, in becoming images, have taken on a blackish tint. Time is strangely heavy, and seems to have difficulty in passing. It stagnates in durations impossible to determine, in territories that allow the sea to appear in them, but not to spread across them. Without really hurting, Sète in winter is problematic, like a breakdown.

Perhaps Sète is hibernating. And those who live there seem to be on their own. Isolated. Even the dog and the cat are alone. Is this because the space, in the port and along the shore, and even on the canal, along which a solitary boat is gliding, is structured around the only lines that brighten or darken what comes down from the zenith, filtered by sky?

Sète – more singular and enigmatic than ever, because we never, finally, want to see it or look at it in winter. But Sète, amazingly strong on its axes, its directions that capture the eye. Right up to the point where a wall or a shuddering facade, like a massive doubt, cannot be known to any further extent.

(Extract of the text by Christian Caujolle / Translation by John Doherty)