Romanian Rip (Timisoara), 2008

Timisoara is the town from where started the Romanian revolution in December 1989. Twenty years later, it enters, with its country, in the European community. Two groups live together in this town: those from before and those from after the 1989 revolution. Those who were over twenty-five in 1989 had difficulties to adapt to capitalism. The younger live fully this new system. To show the two faces of this society, I have photographed Timisoara’s life machine: industry, commerce, authority, leisure, family. The caption on each photograph indicates the age of the people, some of whom were witnesses of the revolution, witnesses of the truth.

Because the true story is still uncertain. In December 1989, following an uprising from the people of Timisoara, the media announce 12,000 people dead, killed by the army and the Securitate, the secret police. There is talk of a genocide. To prove the executions and the tortures of Ceausescu’s regime to the western media, eager to get carried-away, the organizers of the uprising put together a staging. They dig up from the cemetery and lay down on the floor nineteen corpses of people already dead for several weeks. Journalists from the international press photograph this mass grave with a man crying over the corpses of this wife and his young daughter. What they don’t know is that the man is paid to play this part, the woman died from a cirrhosis and the baby, who is not his child, was a victim of infant sudden death. In fact, eighty-nine victims were officially counted in Timisoara and six hundred and eighty-nine over the country.

Since this spectacular manipulation, Timisoara symbolizes the doubt towards the images and the media. The staging replaced the information, the fiction has crept into the reportages. Even though a photographic document is suspect by nature, we often want to believe in it. The photographer is manipulated by his subject just as much as the subject manipulates him. By inserting myself in each image, I wanted to raise the question of truth in the photographic image. The fluorescent orange of the shutter release, clearly visible, asserts my intrusion inside the image. I thus sign the making of the document and its origin.

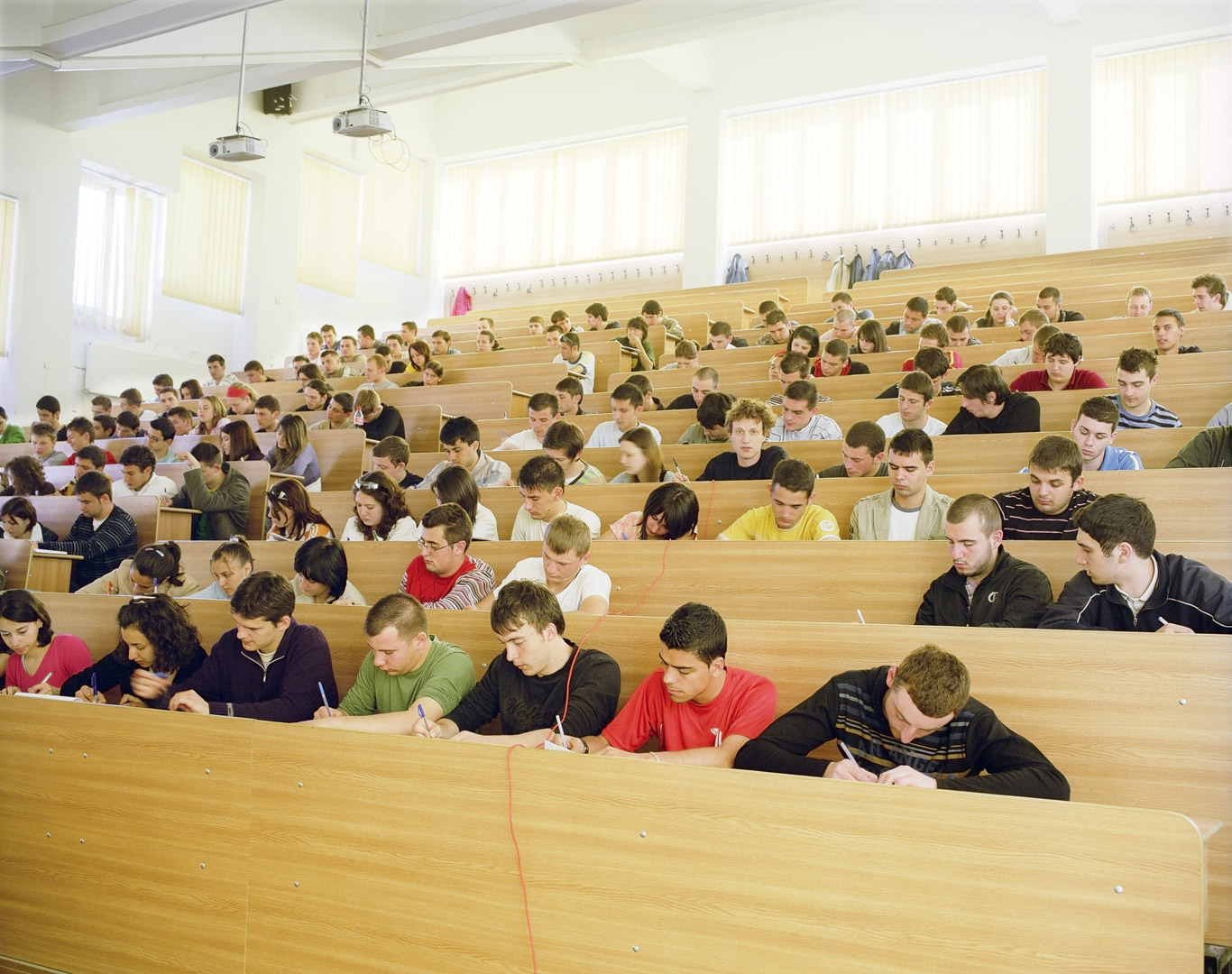

At the same time, I try to merge into the image. By dressing up and by behaving like the people photographed, I strive to erase our representations of nationalities and social backgrounds linked to the dress code. Strangely, no-one considered this approach as being odd and all said they felt more at ease in front of the camera when I was with them. Absent from the caption in which the other names betray the Romanian, Italian, Serbian, Hungarian, German, Austrian or Turkish origins of the people I photographed, I question my position and the imaginary barriers raised by men between them.