Patagonia, The Damned and the Beautiful, 2012

Aysén, Chile, a region of some 92.000 souls, sits in one of the most remote and undisturbed areas of the world. Its ecosystem is among the most remarkable still in existence. The area is home to some of the rarest plants and rainforests, many endangered species of animals, pristine rivers with high aquatic biodiversity, and the largest ice fields outside of Greenland and Antarctica.

From 2007 to 2014, HydroAysén tried with the help of the Chilean government to construct five dams and hydroelectric plants on the Baker and Pascua Rivers, in order to support Chile economic growth, its mining industry in the north and the increase in energy consumption.

Constant pressure from citizens, and the recognition of irreparable damage to the area caused the government to finally reject the project in 2014.

The dams would have created artificial lakes, irreversibly altering the ecosystem, flooding good ranching land, ancestral homes, damaging a traditional way of life and unexplored land, unknown even from most Chileans.

Patagonia would not have been the only area irretrievably disfigured. The energy would have traveled to Santiago over a 1,912-km transmission line, demanding a forest clear cut some 1,600 kilometers long and 122 meters wide, roughly the distance from Boston to Savannah.

I have made one extended trip to the region, photographing Patagonia’s endangered landscapes, its way of life and the people directly affected by this project. I have been photographing in Chile for 10 years now, mostly in the north of Patagonia, in Chiloé. When I was a child growing up in Belgium, I met a little Chilean girl, Pilar, who had escaped the regime of dictator Augusto Pinochet. Pilar was too small to talk about things like “exile,” “dictatorship, or “desaparecidos.” but her only presence changed the way I perceived the world. I imagined new stories, lands, and other people’s lives, images that stayed with me for a long time. Years later, these stories drove me to go and photograph in places like Palestine, Colombia, and Chile, of course.

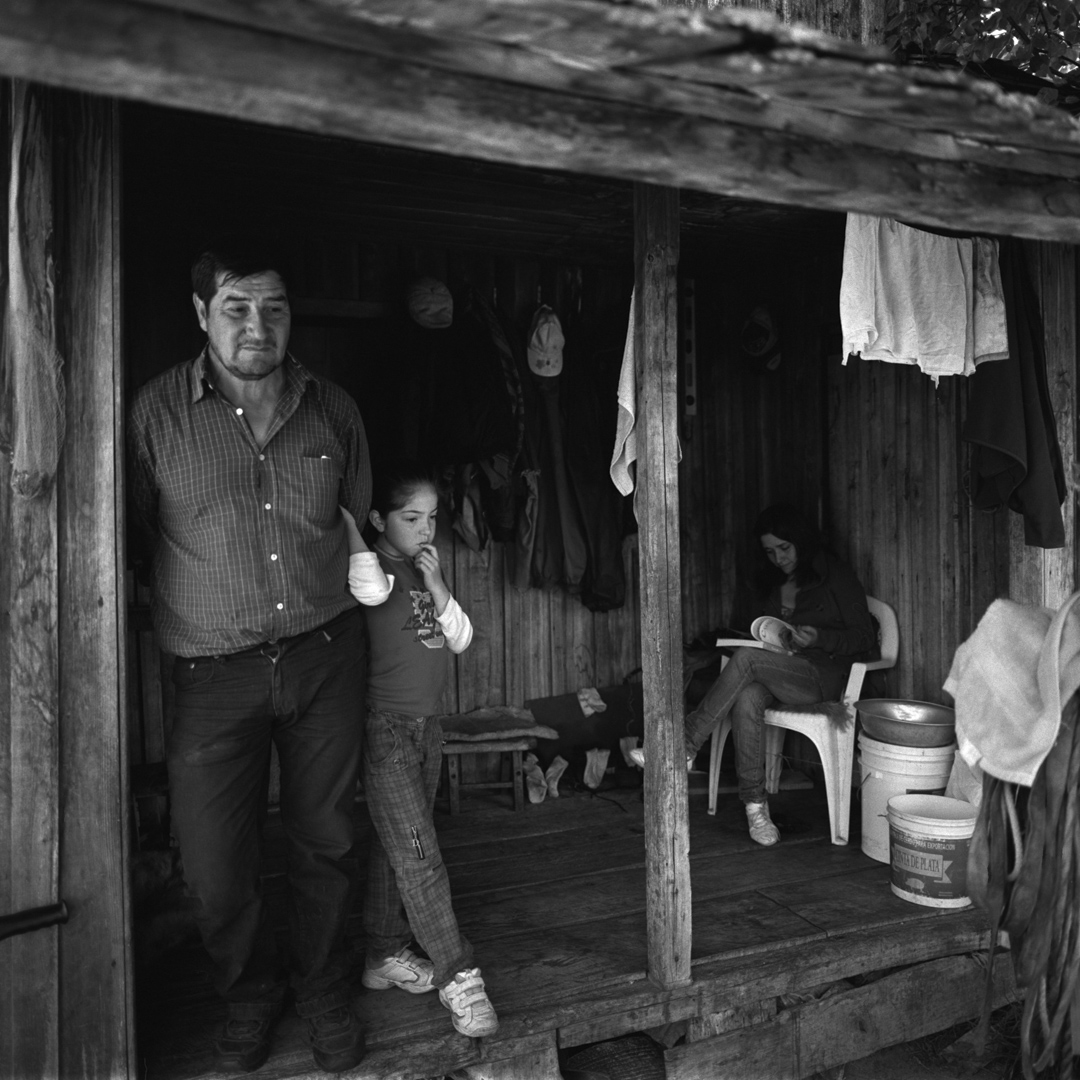

During my trip, I visited communities along the electric line. Life is difficult in this region. The cost of living is higher than in the rest of Chile, due to its isolation. The main road that serves the area, “The Carretera Austral,” is mostly a gravel road. Traveling depends on weather and volcano conditions, changing boat schedules, the difficulty to communicate. Many people don’t have electricity. They can only communicate by radio. Men live alone, their wife and children live in small towns, to allow the children to go to school. They are reunited during the school holidays. This is when I visited them, when families are together in their farm.

Patagonia is a mythical place that appeals to everyone’s imagination. Traveling in the region is difficult and it is therefore even more important to capture and sensitize people to its nature and to the threat it is facing.

One night I was standing on a tiny island in the south of Chile and my friend’s grandfather told me :”When you look at all those stars, how could someone claim there is no God?” For as long as we can recount, traditional and indigenous people have been celebrating our relationship with nature in their songs and stories. These days our society has gradually become disconnected from the natural world, and therefore lost any sense of responsibility towards it. In the process of the so-called world’s development, places sitting at the edges of the world are being destroyed and something is lost forever. Beyond the disastrous environmental consequences, something else is being sacrificed: our connection to our roots, our history and diversity. It has been a long-standing tradition and motivation for photographers to record what is threatened by demolition or the passage of time. Aysén is a rare and precious place, with a unique culture, a mix of tehuelche roots and pioneer spirit. Lilli says: “There is no land like ours.”