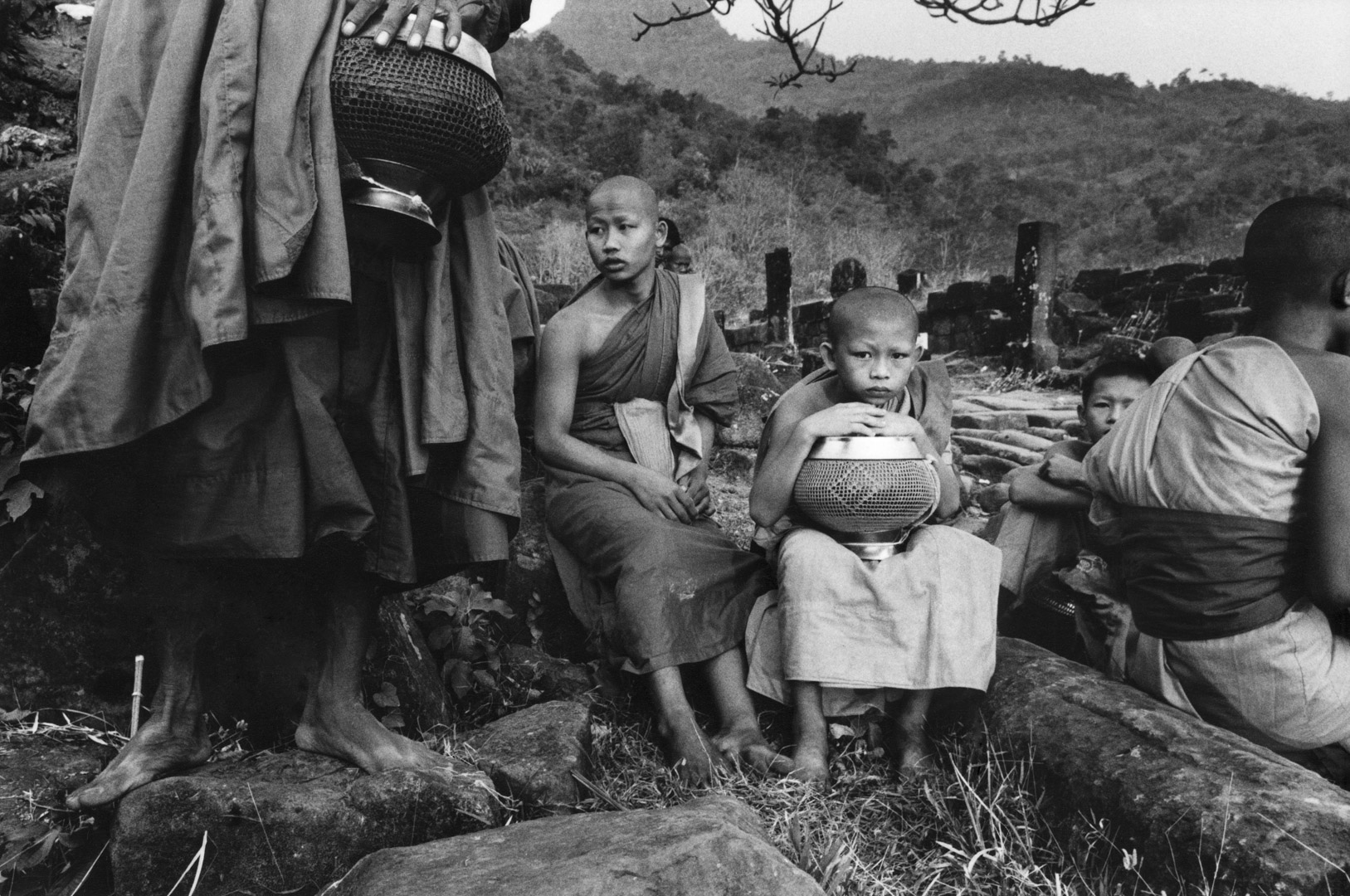

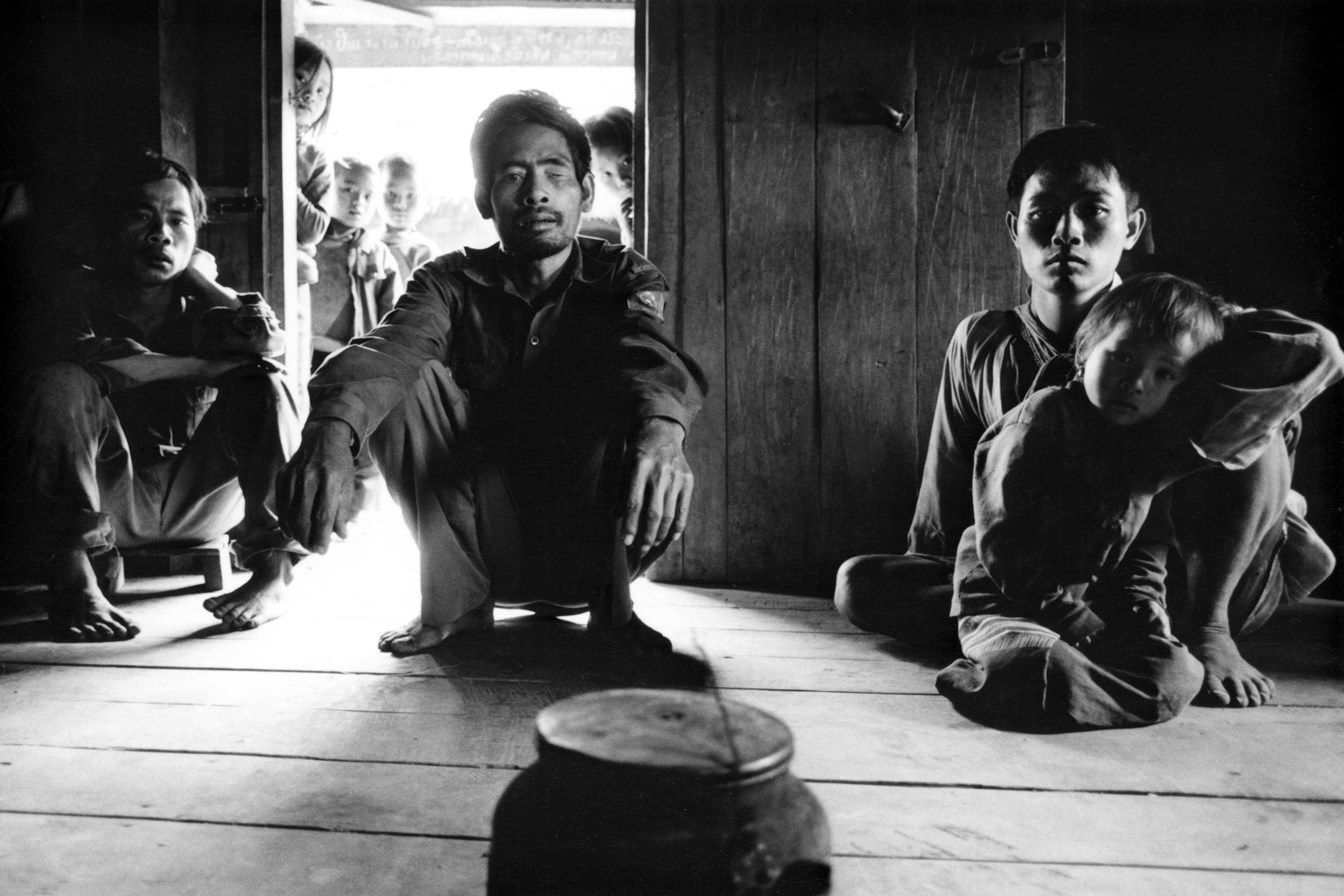

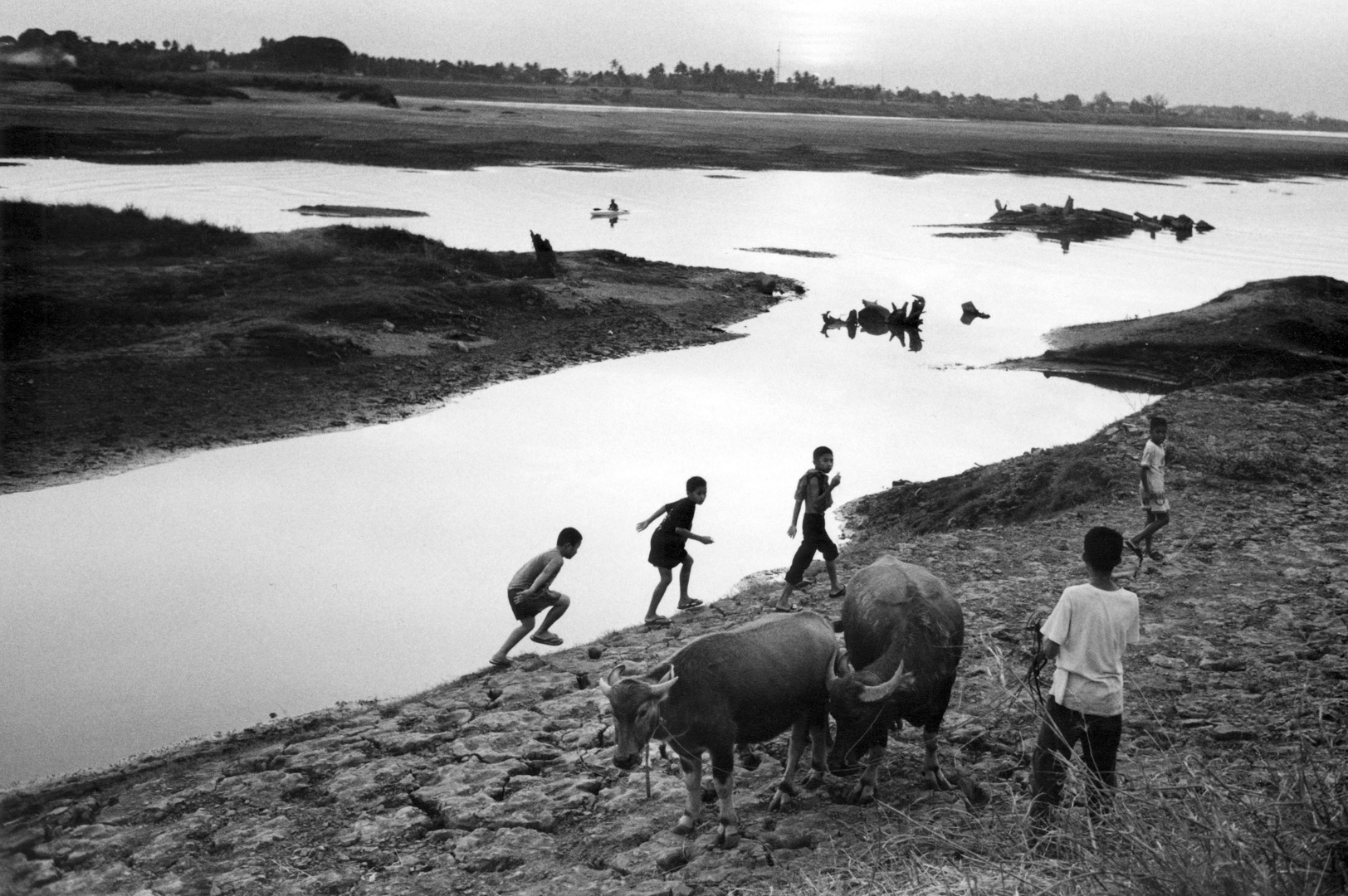

Laos, 2001

This photographic work by Yvon Lambert on Laos was carried out over a two-month period (December 2000 to February 2001) with the support of the Luxembourg Ministry for Cooperation and Humanitarian Action.

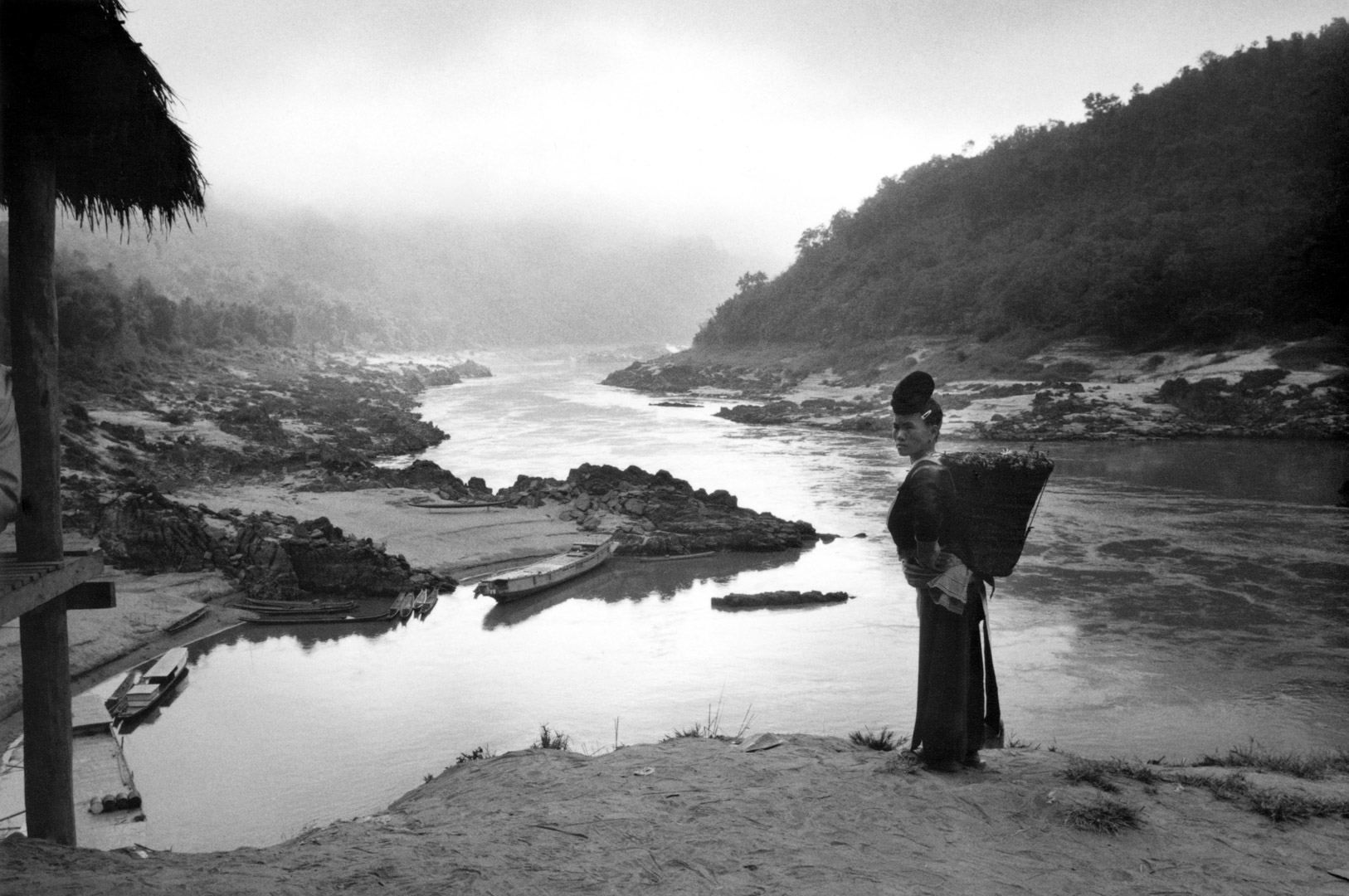

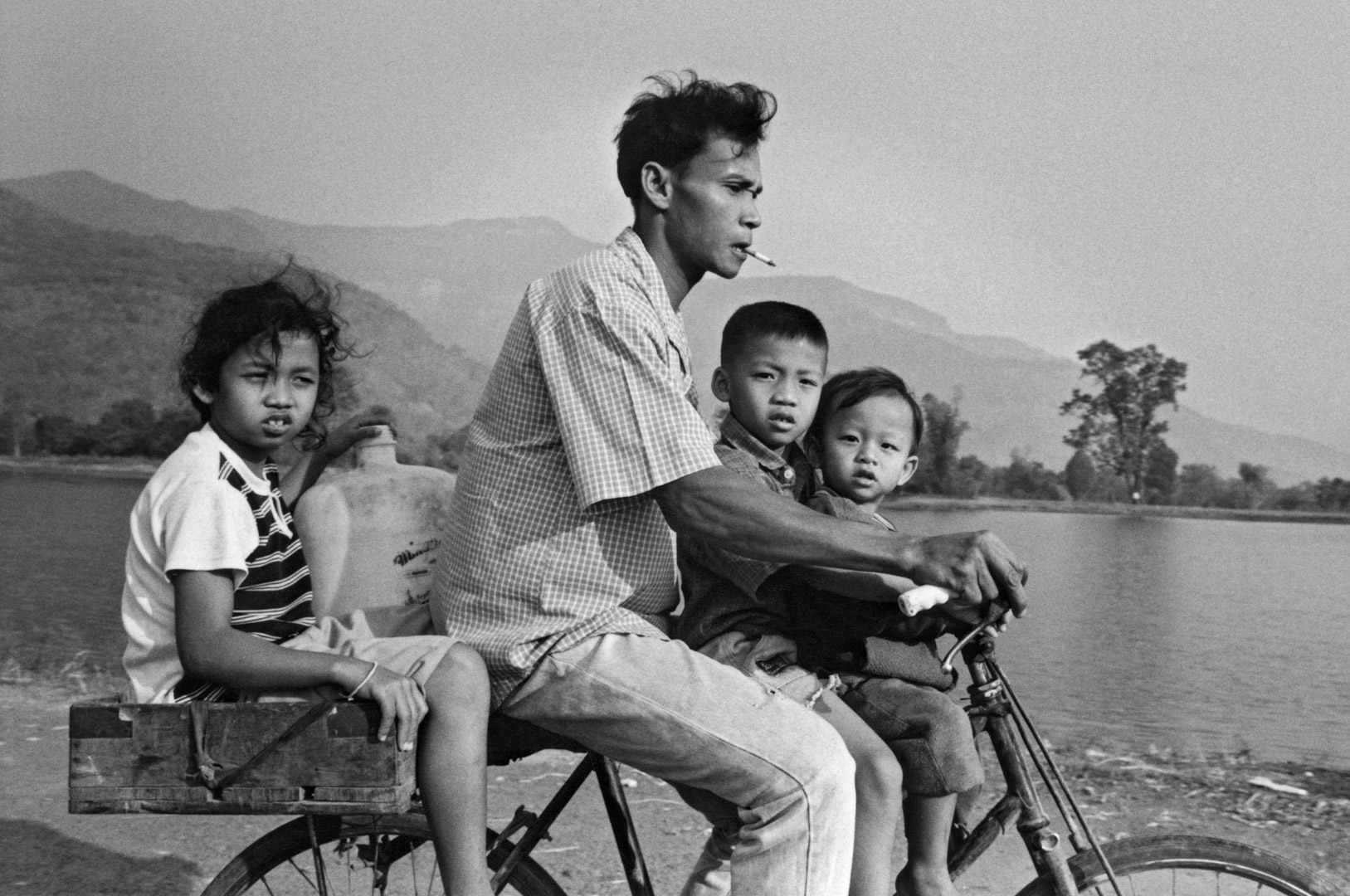

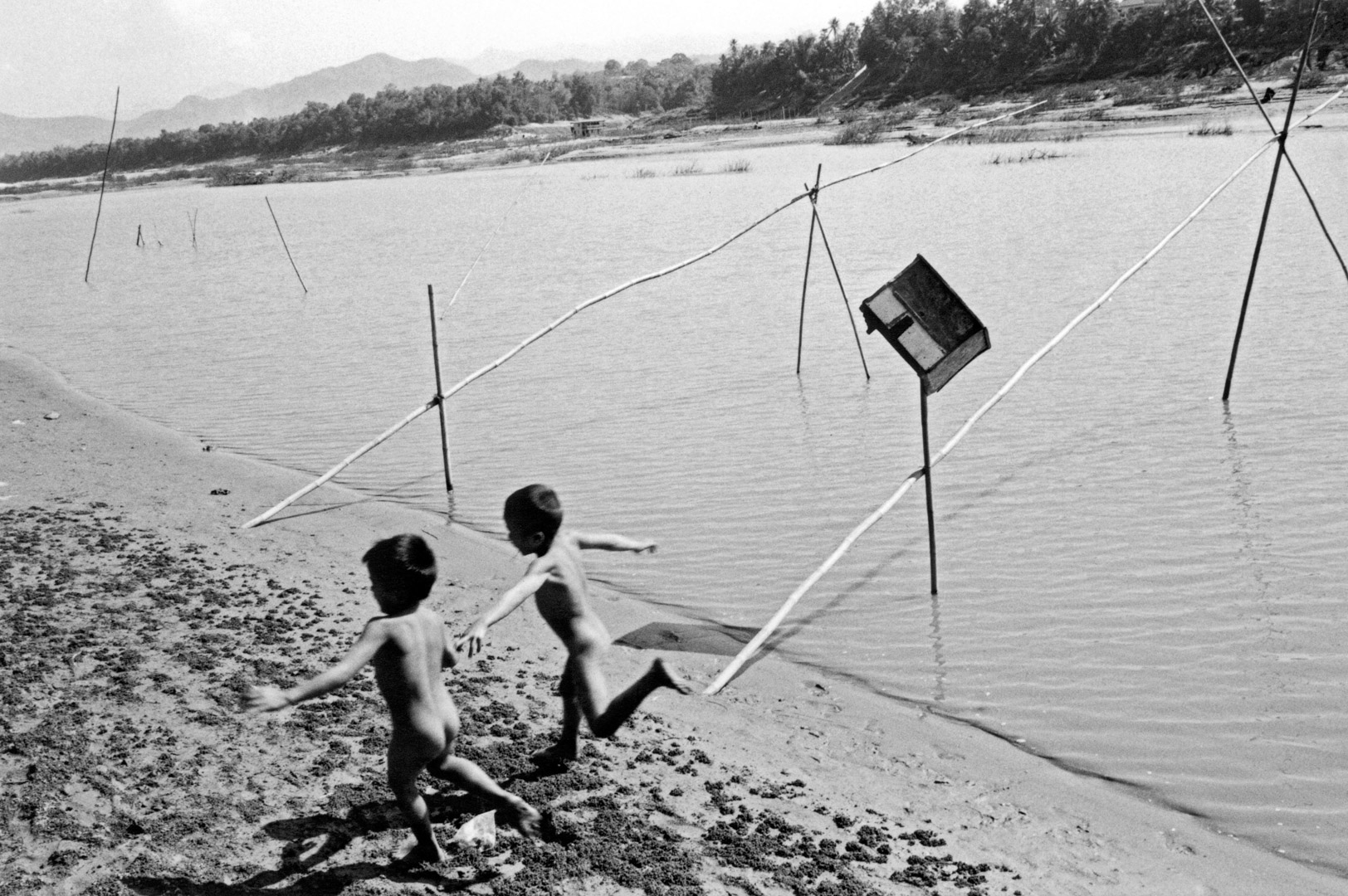

Along the Mekong River, a vital artery of Laos, the photographer reports on the daily life of the Laotians.

A book is still being planned under the title Au rythme du Mékong, le Laos, Alain D’Hooghe wrote the preface:

A clammy slowness

What do Yvon Lambert’s images show us? How do they fit into the essential album of knowledge?

These are not press photographs, at least not in the sense we understand it today since we now need hot news or people to attract the favor of newspapers and magazines. Here, there are no major events, no burning news, no war or disaster. No more stars or princesses, either.

Nor is it this photography that is increasingly present in the field of contemporary art. There is no so-called “objective distance” (or “distant objectivity”, that is to say), no diversion from the dominant iconography. No research on the material or ode to banality.

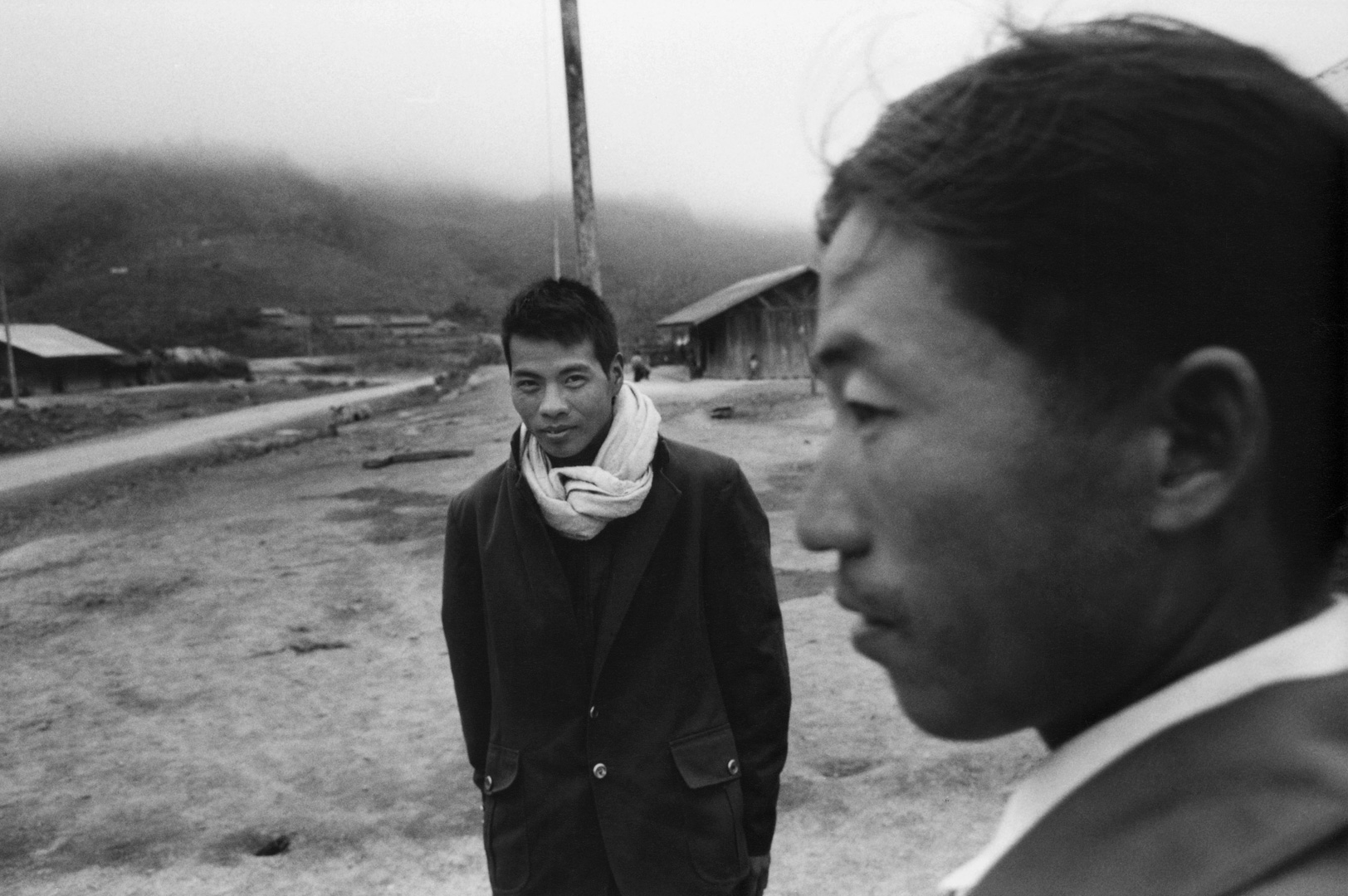

Yvon Lambert practices what is known as documentary photography or more precisely photographic essay. For him – like many of his peers who work in the same field – photography is much more a language, a writing, a form of expression than a simple medium. It is also, of course, a pretext to discover the world, to seize a few fragments of it to testify a posteriori.

If he is willing to travel the world to bring back images of it, if he is more willing to operate in Naples, Tokyo or, here, Laos, we could not call Yvon Lambert’s work a “travel photography”. Or else, it should be admitted that travel is more a state of mind than a quest for exoticism. No matter the destinations, the kilometers covered, only the desire for uprooting matters. His view of things clearly prevails over the things themselves. And the suggestion always prevails over the affirmation or demonstration.

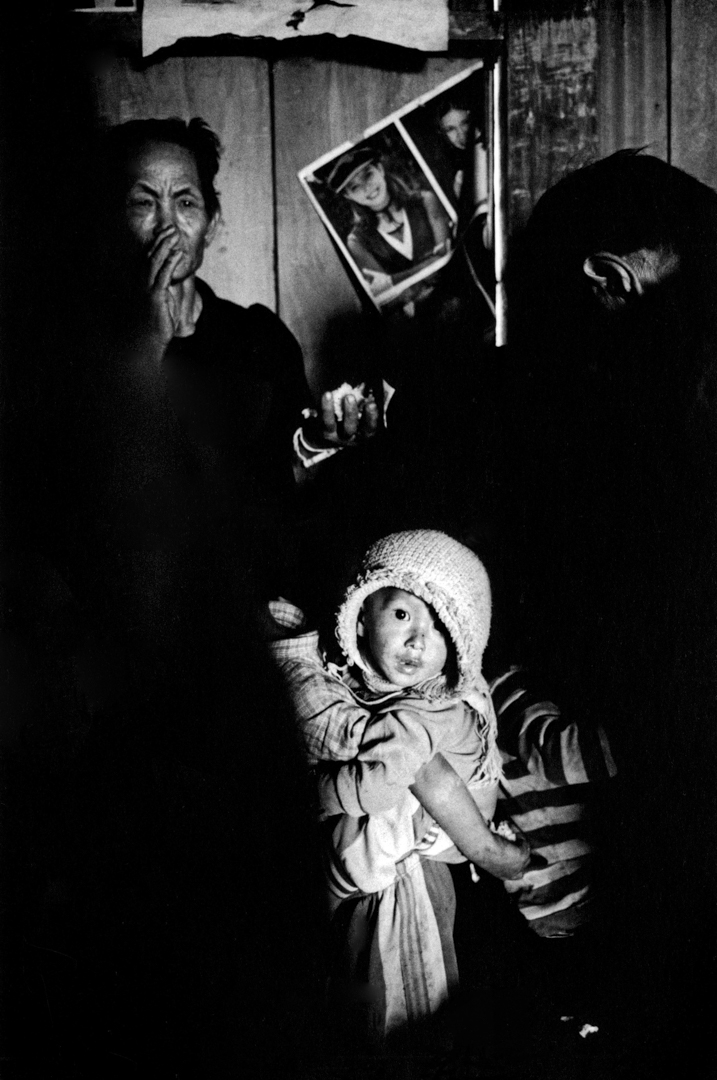

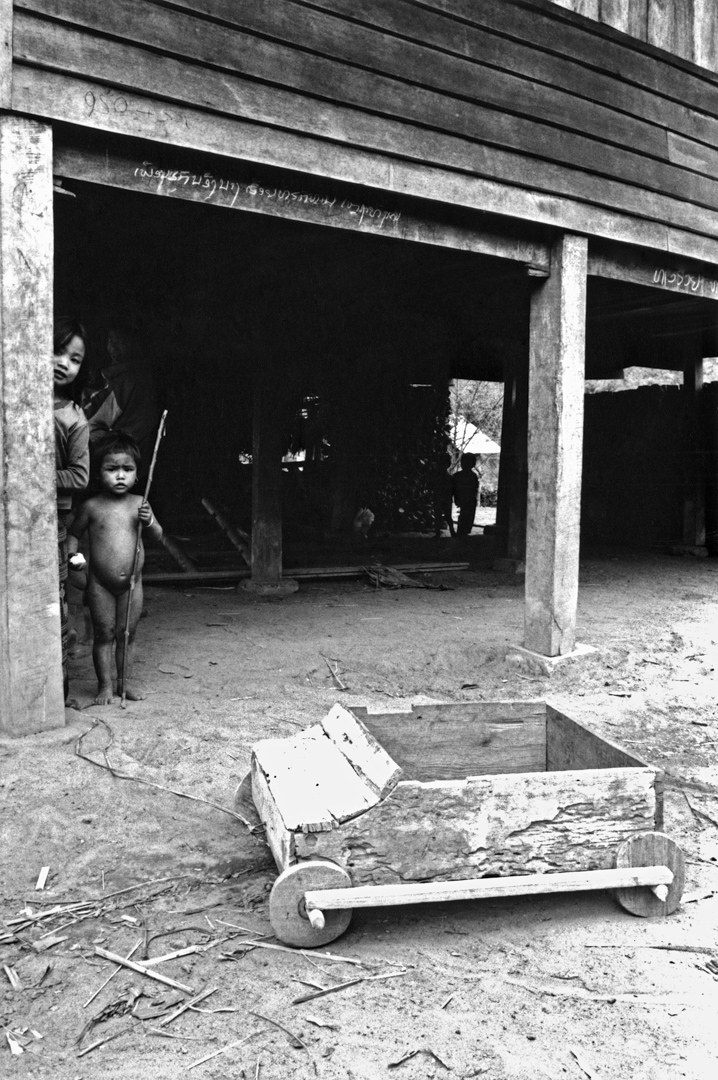

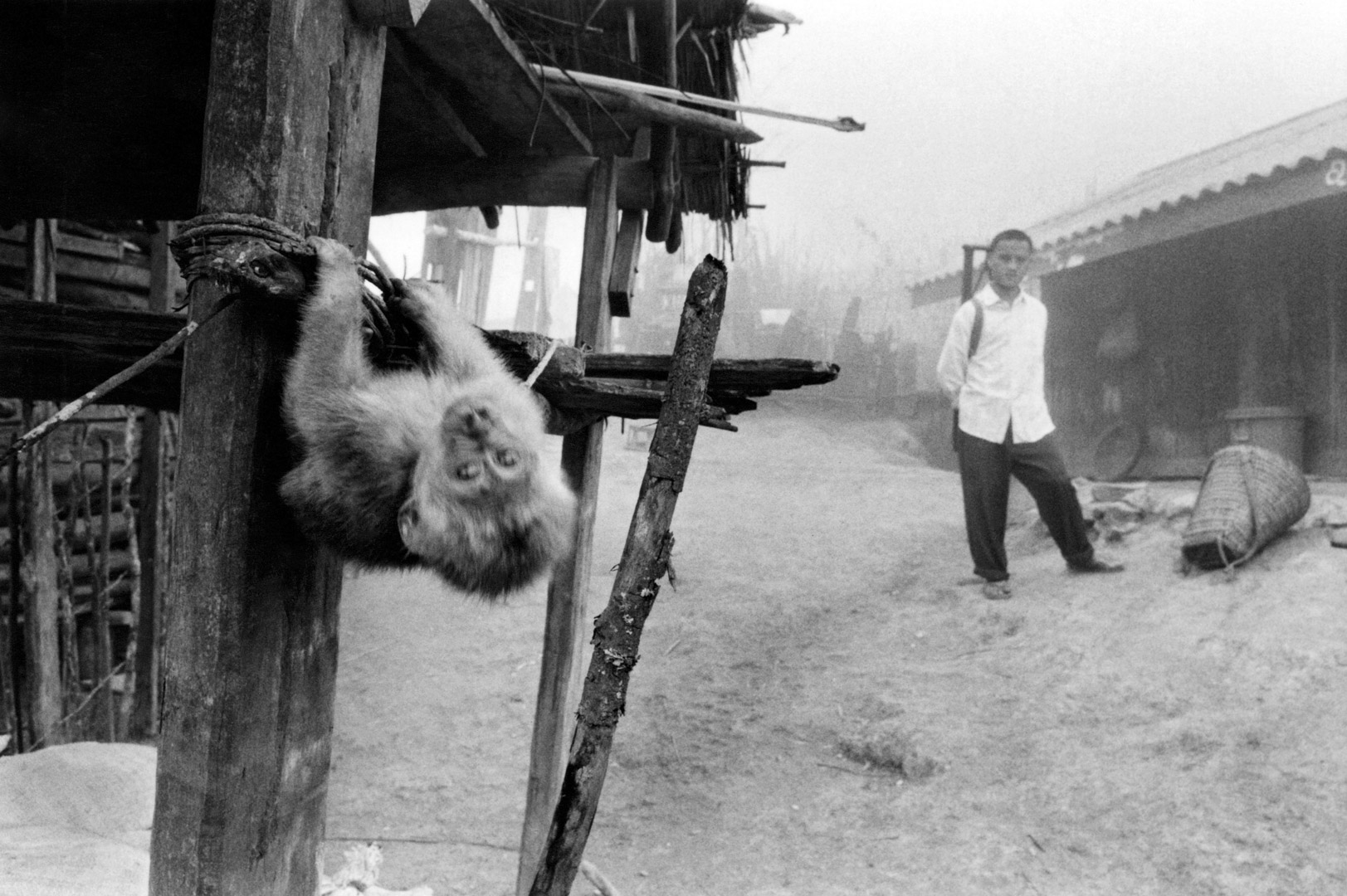

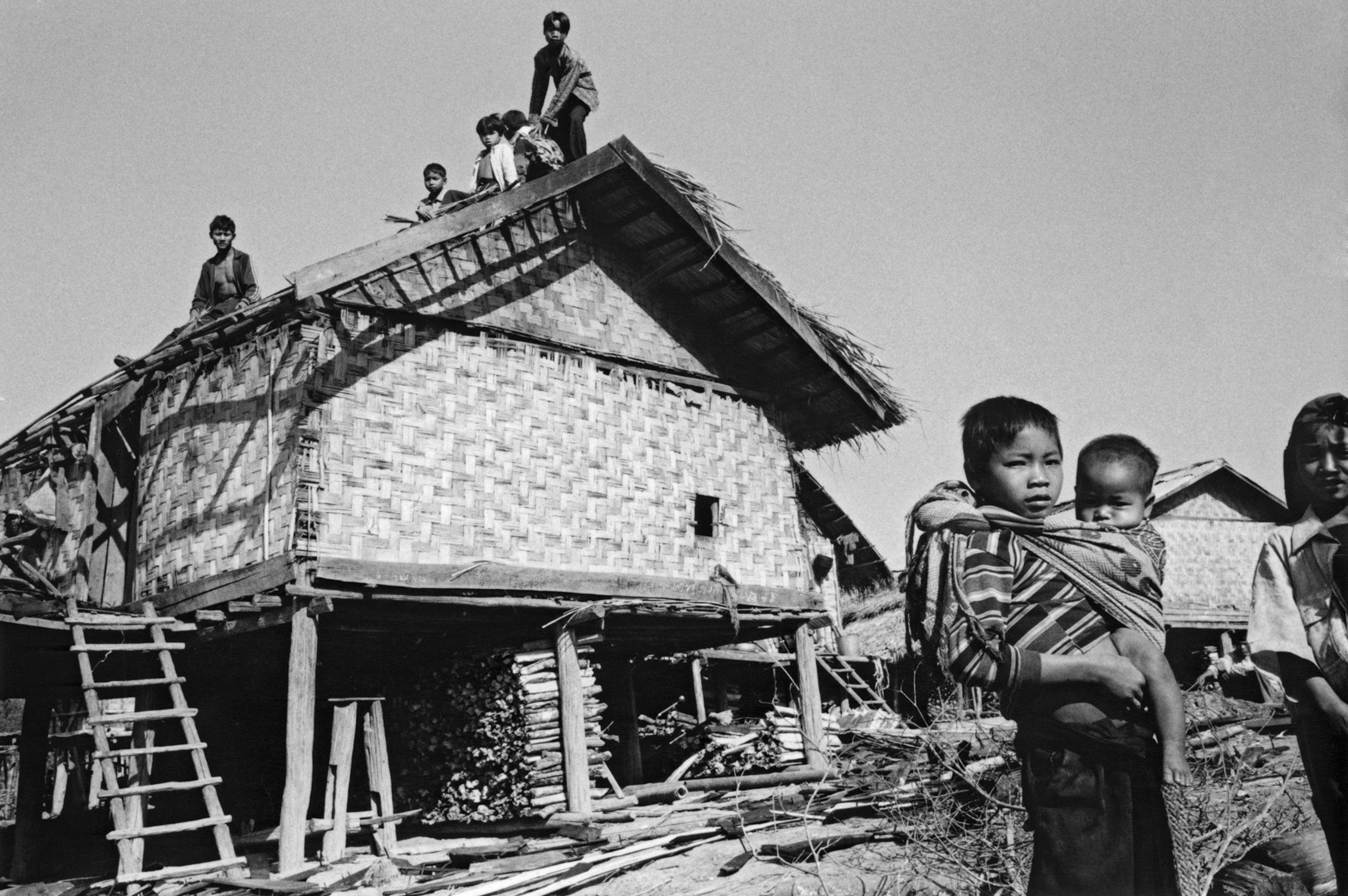

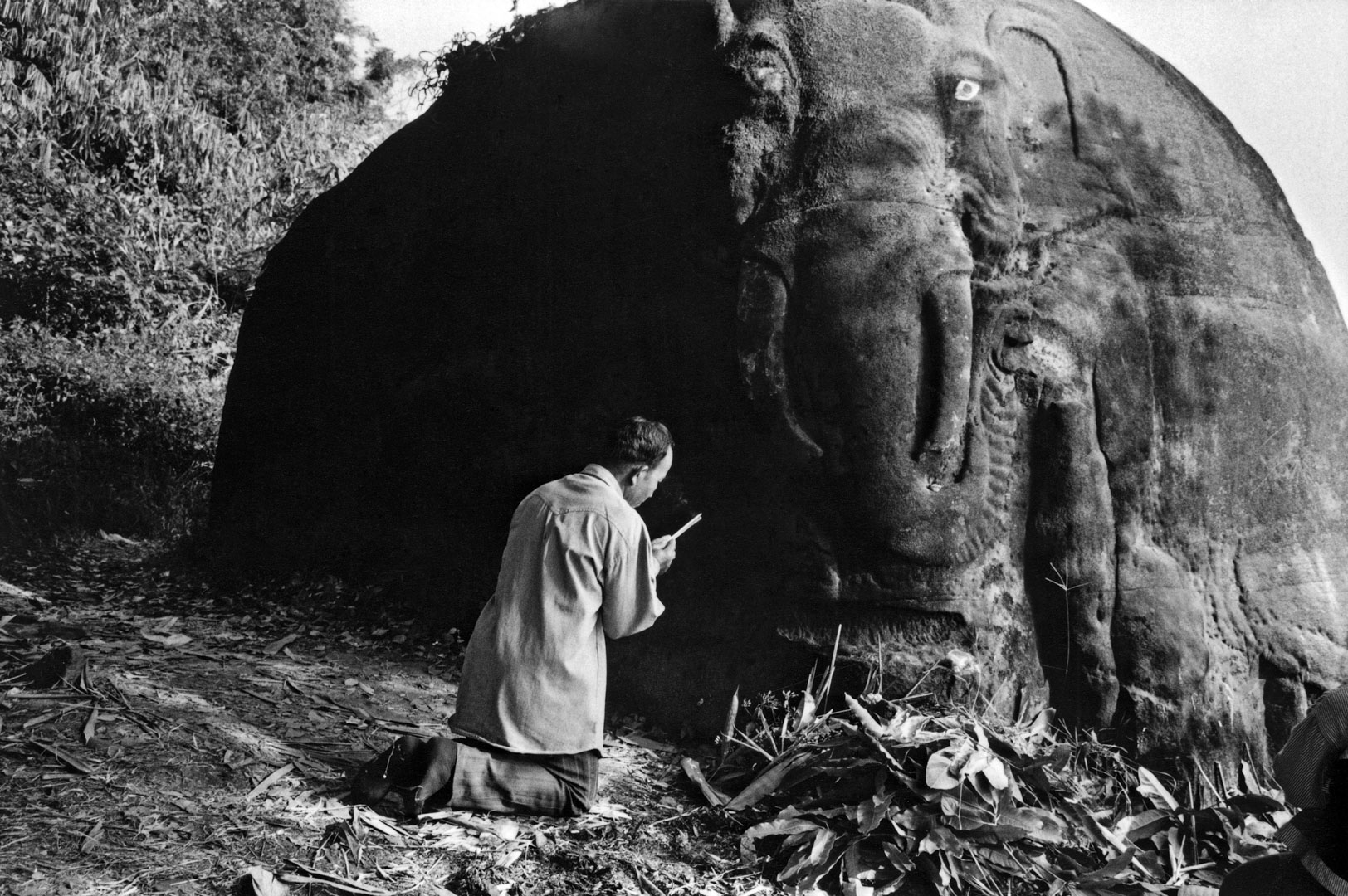

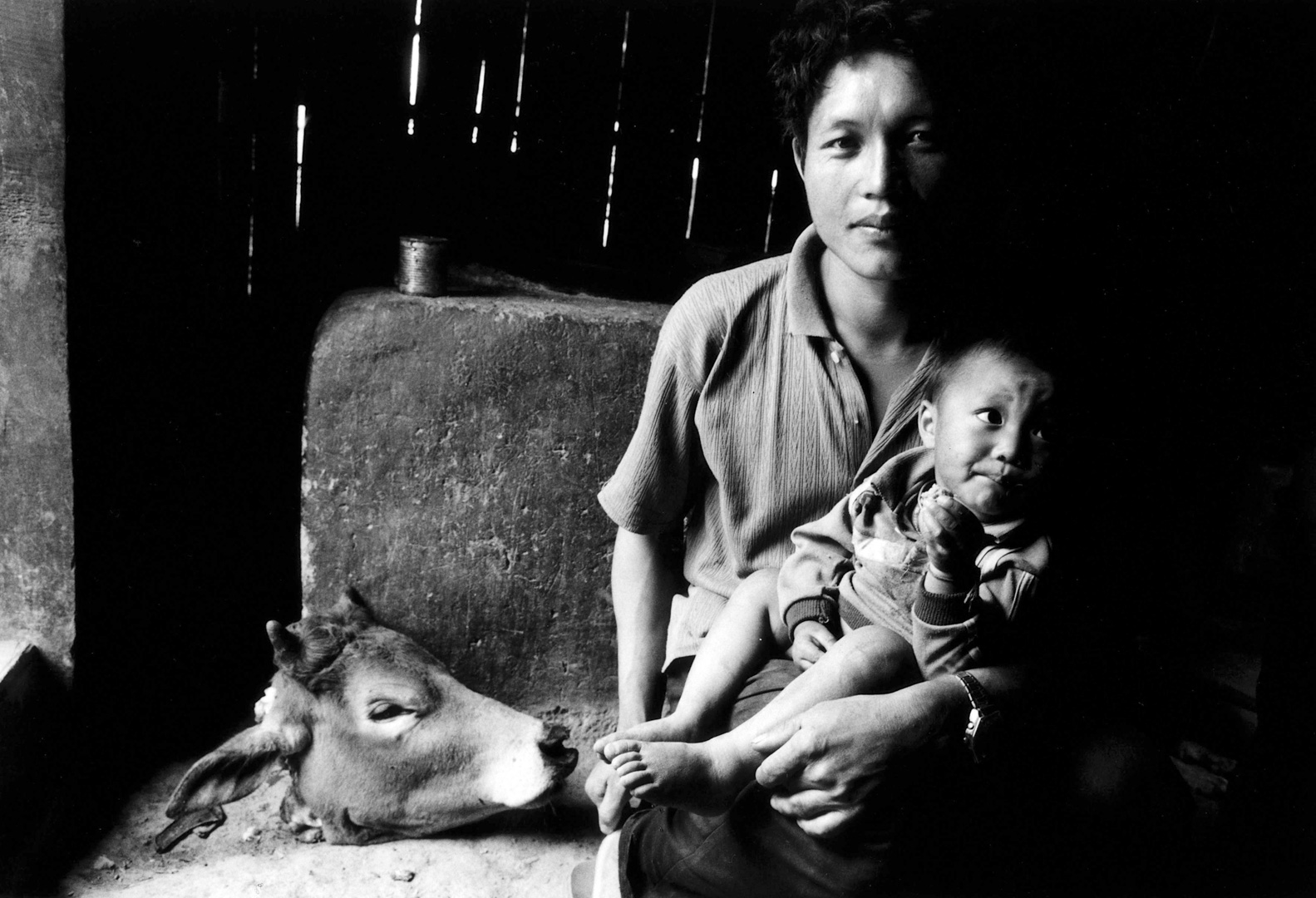

What the photographer brought back from his Laotian journey is the opposite of the icy pages of tourist brochures. Even when historical, cultural, social or political realities appear only in the background, when they are more evoked than stated, they are present and reflect the situation of a country in full change, emerging from its isolation and opening up a little more to modernity every day while remaining confronted with internal divisions and the difficulty of preserving its identity.

Buddha statues, haloed with radiant light, stand next to a traffic accident. In the early morning, monks perform their daily procession, arousing the generosity of the faithful, while teenagers in love are just a stone’s throw away, kissing each other over a state-of-the-art moped.

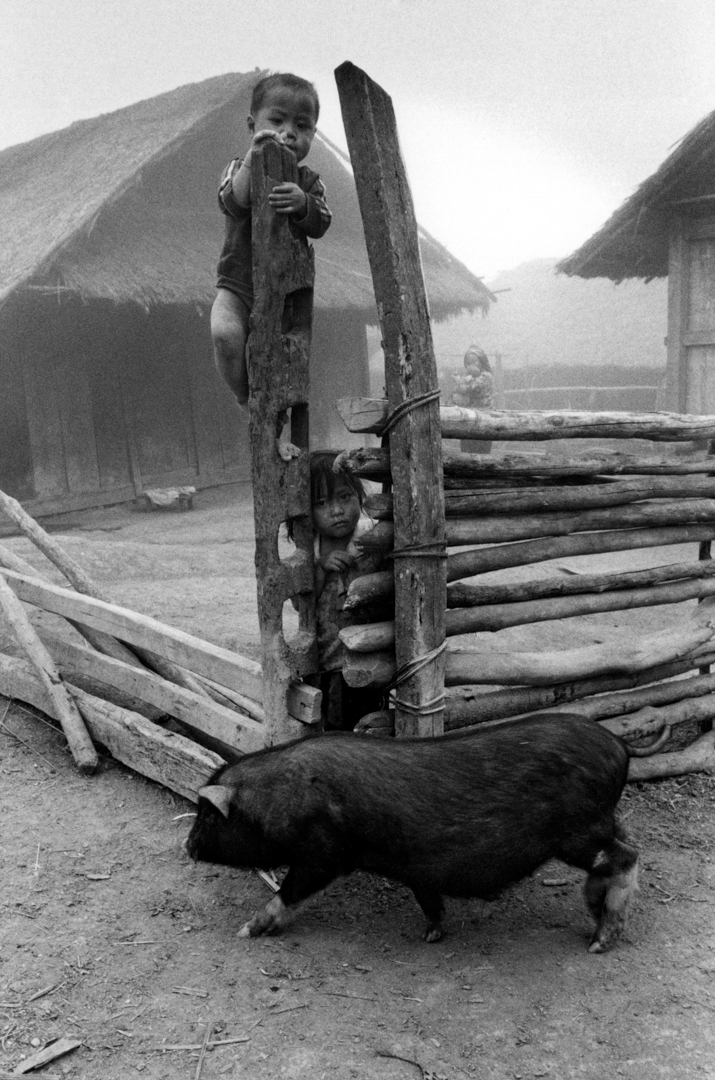

Even if Laos is making great strides on the roads dotted with the pitfalls of globalization, notwithstanding tourism that now places it on the map of an unlikely global village, it continues to be threshed by throwing rice into the air and falling into a basket held at arm’s length. Silk is still spun in Akha villages, as it has always been done. In Hmong villages, artificial paradises are reached by smoking the opium that has been cultivated, as has been done from generation to generation since time immemorial.

Secular gestures and traditions attempt to delay the inexorable march of time. Disregarding so-called modernity and so-called progress, everyday life seems immutable, governed only by the essential laws of the universe.

There is a clammy slowness in Yvon Lambert’s photographs, as if he too had succumbed to the rhythm imposed by the waters of the Mekong, a river of legend, source of life and mystery.

When practiced with this rigour and generosity, documentary photography remains a unique and indispensable way of understanding the world. It is said to be from another age, anachronistic, moribund. It has been said for so long that there is no longer any reason to worry about the threat. She is alive and well, and Yvon Lambert provides one of the many proofs.

Alain D’Hooghe