L’explication, la paix, l’oubli, 2015

Lise Sarfati taught me to photograph slowly; Nicolas Bouvier, to travel slowly. With them, I discovered the freedom of rigour, the sovereignty of obsession, the concision of gesture.

I’ve always found travel to be explicable, following a nomadic meander in the sedentary course of things; other places, other people; vertigo, then return. And, I would add, the headiness of sharing another person’s everyday life. Arriving at a place for pleasure, I want to be there with honesty. I want something to happen that doesn’t just mean nothing. I want the person’s everyday experience to coincide with that break from my sedentary experience that I call “travel”.

At a certain point, photography, as a language for thinking about the World, became organised according to codes which for a long time I breached only with reluctance: frontality, orthogonality, symmetry, maximum depth of field, natural light, a small rangefinder, a thirty-five millimetre lens, and the fact of photographing human beings only after a period of shared existence, with a long exposure time, using a tripod, at a distance that allowed me to inscribe them in a familiar space, integrating images of mundane details into portraits…

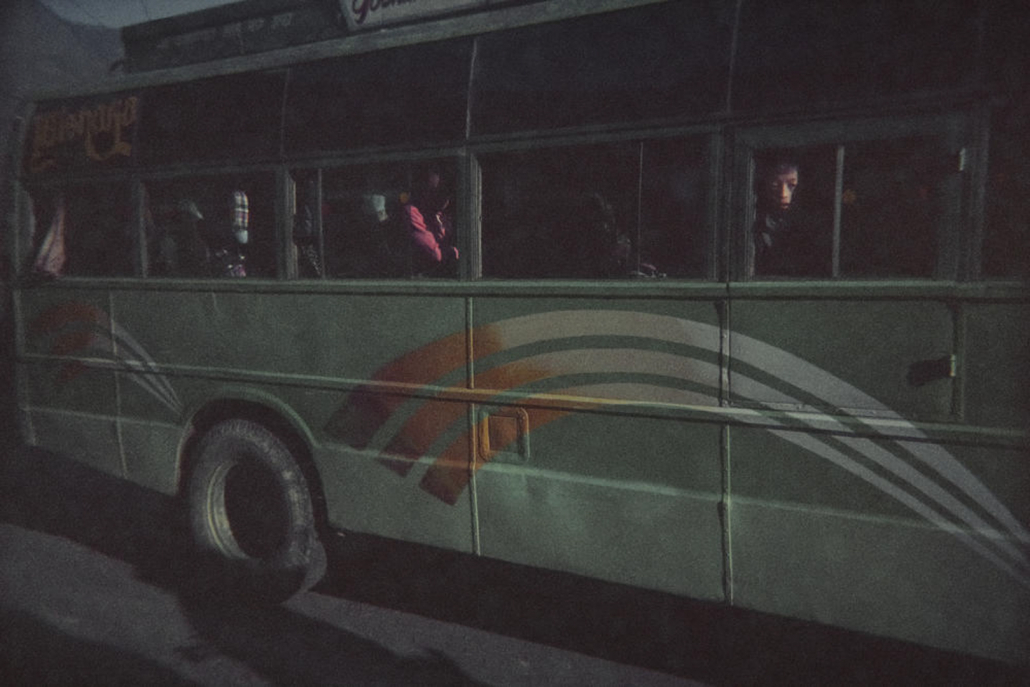

At the start of 2013 I set off for Gatlang, in the Rasuwa district – a village I didn’t know. A friend had told me about the landscapes, the seasons, the plank-roofed houses, the prettily-worked windows, the sacred lake, the cheese plant, human affairs, the courtyards, the marriages and funerals, the passage of the days… I went off for a look.

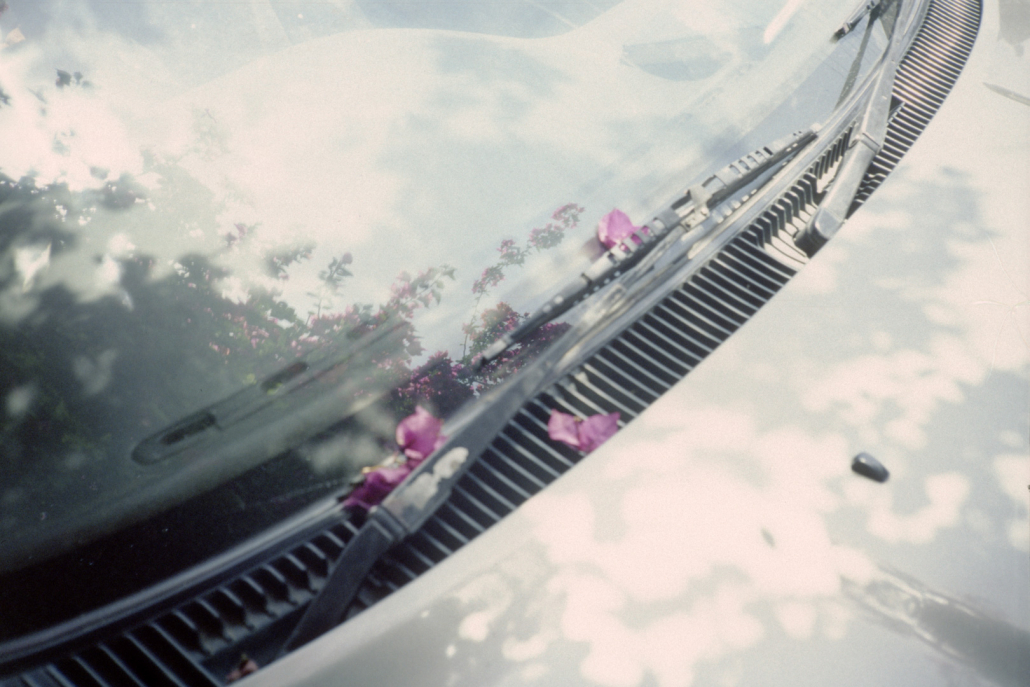

In Gatlang, I had a sense that my modus operandi was being distorted, in terms of both travel and photography. Some months later, once again in Gatlang on a visit to friends, disturbed by this feeling, and hoping, if possible, to get over it, I forced myself to demystify the codes and, rather than travel, to live. I had a small camera that was unusual, spontaneous, “poor”, imprecise. I also had a few free days in front of me. I took some pictures, but without constraint or formalism. My relation to the country, with the camera between it and me, underwent a change. Giving up protocols and procedures made photographing Nepal both more diaphanous and more dense. The gesture lost its solemnity. It rejoined the simple, banal course of life, as close as it could’ve been to walking or breathing. It may have been a question of the instrument itself.

And once the surprise resulting from the change of camera has dissipated, I hope it’ll turn out that the question is above all one of presence and freedom.

Frédéric Lecloux