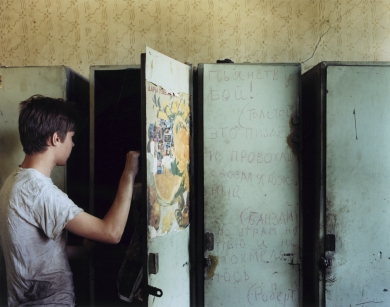

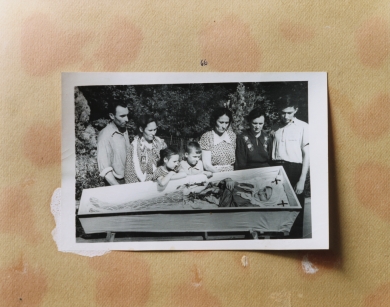

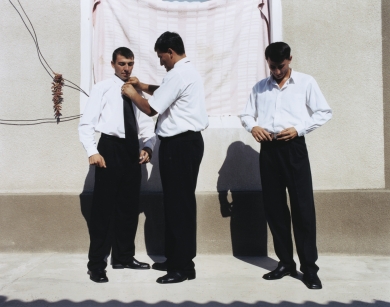

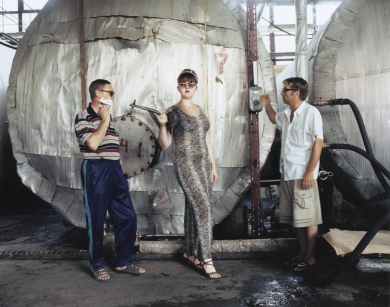

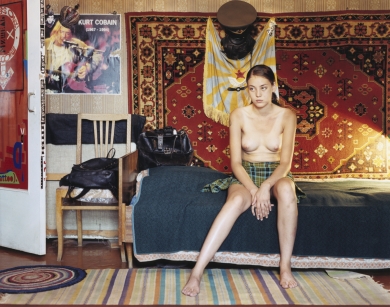

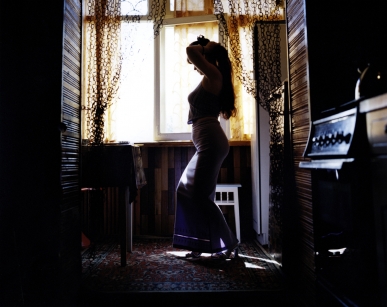

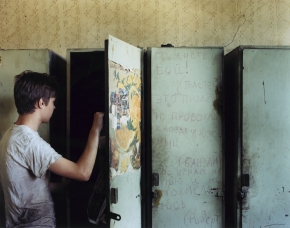

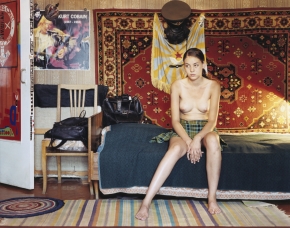

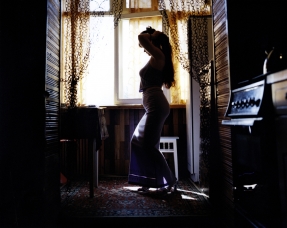

Home & Away, Uzbekistan, 2002

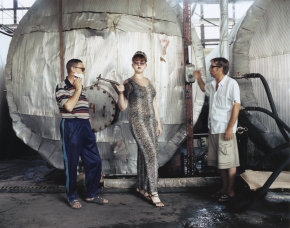

Uzbekistan is a Soviet invention. Before the Russian Revolution of 1917, Uzbeks usually identified themselves ethnically as either nomad or sart (settled), as Turk or Persian, as simply Muslim or by their clan. Later separate nationalities were identified by Soviet scholars as ordered by Stalin. Distinct, carefully crafted traditions were formulated and parceled out to each of these nationalities, mostly to prevent any pan-Islamic or pan-Turkic tendencies.

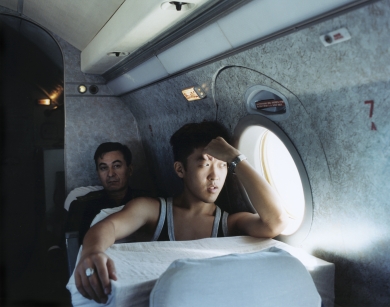

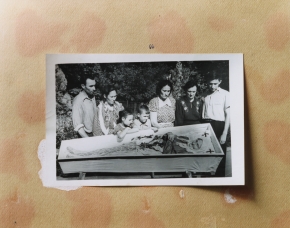

Soviet authorities openly considered Uzbekistan as being a black hole into which they could conveniently dump entire populations considered as being a potential danger to the Republic. The Slavs and other non-Central Asian groups reached Uzbekistan in several waves; chiefly as industrial workers from the 1930’s onwards, political prisoners from the 1930′ to 1950’s (many of these stayed on if they survived), and entire populations deported before or during World War II because Stalin feared they would collaborate with the enemy. The latter included German’s from the Volga region, Ukraine and elsewhere; Ingush, Karachay, Balkar, Chechens, Meskheti Turks and Kalmyks from the Caucasus region; Crimean Tatars; and Koreans from areas of Russia bordering Korea. Many died on the way to Uzbekistan or soon after arriving.

Today, while Uzbekistan is secular with a determined separation between religion and state, it is decidedly not democratic. The figure whose influence has stretched from municipal gardener’s salaries to gold production quotas, even prior to the independence, is President Islam Karimov.

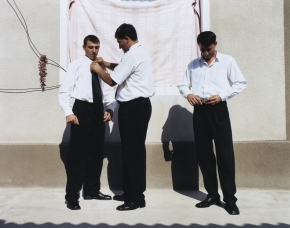

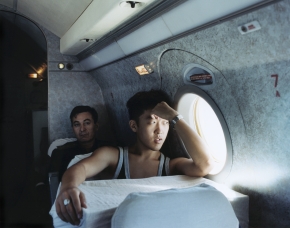

Trends towards pluralism which are increasingly evident in other Central Asian republics are absent here. Due to the current economic and political situation, and rising aggravation as political and administrative power is falling into the hands of local people, many members of the 20 minority ethnic groups that constitute Uzbekistan are emigrating, leaving for their so-called homelands. Of the 2,600,000 Slav population (Ukrainian / Russian / Belarussian), 60,000 emigrate every year. Some have returned to Uzbekistan, either disillusioned with life in their country of origin or reaffirmed in the knowledge that Central Asia is their home, like it or not. Most of the 200,000 Germans have left for good along with the 3,000 Poles and almost the entire Jewish population. Even the venerable Bukharan Jewish community whose roots date back to the 9th century has left for Israel or New York.

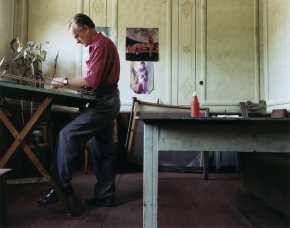

These ethnic groups represent Uzbekistan’s history and identity which the current exodus is steadily draining away. Historically, and perpetuated by the Soviets, each group was identified by the function it fulfilled within Uzbek society: Jews were tanners, Kazaks soldiers, Russians and Ukrainians professionals, Tajiks intellectuals, Karakalpaks and Kyrgyz hunters, Uzbeks farmers and soldiers, Koreans grocers and Germans and Polish engineers. Today, unlike those that left for Australia or America during the 19th century, the non-Uzbeks are now returning to their countries of origin. They leave behind them ghost towns, villages and collective farms inhabited only by the aged and those too poor to leave.