Holding, Arriving, Photographing

Tonnerre, 2017 – 2024

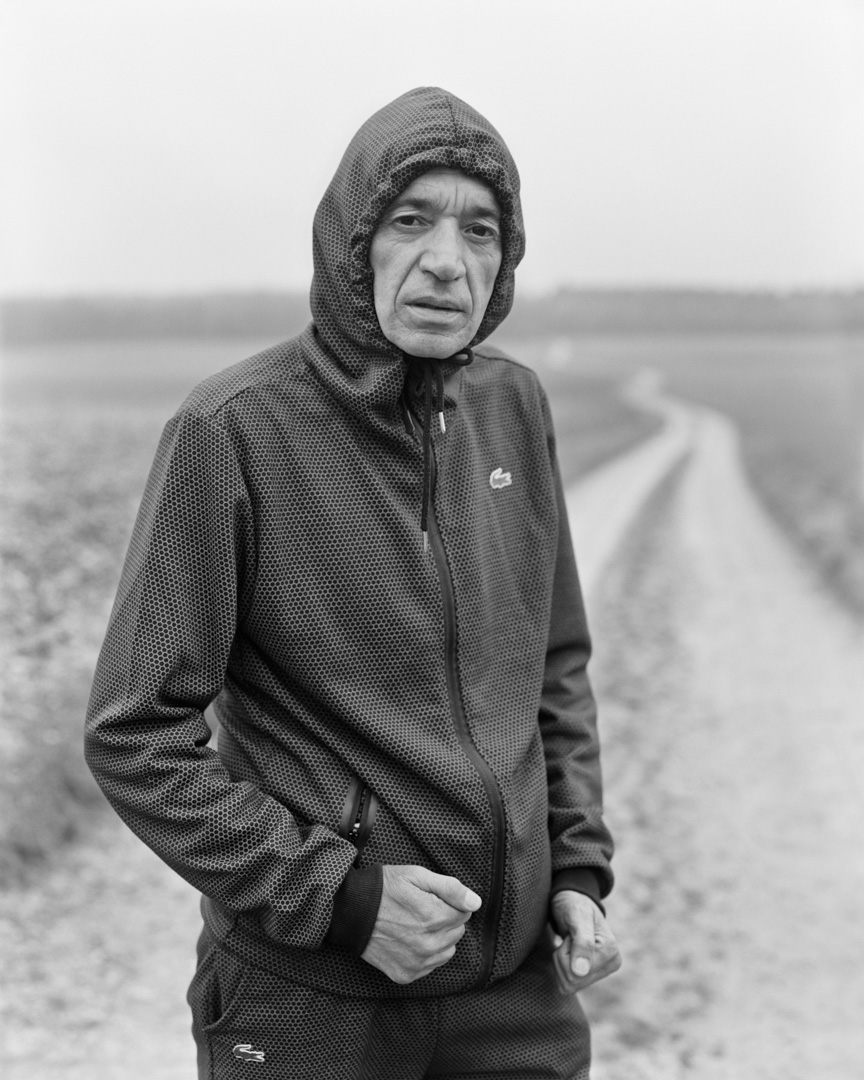

How does it feel for people in precarious situations to be moved to a city they didn’t even know existed?

It was around this question that photographer Jean-Robert Dantou spent seven years, as part of a doctorate in Research-Creation (SACRe – ENS – PSL), carrying out research in documentary photography in a commune on the outskirts of Paris.

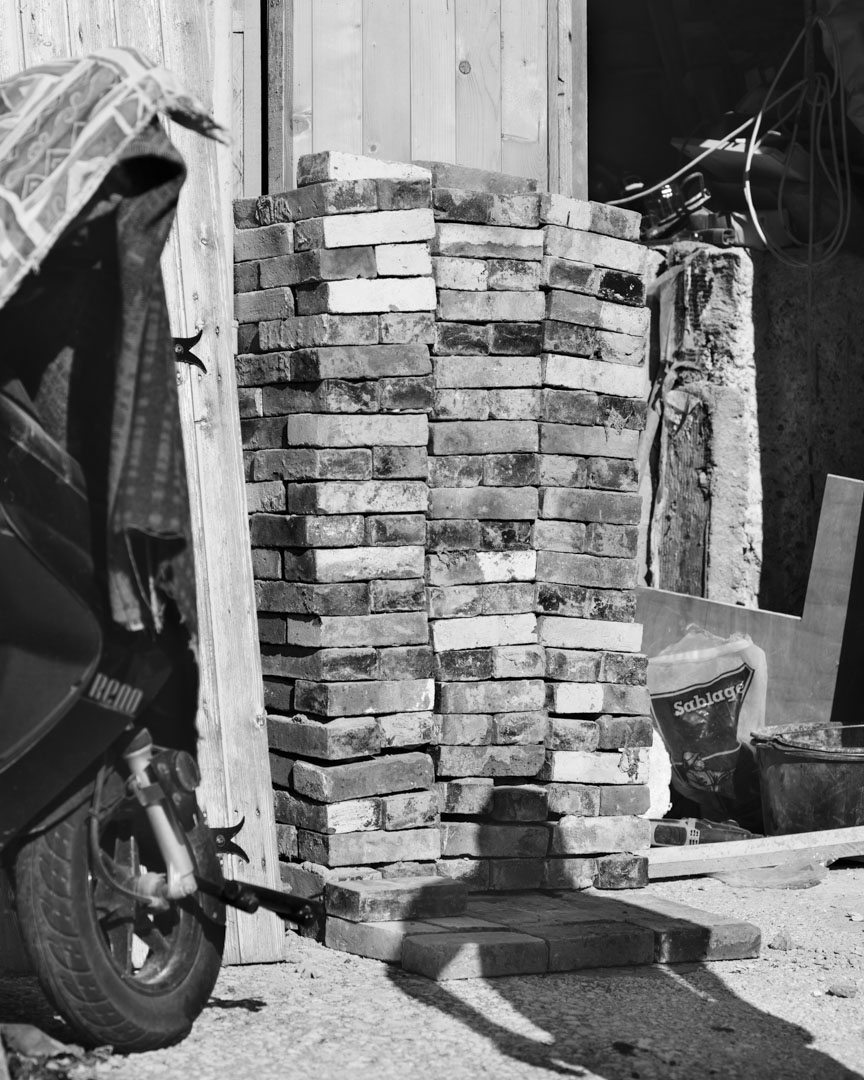

Since the confines of 2020 and 2021, the town of Tonnerre (Yonne) has been experiencing a revival of dynamism, with the arrival of investors in the real estate and training sectors, new shopkeepers, professionals and entrepreneurs working in the fields of art and the social economy. These recent changes bring to a close a period of profound transformation which, since the 2000s, has jeopardized the area’s social, economic and demographic equilibrium. In particular, the commune is confronted with spiraling mechanisms: industrial collapse leads to household impoverishment and the departure of whole sections of the population; the resulting demographic decline is compounded, on a national scale, by policies to close public services; these closures in turn exacerbate the demographic decline and lead to other cascading collapses, affecting town-center businesses for example.

Far from the stereotypes of the timeless stability of rural areas, Tonnerre’s recent history has seen profound changes, notably in the form of significant demographic renewal: more than a third of the town’s inhabitants have lived in Tonnerre for less than five years.

People from all social and geographical backgrounds have arrived in the town in recent years. Some of them arrived without really wanting to: How are these moves organized? Who is behind them? What institutional logic do they follow? What is the degree of constraint exerted on individuals?

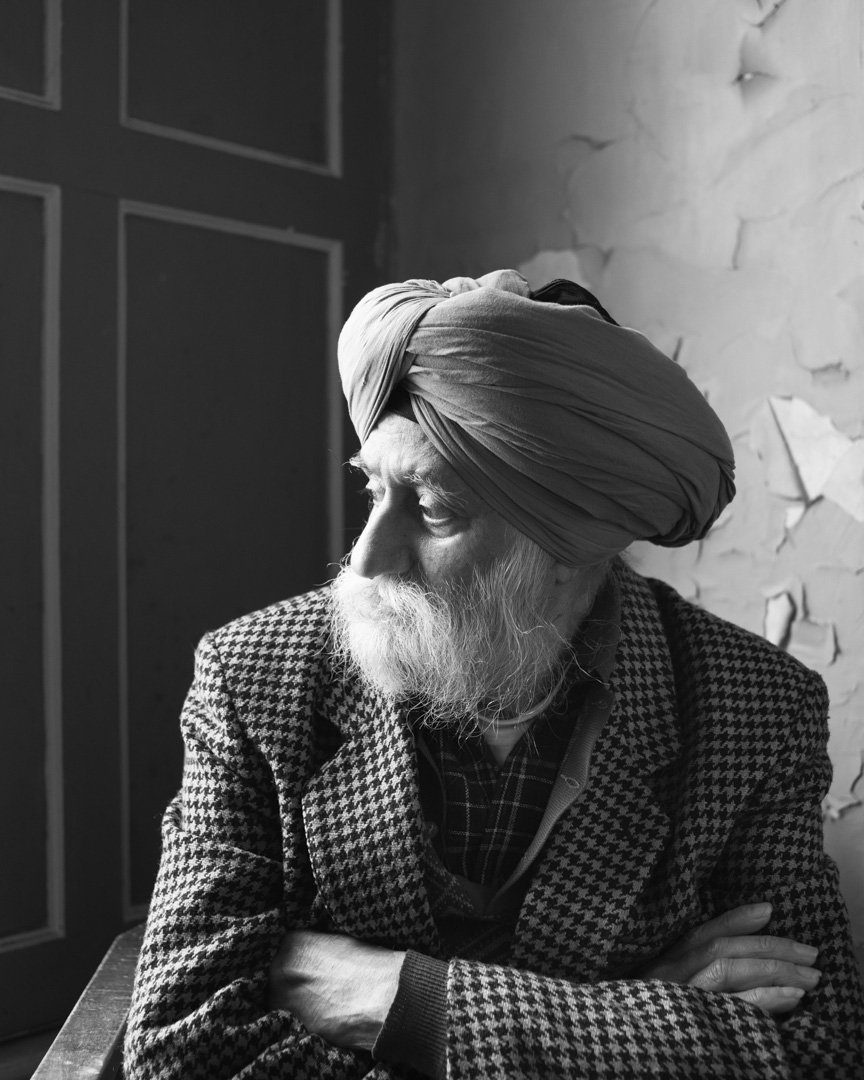

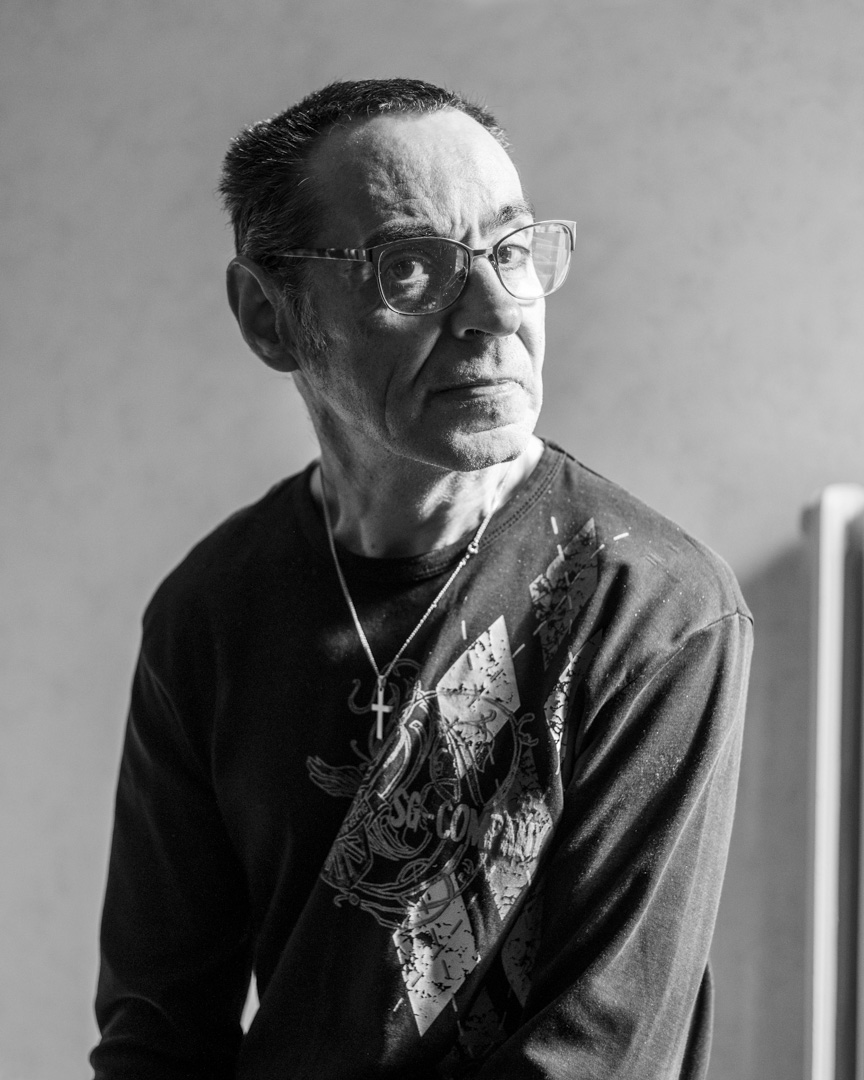

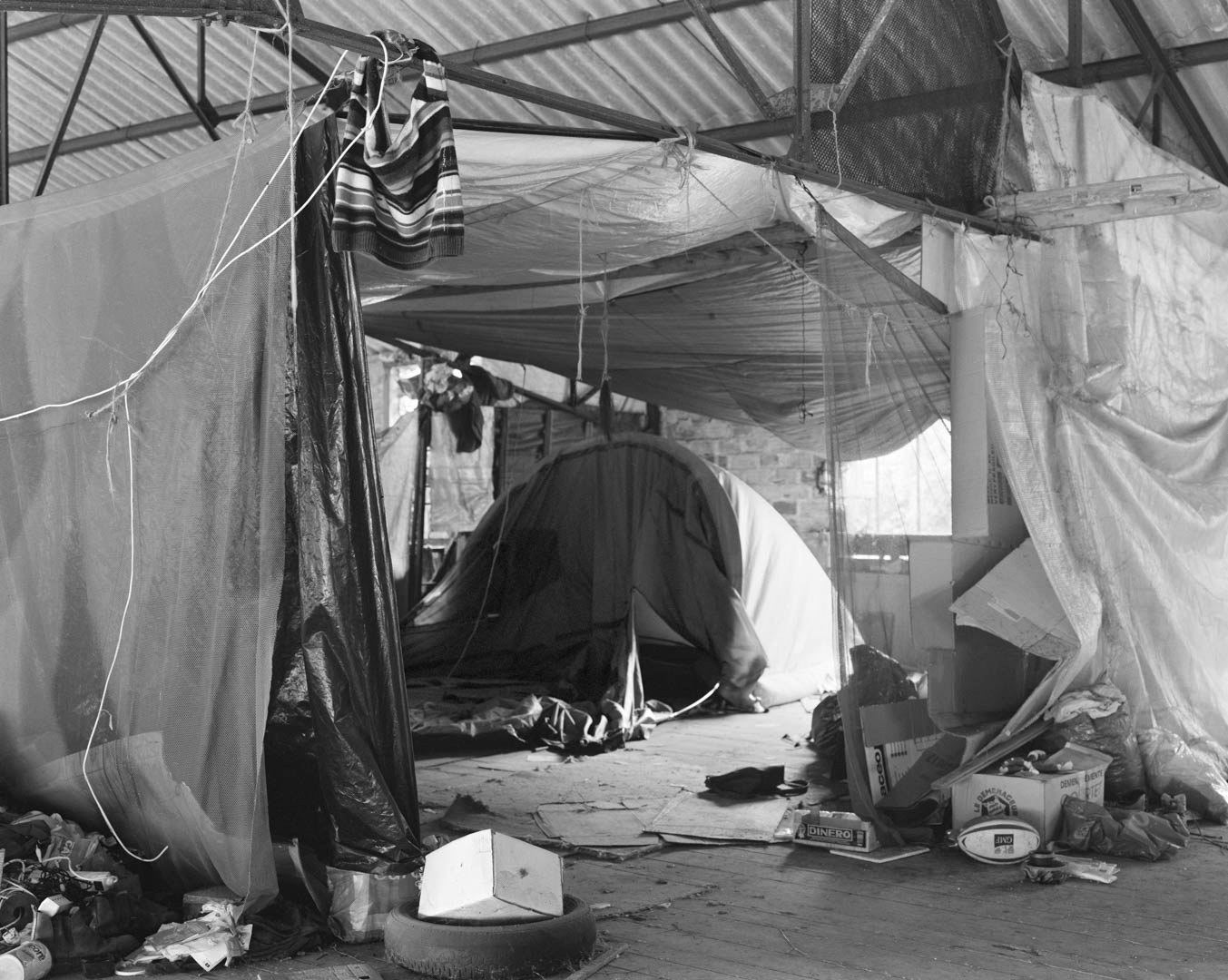

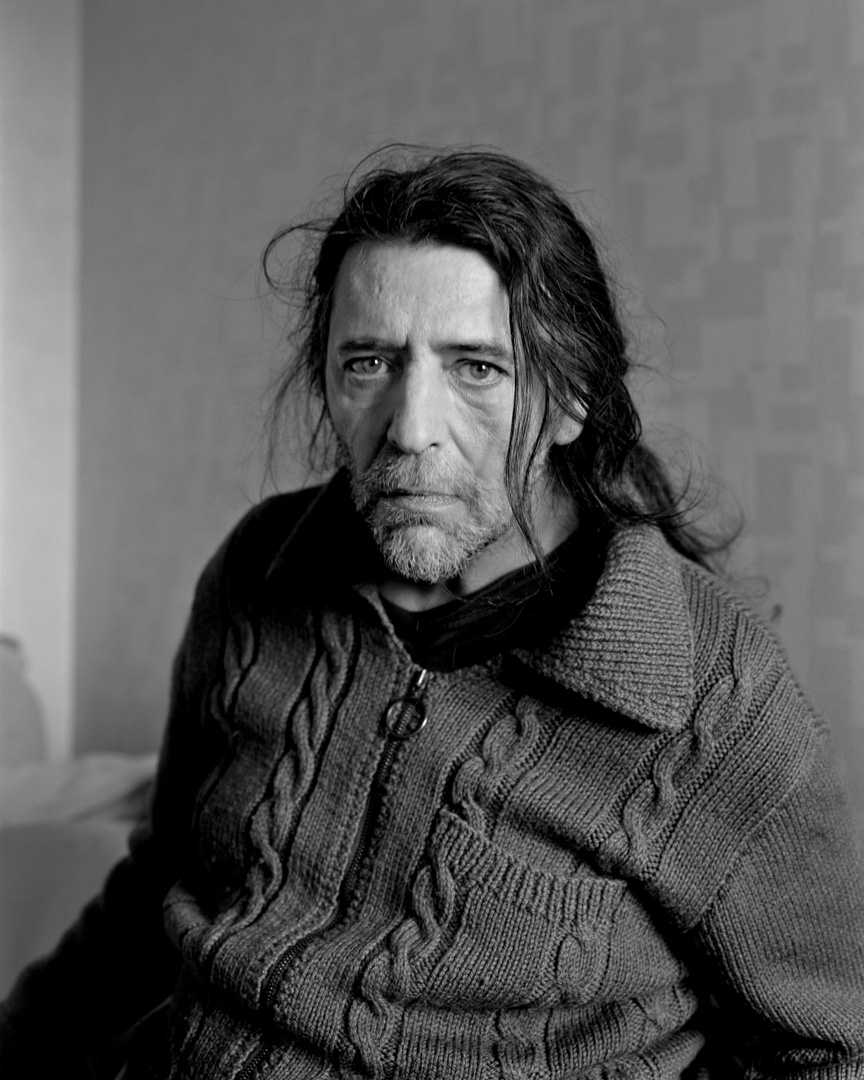

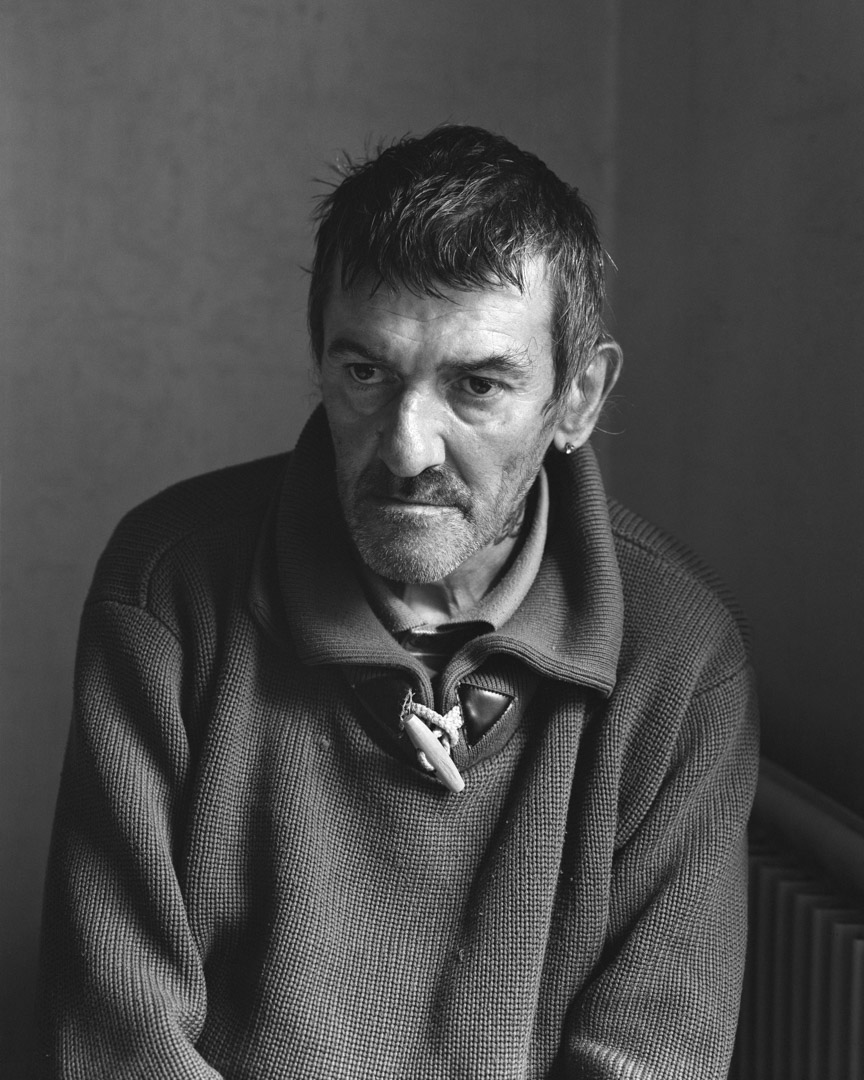

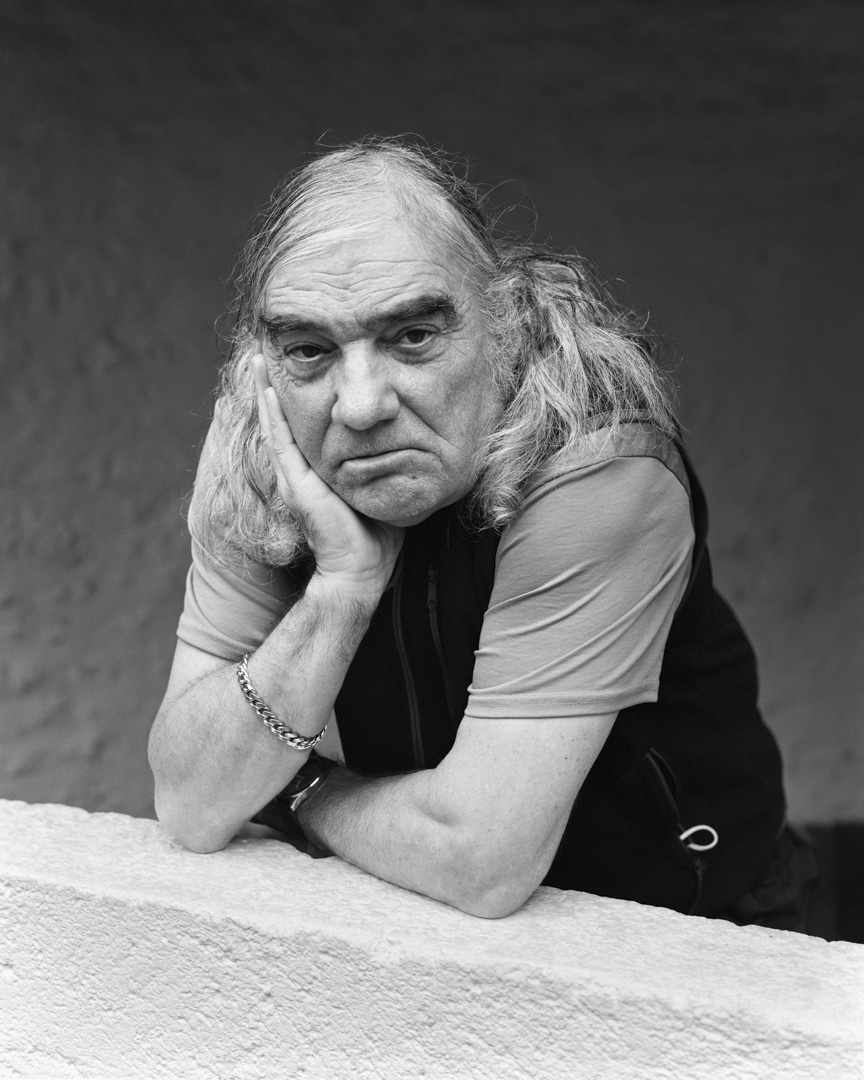

A survey of some forty residents who had recently arrived in the area via precarious routes identified eight “channels”, each with its own logic. Some involve “prescribers”: professionals in the medico-social field who “send” people in situations of great fragility from one area to another. Others take place without prescription: people arrive on their own, informally, with or without a network of acquaintances.

This documentary research is organized around five sets of photographs. The first three are devoted to describing the ways in which precarious people arrive in the city: “Arriving via emergency accommodation”, “Arriving informally”, “Arriving via the Résidence Accueil”. The fourth, entitled “Holding on”, looks at how long-standing residents, who remember the town’s prosperous past, cope with the daily upheavals they face. The fifth and final set offers a methodological treasure hunt: How is a documentary photographic survey constructed? What do the people photographed confide when they lend themselves to a photo shoot? Can photography be a reliable tool in the service of a knowledge enterprise?