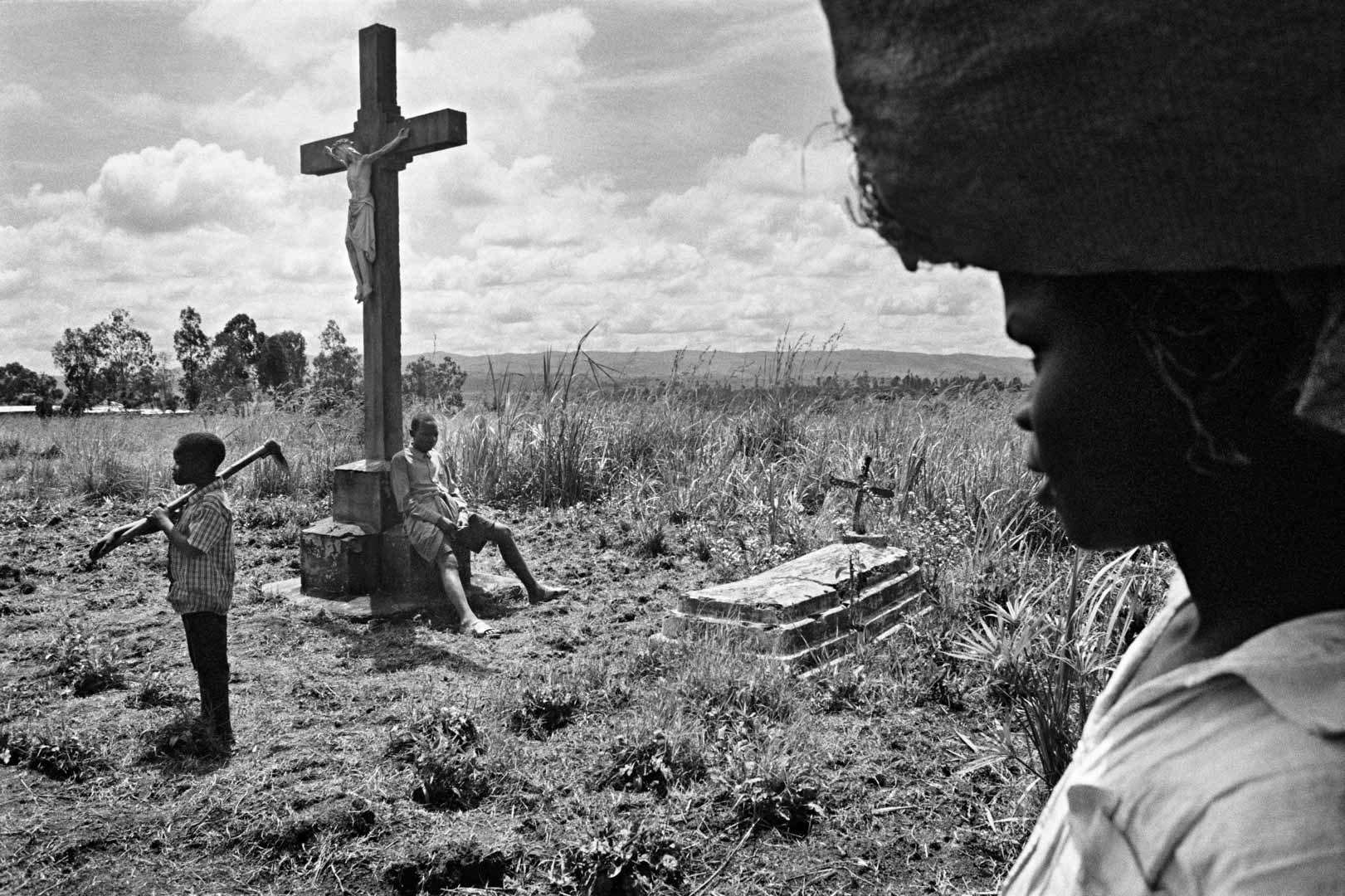

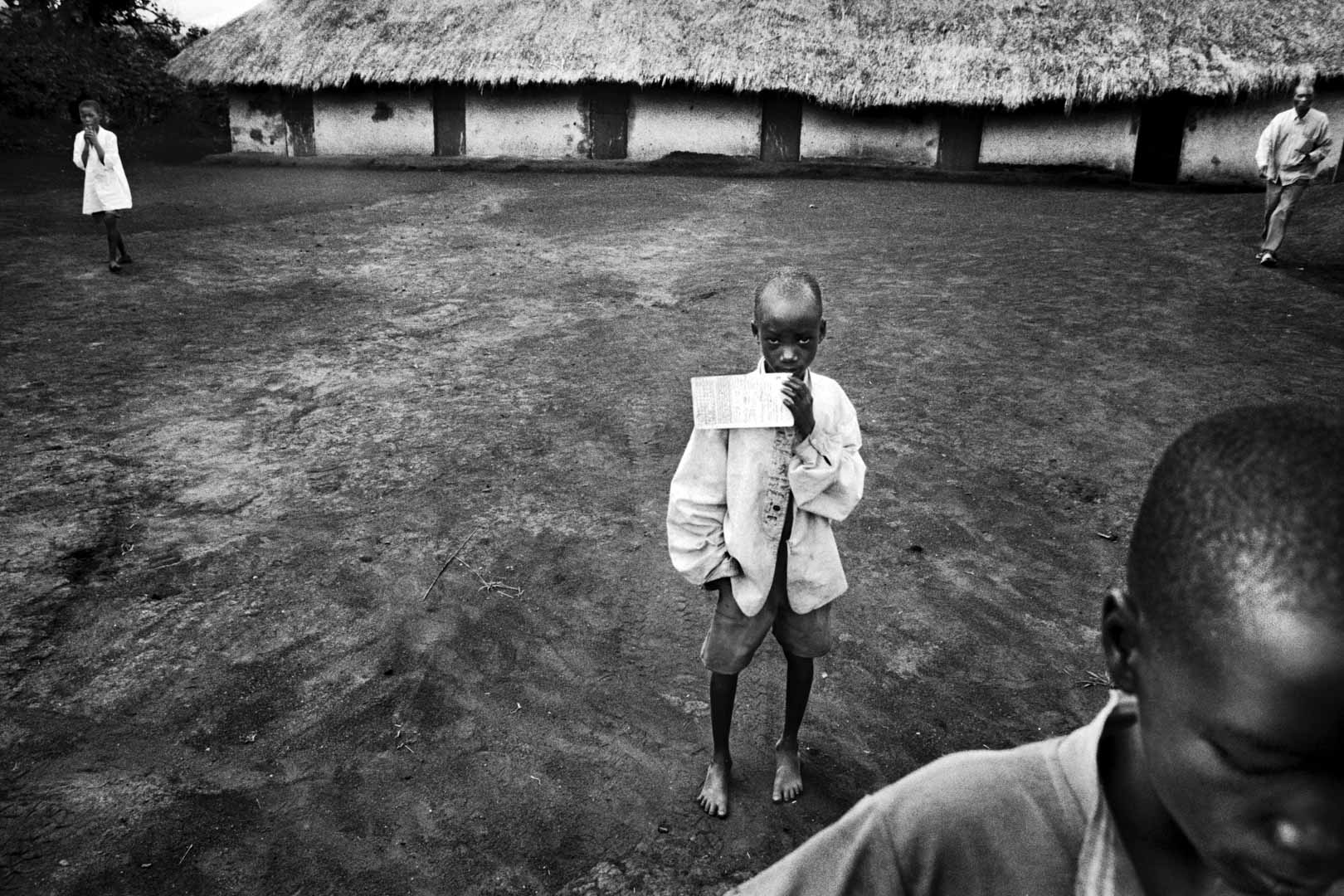

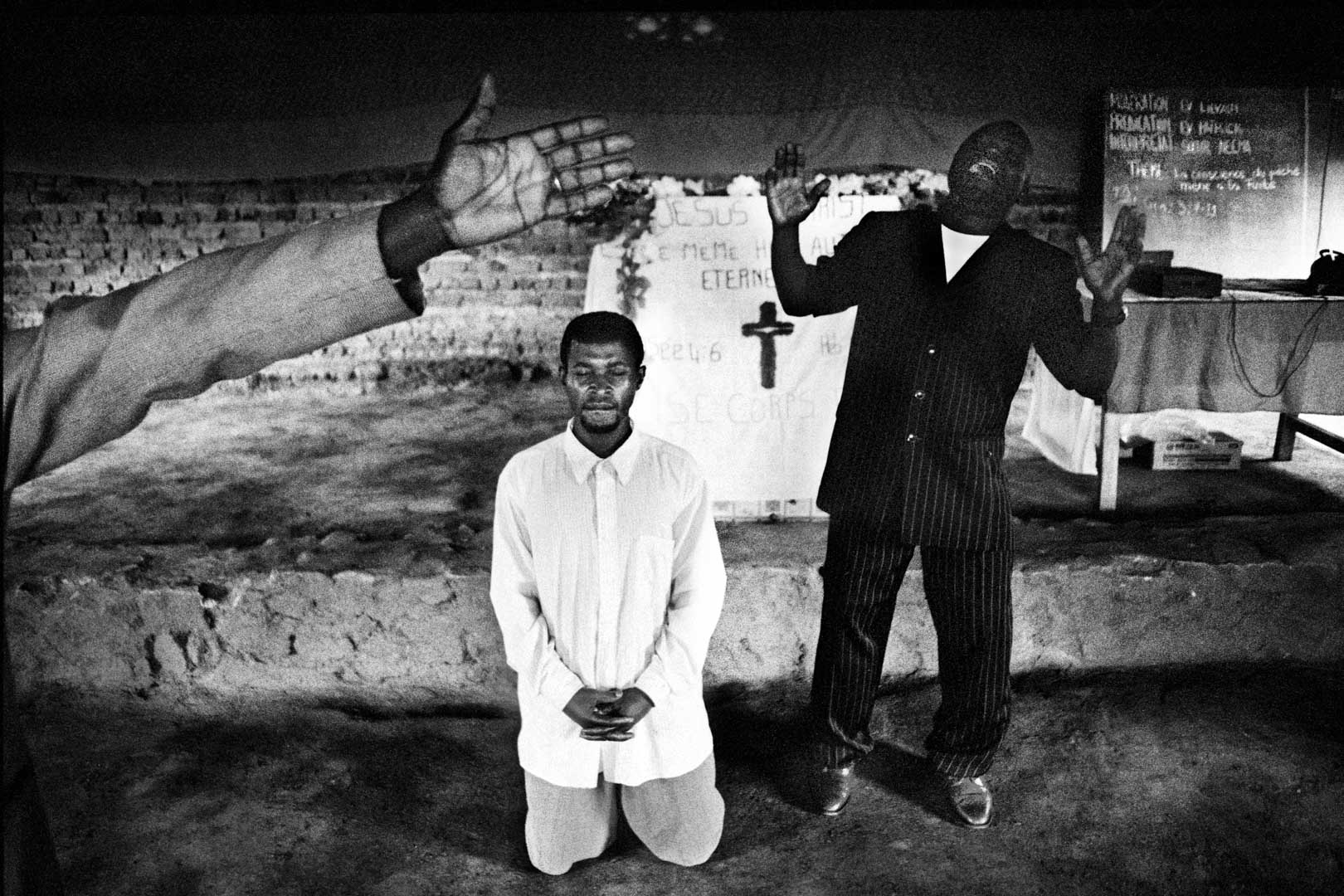

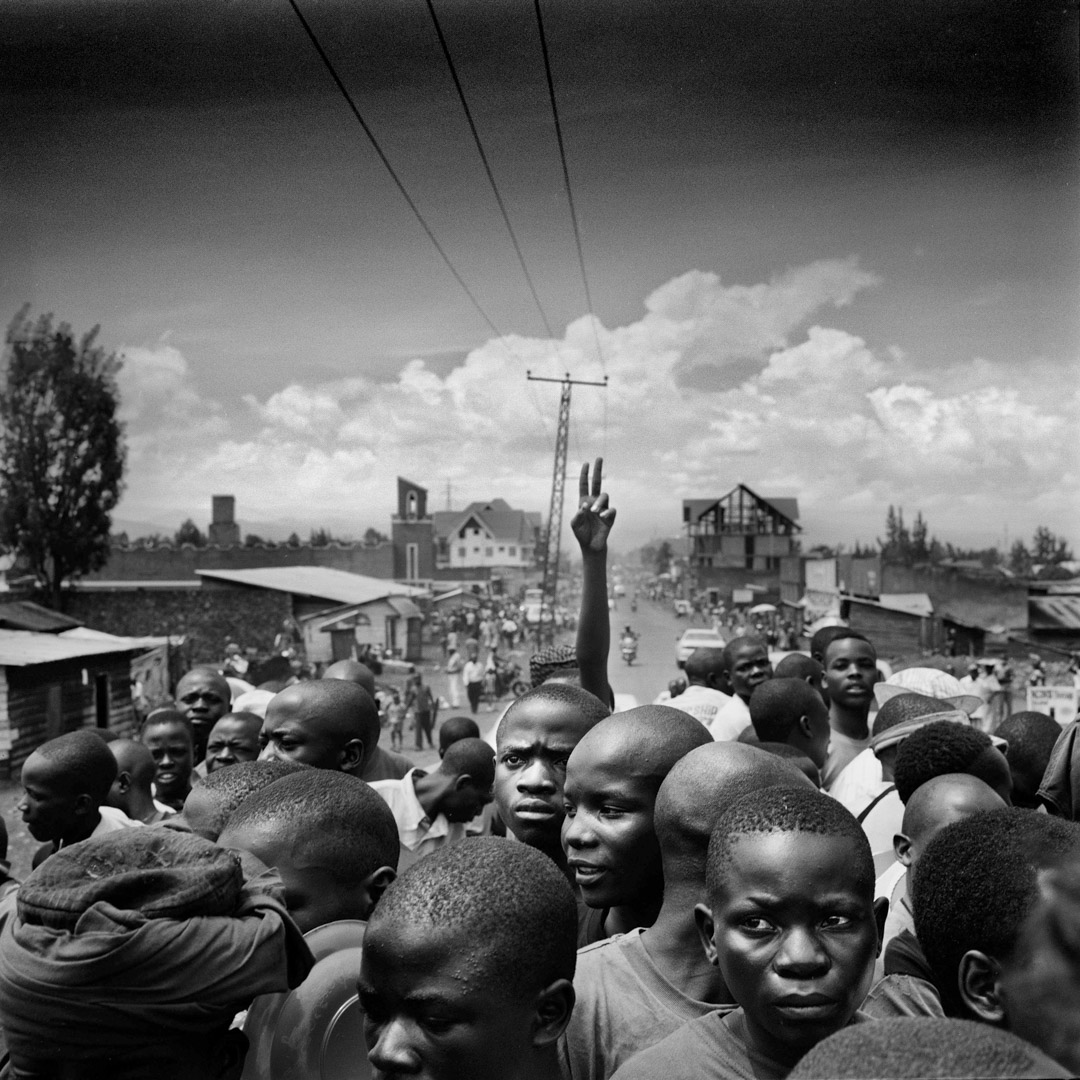

Congo in Limbo, 2007-2010

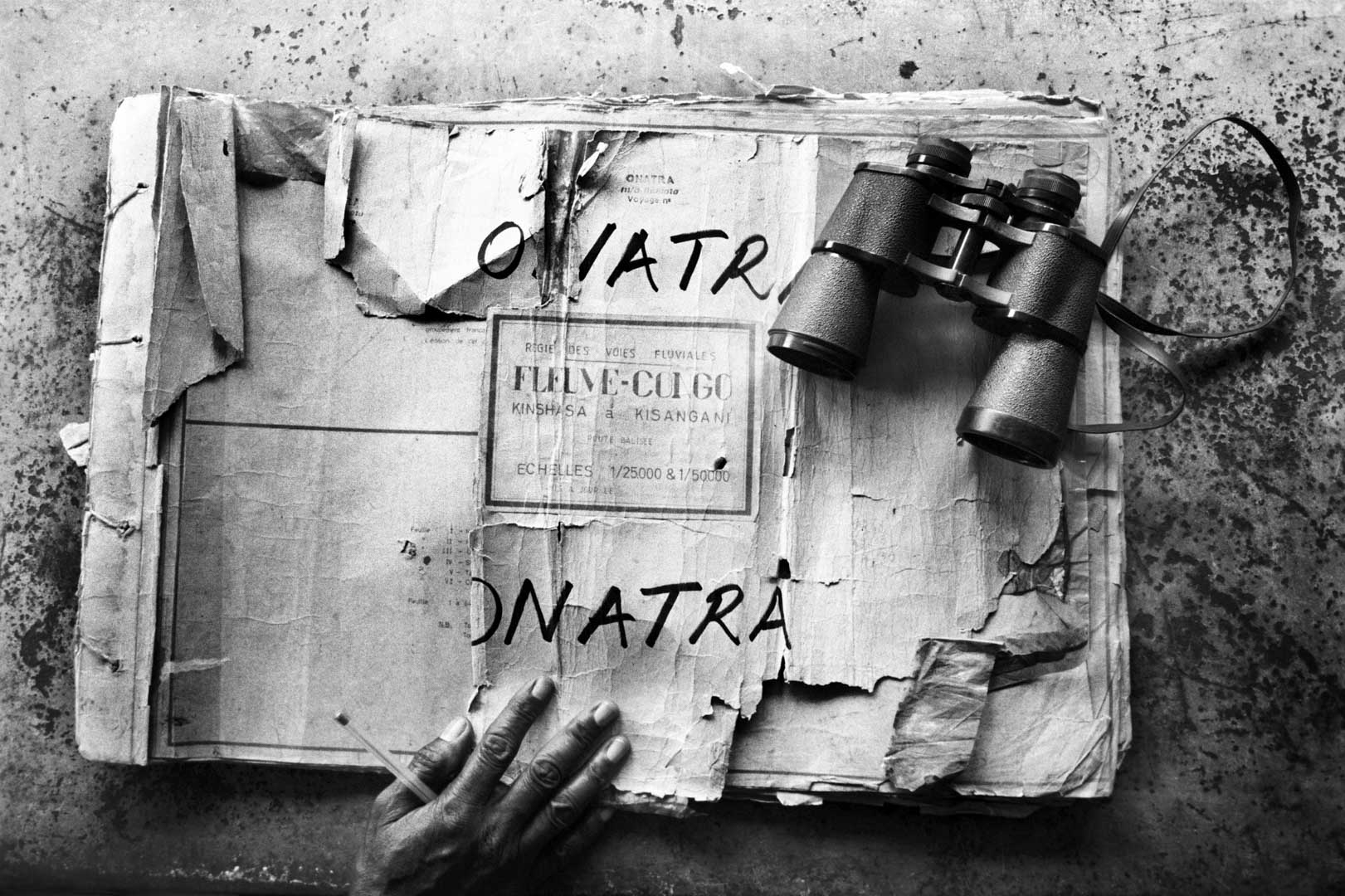

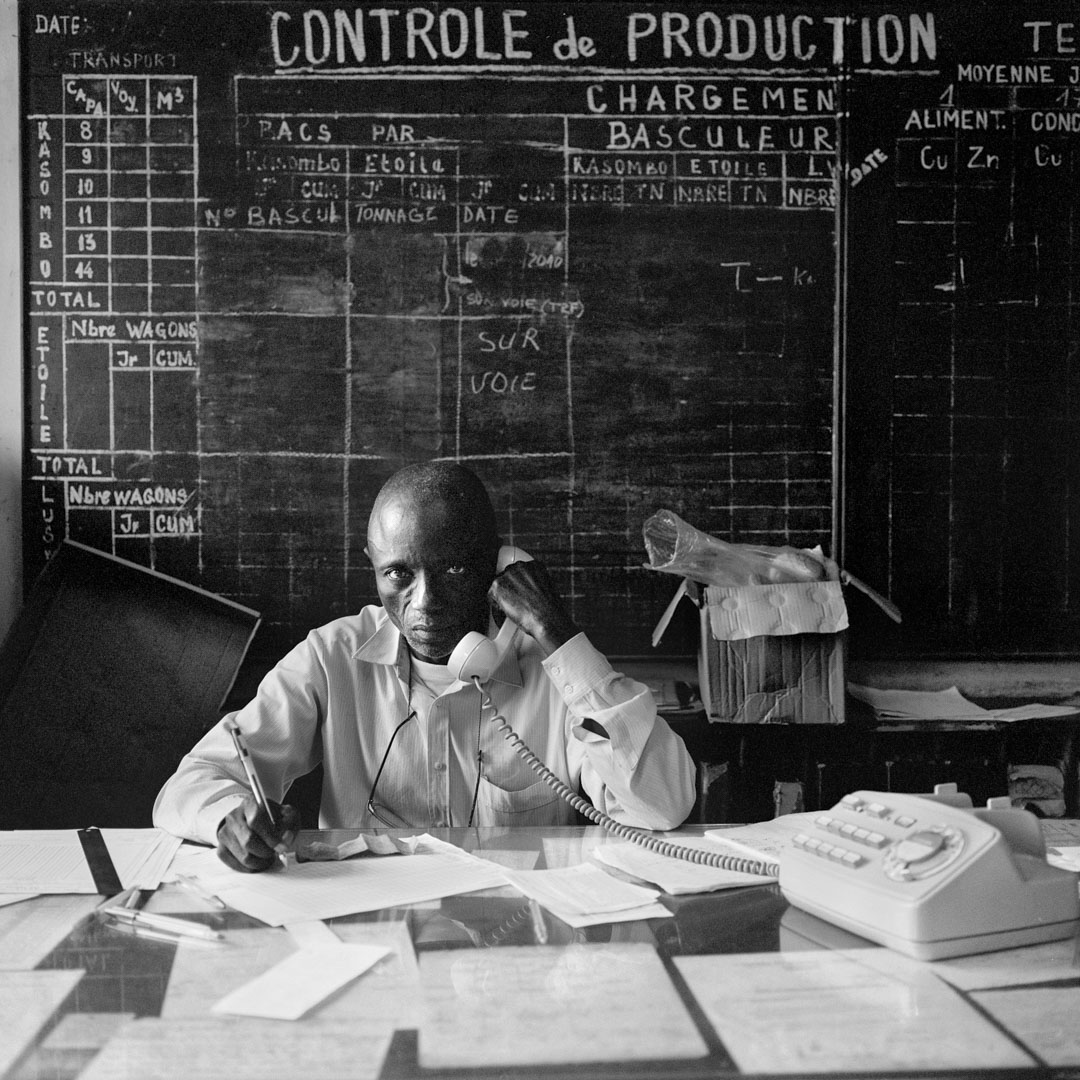

Congo in Limbo is Cédric Gerbehaye’s photographic essay on the Democratic Republic of Congo, the fruit of time spent on the ground and his rigorous commitment. His vision captures the complexity and intricacies of a little-known conflict.

In Congo in Limbo, nobody laughs. And that’s understandable. Anyone who has visited the country knows that laughter – the insolent defiance of joy in the face of tragedy – is a national pastime. And with good reason: Leopold II and the vile race for ivory and natural rubber, the troubles that followed independence, thirty-two years of Mobutu’s “kleptocracy”, and all that to fall into the hands of Kabila, first Senior, then Junior… It’s better to laugh than to cry! And, indeed, the Congo laughs and cries, except “at the frontier of hell”.

This is where Roman Catholic theology locates “the resting place of righteous souls”, who lived before the coming of Christ, and of children who die unbaptized. They must remain in limbo until the Savior’s second coming. In Congo, state borders limit this waiting room for the unfortunate. They are neither guilty nor innocent but, like their country, simply lost in transition: pushed into a cul-de-sac, put on the treadmill of history. They live in the past of a hope that never materialized, amid the ruins of a world they never built. They live in an eternal restart, waiting in vain for the big day.

Nyramana, 29, Nyanzale camp.

“Since November, we’ve been hearing gunfire every day. We spent many nights hiding in the bush, but the armed groups chased us and looted and destroyed everything we had in our house. That’s why we fled and settled here in the Nyanzale displaced persons camp. One day, I went back to our fields to get some food near Mihara. There, two men tried to rape me. We fought and they beat me with sticks until I was exhausted, at which point they raped me. I went for treatment because I was afraid I’d been contaminated. Now I’m afraid to tell my husband. I wouldn’t know where to start explaining it to him. I’m afraid he’ll repudiate me.”

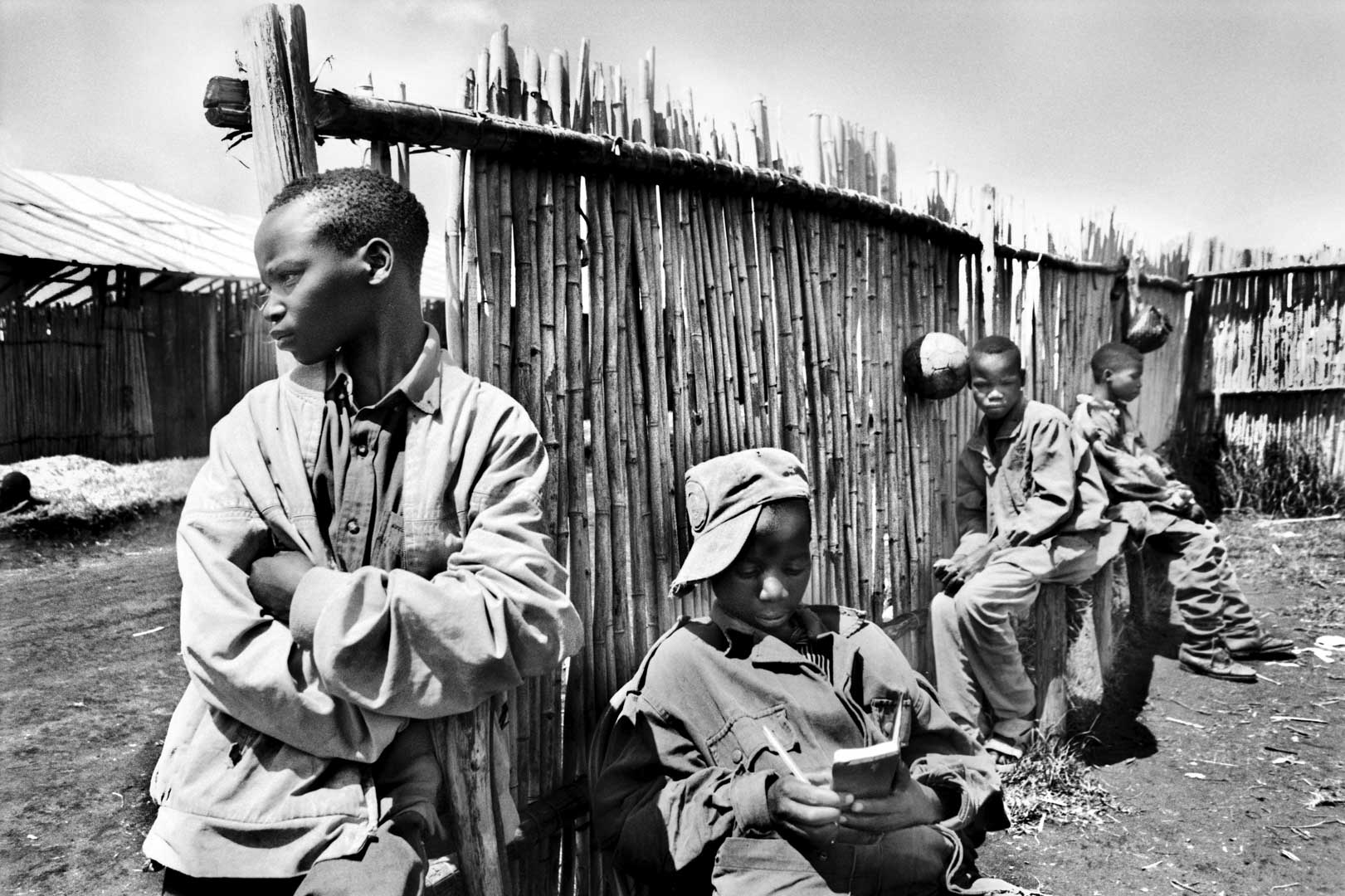

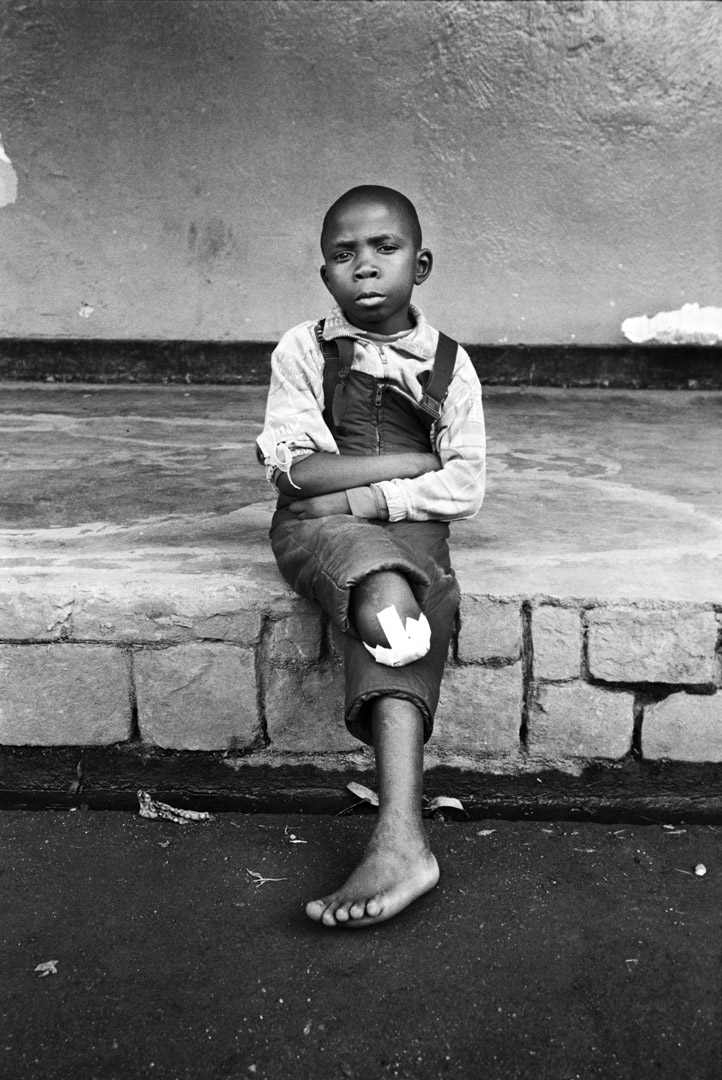

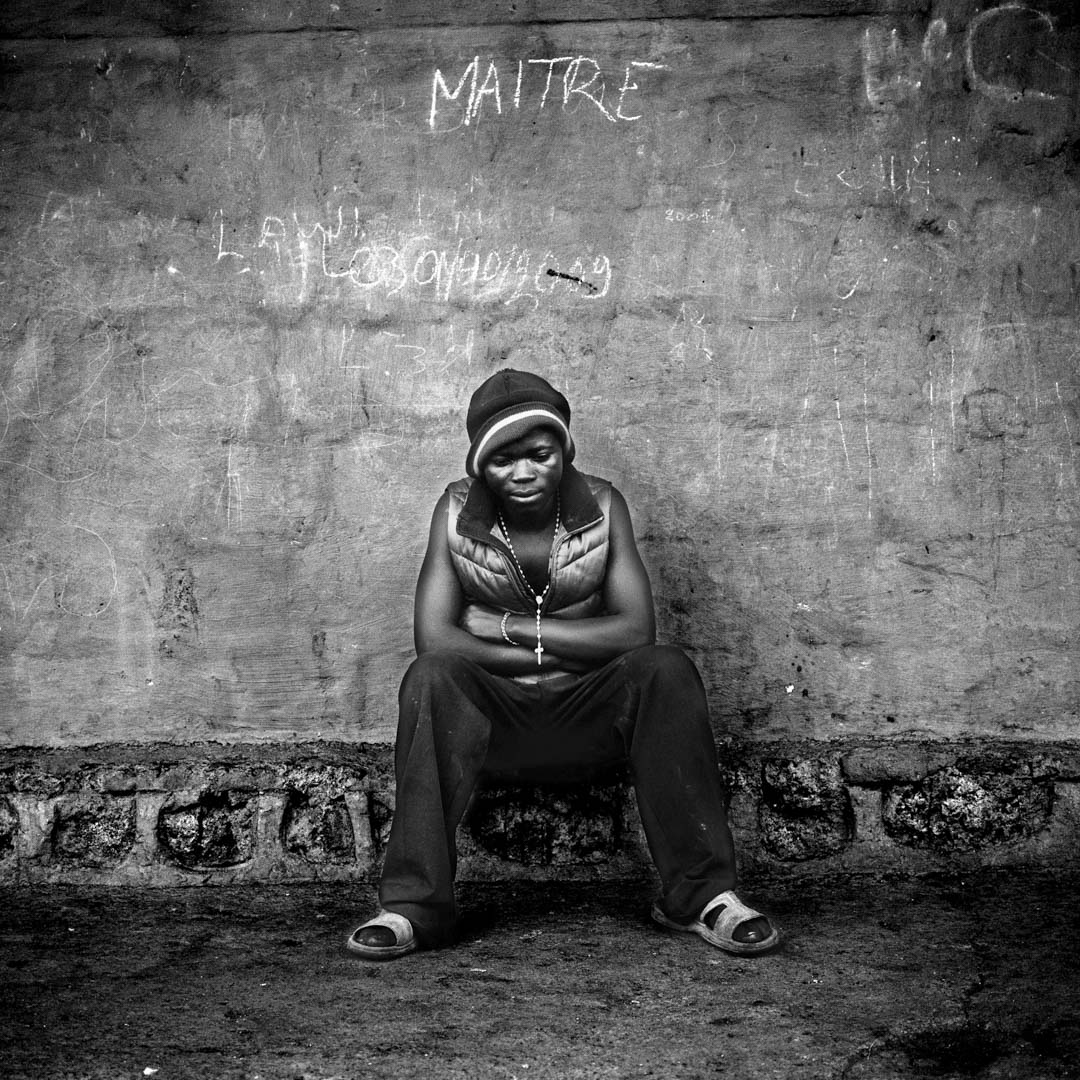

Joseph, 14, demobilized child soldier at the Don Bosco center in Goma, North Kivu.

“I was forced to join a Mayi Mayi group. I was injected with a talisman to avoid being hit by bullets. As a soldier, there’s nothing but suffering, no joy. Now I’d like to study and, if I get my degree, go on to university.”

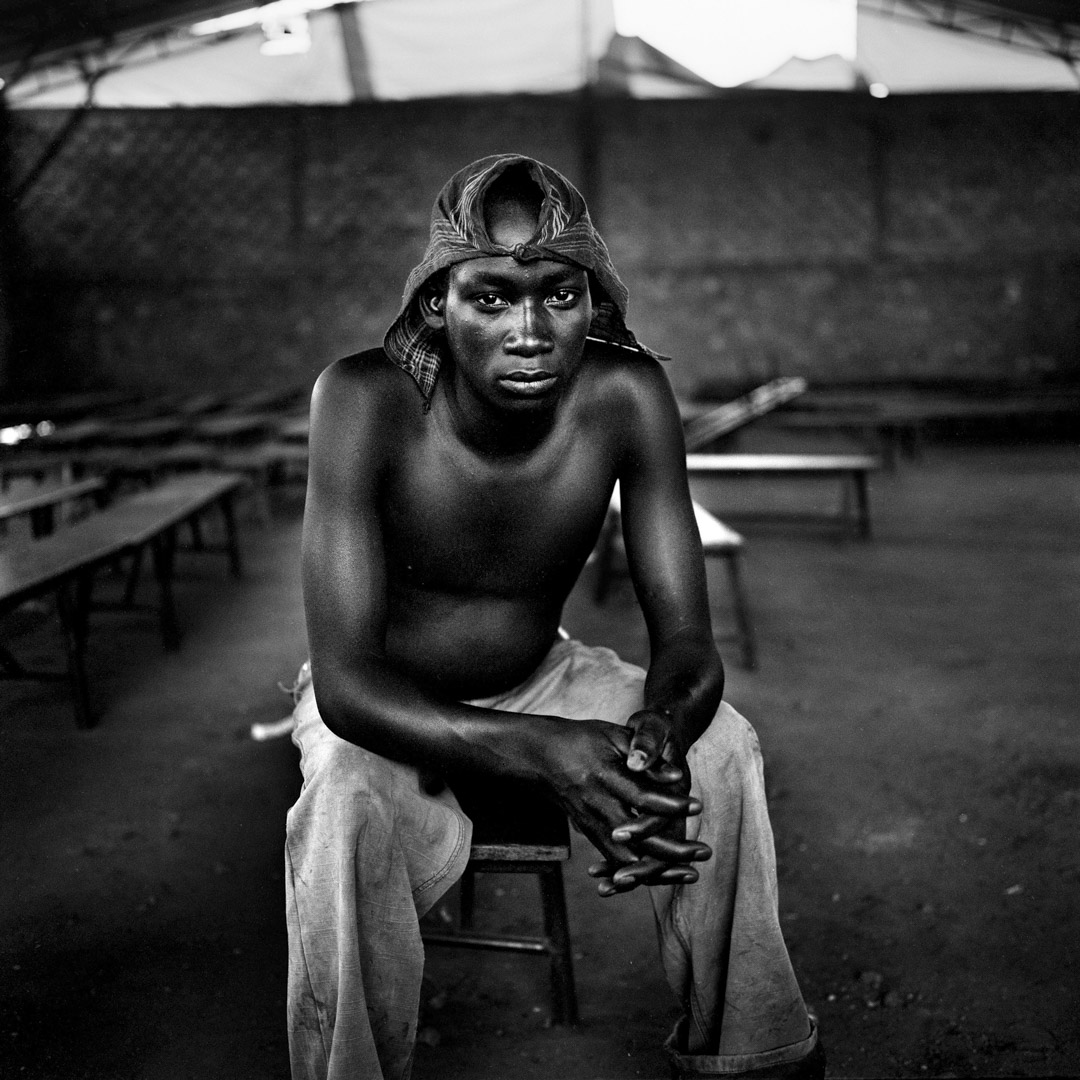

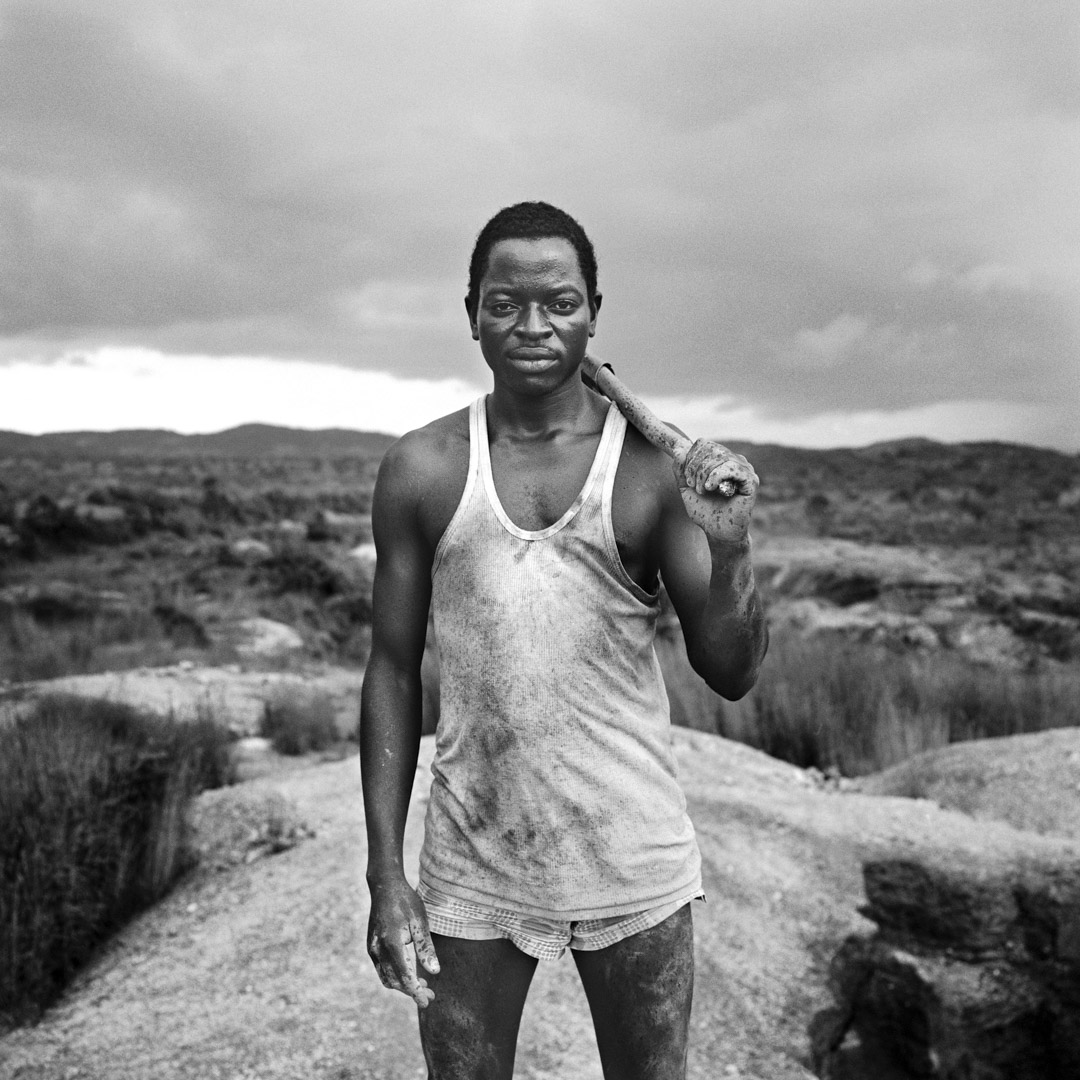

Moise, 14, demobilized child soldier at the Don Bosco center in Goma, North Kivu.

“I joined the CNDP of my own free will. I held my commander’s radio and carried no weapons except when he was asleep, when I held his weapon to guard him. After his death, the enemy pushed us all the way to Ngungu. It was a one-on-one fight and I was lucky enough to be sent to the river to draw water, and that’s when I was able to escape. Now I want to go home, because I have a field that my father left me when he died”.

Raymond, 14, demobilized child soldier at the Don Bosco center in Goma, North Kivu.

“I was in secondary 2 when we were told to join the PARECO (Patriotes Résistants Congolais). I was the colonel’s escort. I was in charge of a small group of young soldiers, and I was the one who placed them and no one had to speak. That’s how we got to the battlefield.”