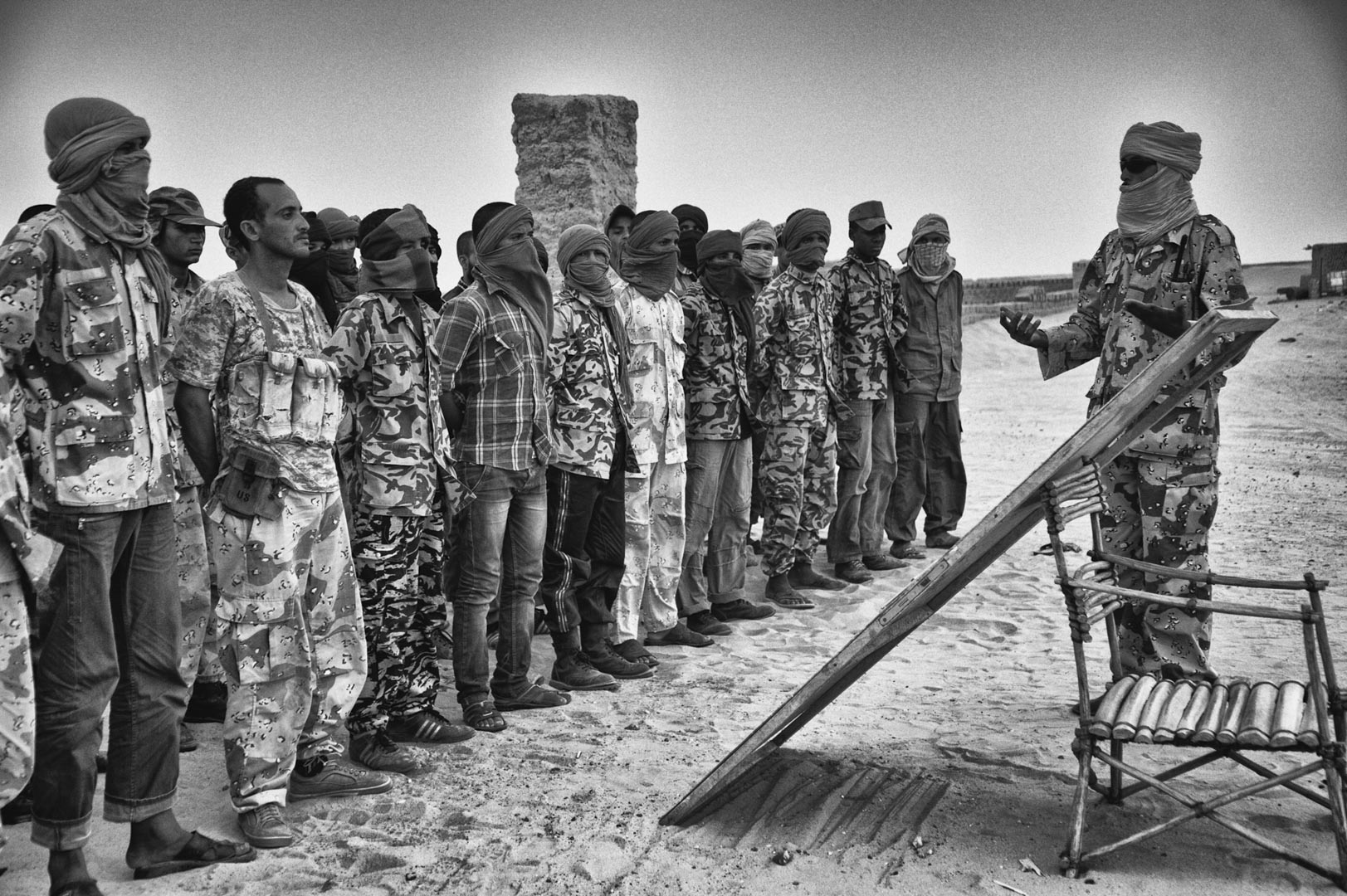

Berbers in North Mali, 2013

Ferhat Bouda has visited Kidal, fief of the Tuareg rebellion in North Mali, 1200 kilometers from Bamako, a major strategic stake and a mirror of local instability. His images powerfully testify to a situation that is as much in the media as it is little known; the daily life of the members of the independence movement: training of new recruits, securing their positions and the total administration of several towns and villages (Kidal, In Khalil, Tessalit etc.).

The zone controlled by the Tuareg independence fighters remains very dangerous because of the presence of groups of drug traffickers and jihadists on the ground. The MNLA, caught up in a multitude of intersecting conflicts, is actively recruiting to avoid assaults by Islamists. For the first time in the history of the Tuareg rebellion, women also decided to take up arms. Indeed, in this society, women enjoy an unequalled status: holders of knowledge and wealth, they are the guardians of traditions. From then on, their involvement in the military conflict is the sign of a new evolution of the rebellion.

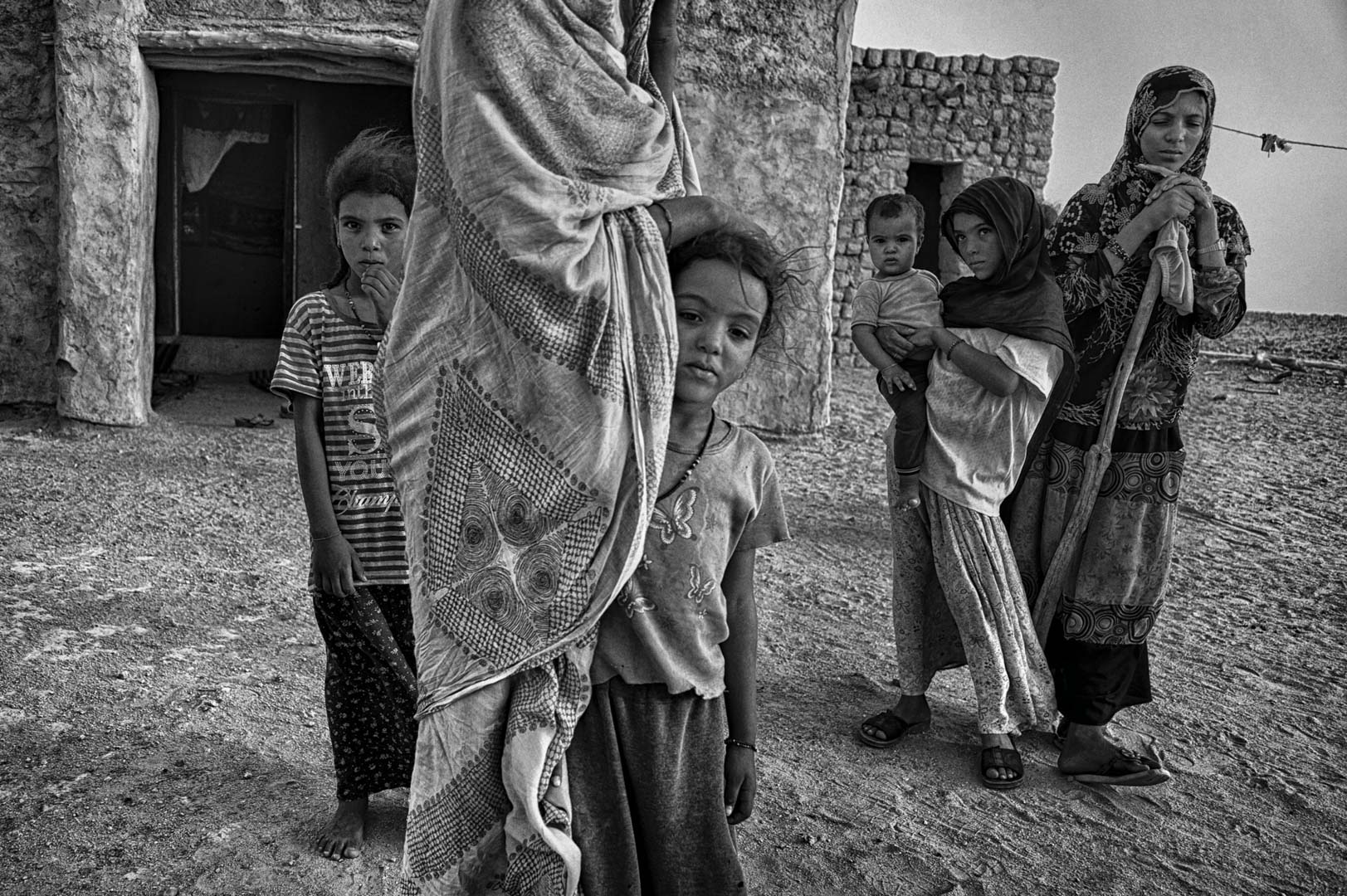

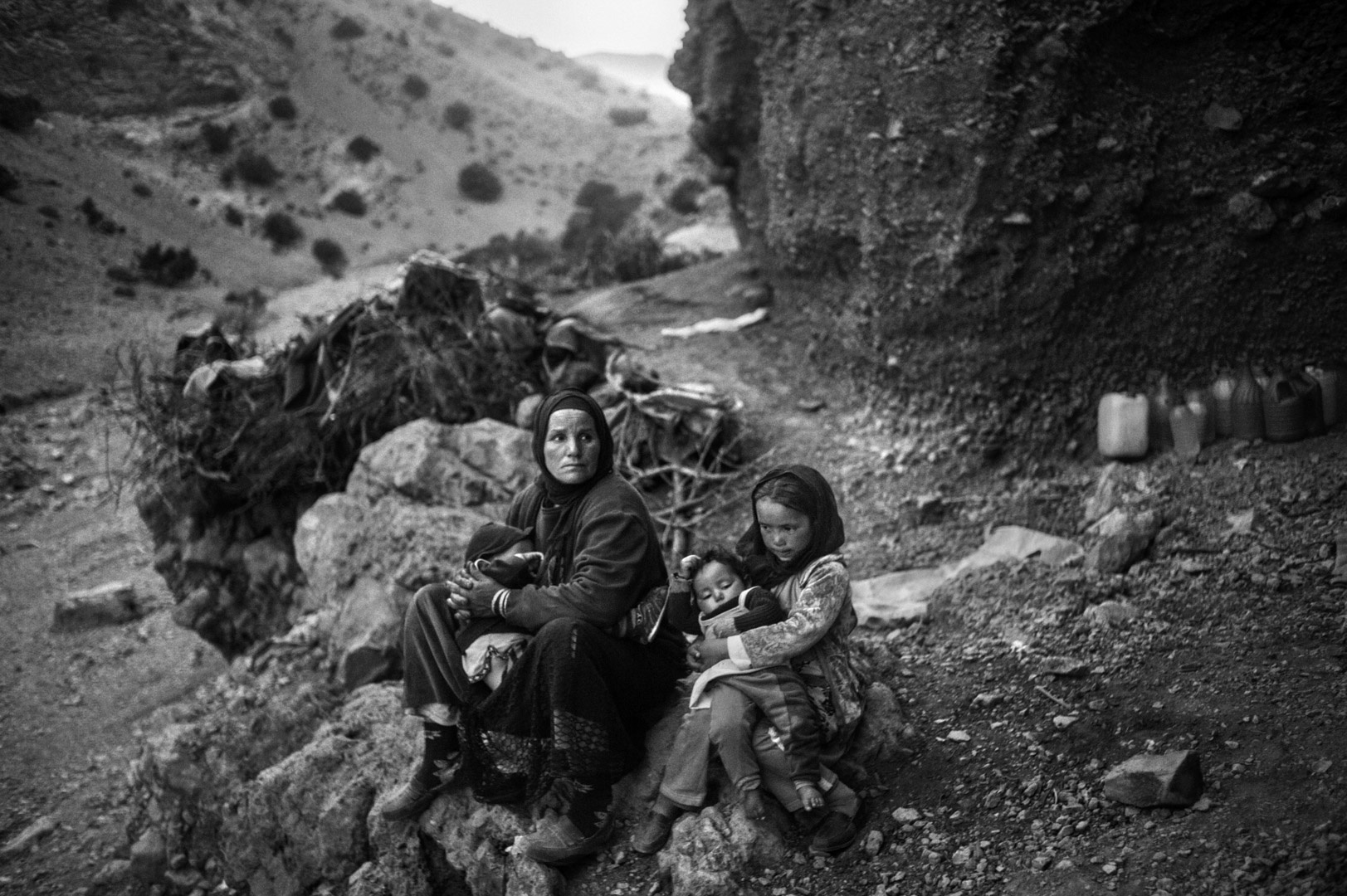

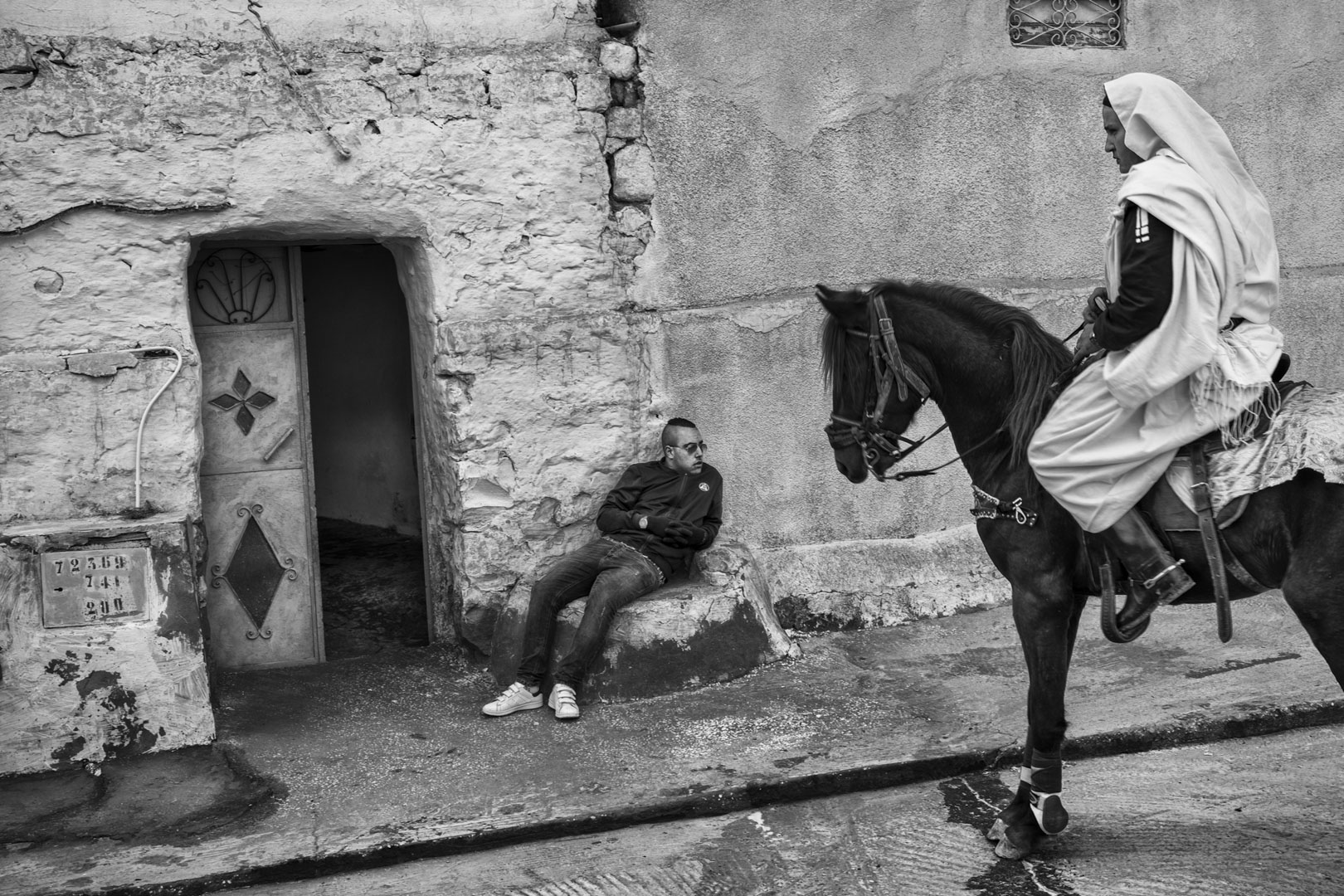

Berbers in Morocco, 2016

Most Berbers living in Morocco, Ferhat Bouda went to meet them in Tinfgam in the high Atlas Mountains, in the province of Tinghir and in Timetda. Whether they have settled in more or less isolated lands, Berbers all feel ostracized and purposely ignored by the local authorities. Despite the lack of infrastructure, their knowledge of the environment and their know-how enable them to be self-sufficient. Their way of life is intimately linked to the territory they live in and they organize themselves day by day according to the rhythm of nature. Deeply attached to their traditions, the Berbers of Morocco claim with determination their Amazigh identity.

This is an act of resistance against the assimilation and oblivion to which they are assigned. The hope and the future of these peoples thus rest entirely on the transmission to future generations of the values of this thousand-year-old culture.

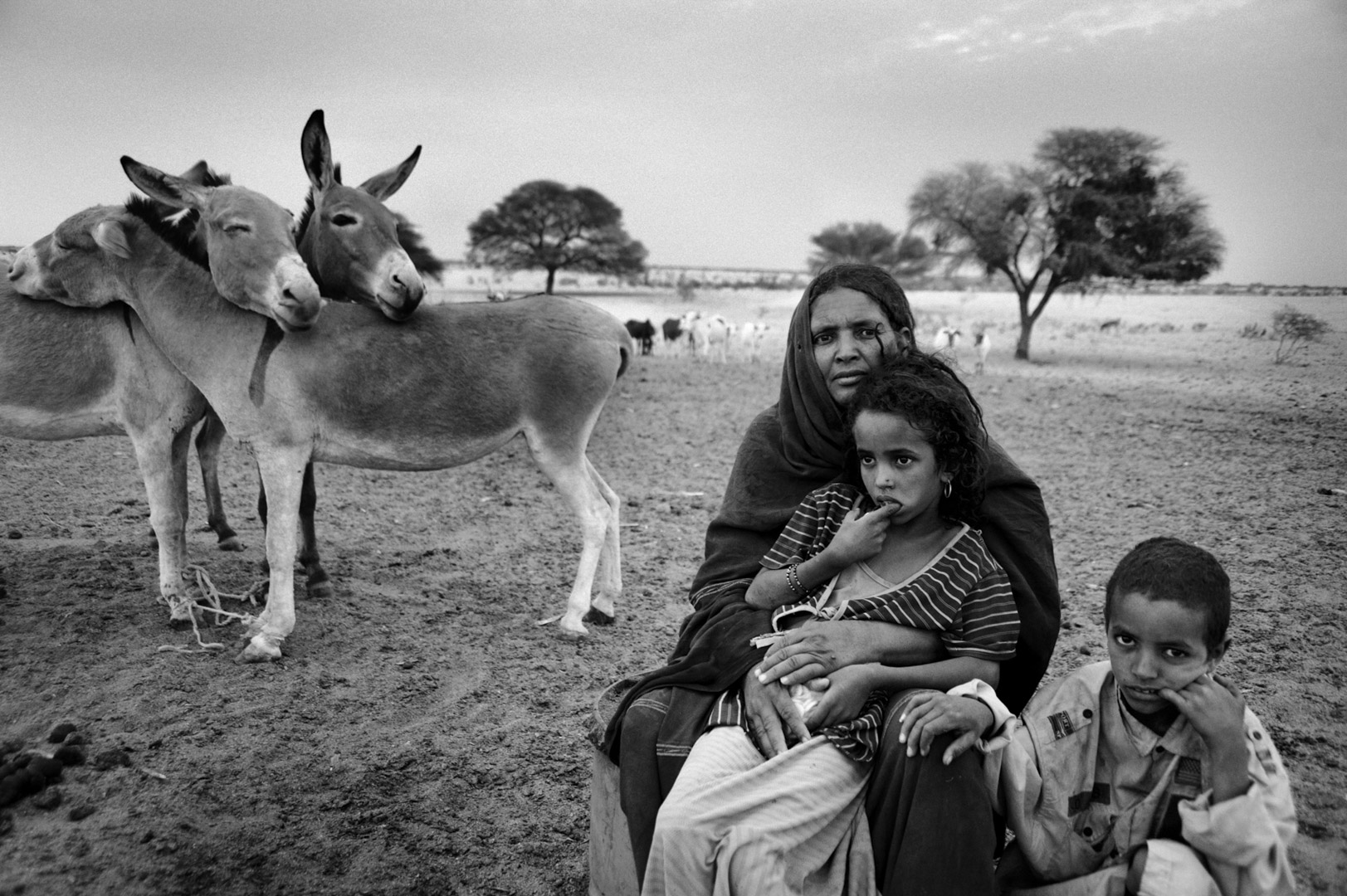

The Tuaregs of Niger, 2016

Ferhat Bouda went to meet Touareg tribes in Niger, around the cities of Agadez and Abalak. Taking advantage of the exceptional opening of the roads on the occasion of the country’s Independence Day, he was able to visit some areas that are usually very difficult to access and where insecurity is high. It is in the remote regions where the Tuareg camps are located, far from the influences of globalization and new technologies, that their culture remains intact. But the isolation is double-edged, since it exposes them to oblivion and indifference from the rest of the world at the same time.

“Tanmurt“, Algerian Berbers, 2017

“Tanmurt” means “Mother Earth” in the Berber language.

“Kabylia, a region in the north of Algeria, is my land, the one where I was born. Ever since I left my village, ghosts – ghosts that look like childhood memories – have been haunting me. However, I have returned many times, guided by the hope of finding these memories. But now life in Kabylia is dominated by death, love is replaced by hate and fear, and these communities are gradually transforming into a life of solitude.

In spite of the pain and sorrow I feel, I still have hope that I can make a positive difference”

Ferhat Bouda

The Siwis, Egyptian Berbers, 2017

In Egypt, the Amazighs are mainly concentrated in the Siwa oasis, close to the border with Libya. It is the only refuge of Berber culture in Egypt. This very isolated village was connected only in 1984 by an asphalt road to the nearest town, located 300 kilometers away.

Self-sufficient thanks to the abundance of water in the region, the Siwis live from their agriculture and shared knowledge. They are imbued with a rigorous Islamism that gives rhythm to life and traditions and strictly separates men and women. The women, on the bangs of society, rarely leave the family home and take care exclusively of the home and children. It is forbidden to photograph them and they must go out fully veiled, including their eyes.

Tunisian Berbers, A Minority In Margin, 2019

From the creation of the Tunisian Republic to today, the State, under the effect of a process of Arabization, refuses to recognize the Amazigh culture, because it is not part of the concept of a nation-state. The policy of marginalization began with the arrival in power of Habib Bourguiba in 1956, who saw Amazigh culture as a brake on modernity and by accelerating the process of urbanization, forced the Amazighs to leave their villages.

During Ben Ali’s presidency, the Amazighs were marginalized, largely on the basis that any identity claims that did not conform to a “single thought” were seen as a source of fracture with the nation. Since the revolution of 2011, associations for the defense of Amazigh culture have emerged and are leading a legal and media battle to advance the recognition of Berber specificity.