Looking for John Frum, Vanuatu, 1999

You could hear them before you could see them, these footsoldiers of John Frum.

In clammy equatorial heat, U-S-A scrawled in red paint on bare backs, wearing only blue jeans, they march in step. Soles thud on ground, hands slap on bamboo rifles tipped red for effect. The sound ripples around the rainforest valley at the southern tip of this far flung island of the South Pacific.

‘Forward march,’ barks the drill sergeant to his soldiers in the local Bislama language. ‘Present to the south. Present to the west. . . ‘

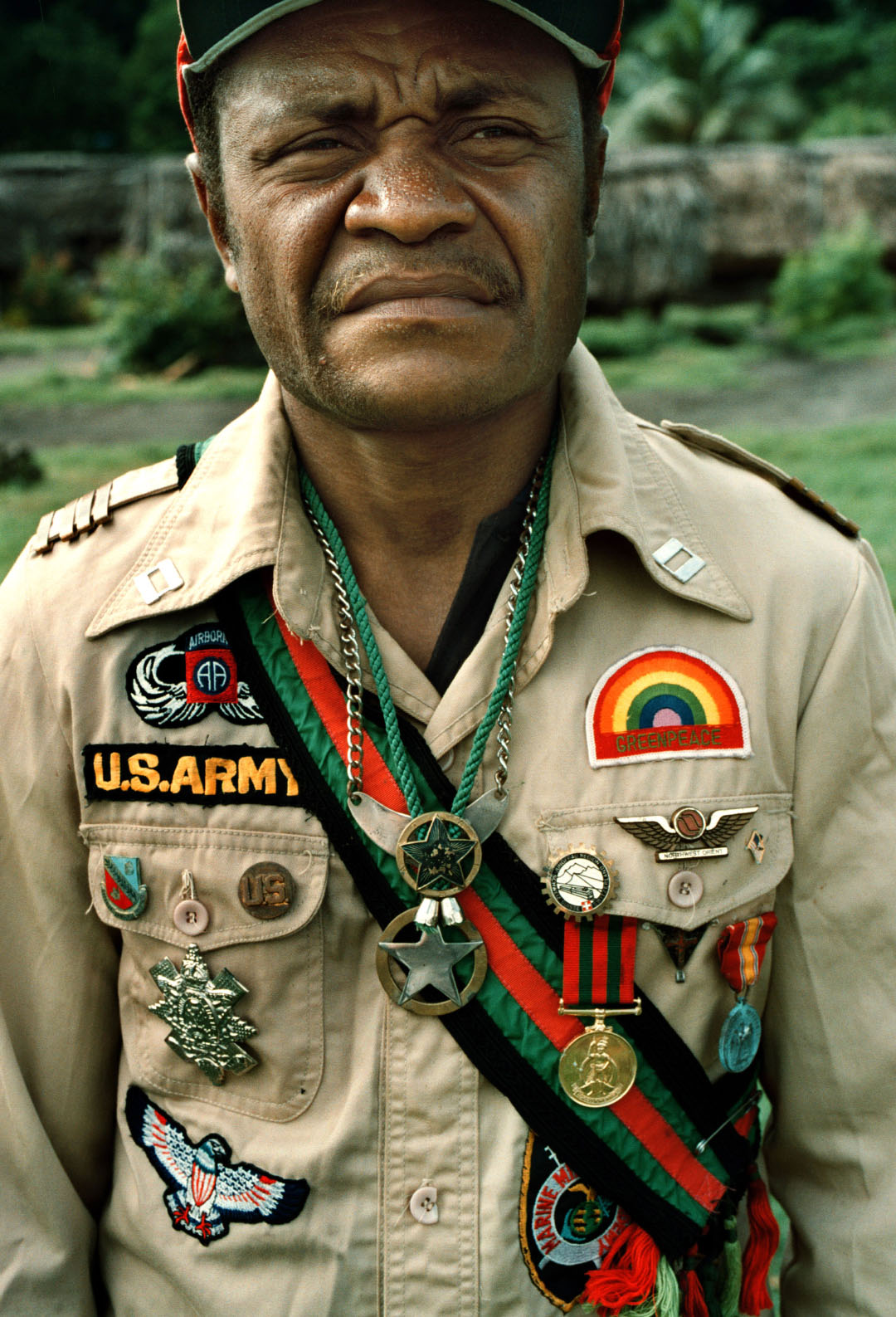

The men follow. It’s not quite the ramrod discipline of West Point, but straightbacked enough to be convincing. Screened by the rainforest, in a clearing where pigs roam, they have been practising drill since first light. They are young and proud. Chests puff out and jaws are struck firm. There is no military band, just the thud, thud, thud of feet, interspersed with the shouts of command. The movements are supervised by ‘officers’ dressed in khakis and resplendent with mock medals of military service and the epaulets and chevrons of rank and seniority.

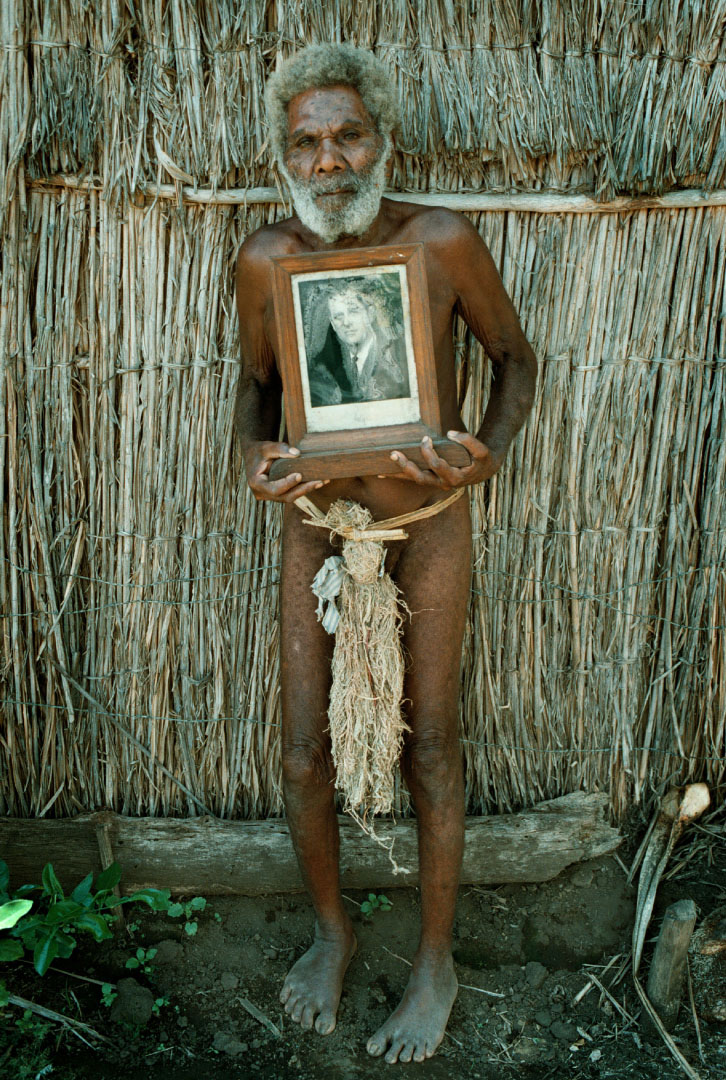

They have been parading like this since 1957, the national day of the John Frum movement, when the first American flag was hoisted on bamboo flag pole. The day commemorates a spiritual leader, John Frum, and a wartime ally, (the United States) that promised to return. Every February 15 the village leaders of Sulphur Bay, Vanuatu, raise the Stars and Stripes, now tatty and faded, along with the flag of the US Marines, the local provincial flag and the tricolour Georgian State flag bearing the Confederates ensign. The red cross, a symbol borrowed from the international aid organisation, sits in a tiny and humble prayer meeting hall across the field draped with yellow bells, hibiscus and marigolds.

Story by Linda Morris