500 coups, 1996

Due to Madagascar’s social structure and the disastrous state of it’s economy (ranked amongst the world’s poorest countries), more and more children have no choice but to live in the street. In Madagascar’s capital 4000 children aged between 2 and 18 years old live in the street, surviving in gangs, groups of up to 30 children which replace the family structure. They subsist by doing small, menial jobs in the market place, by begging, stealing and by prostitution.

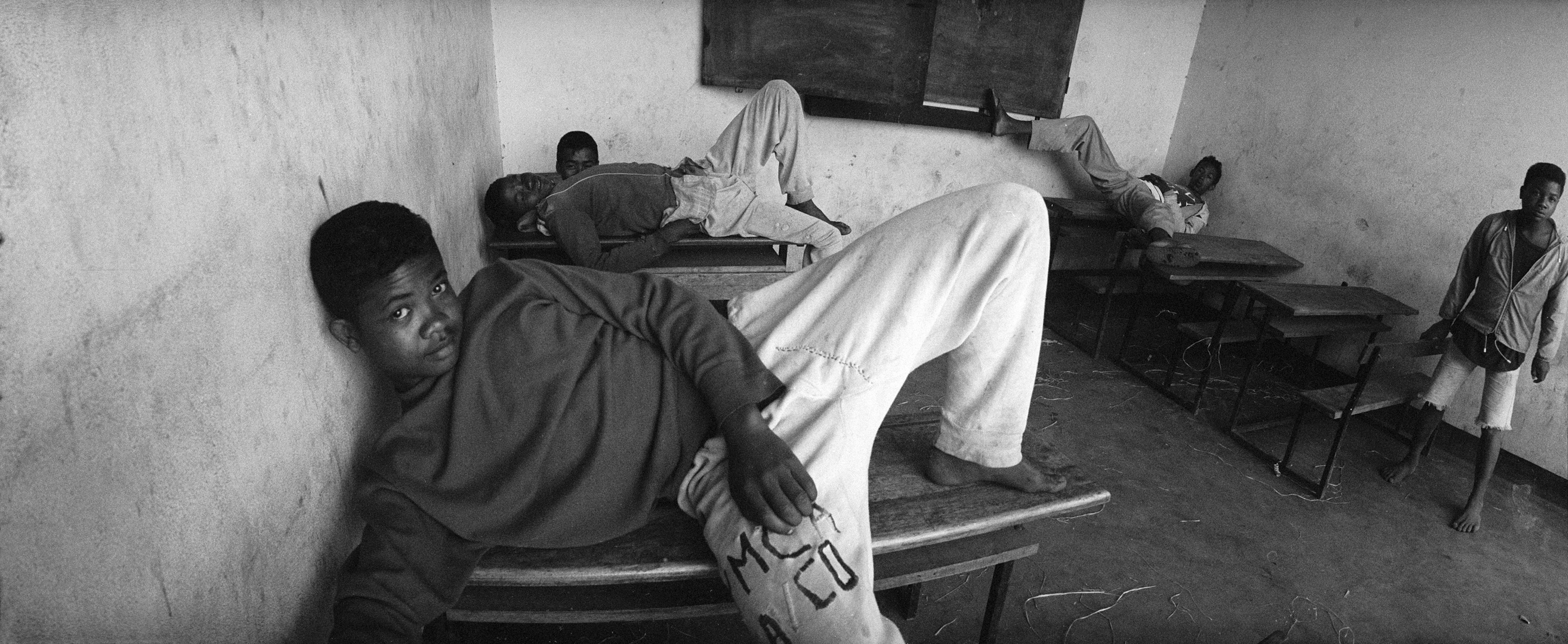

The local government’s solution to this ever growing mass of children is what is locally known as “rafles” – monthly night raids that take place during the tourist season or preceding a foreign dignitary’s visit. Due to pressure from various associations these raids had momentarily stopped in February 1996. The respite did not last long, last March 30 children were picked up in dustbin trucks, commonly known as “Bedfords” and incarcerated for indefinite periods in the local prisons whilst waiting for trial. With no clear charges against them, these children can wait for months, sometimes years before going before a judge.

Madagascar has two types of prisons, private and public. The public prisons are run and financed by the state. Here, the ex-prisoners who have finished their sentence can become wardens, they receive a salary and food, and in return they run and maintain order within the walls. These wardens take the large majority of food destined for the prisoners and maintain ‘law and order’ with makeshift clubs, knives and sticks. Malnutrition, stunted growth and the horror of everyday violence for these children, with an average age of 13, is considered normal by the authorities. Following a survey made by the humanitarian organisation Médicines Sans Frontières it appears that 50% of the inmates suffer from global malnutrition and 12% from severe malnutrition.

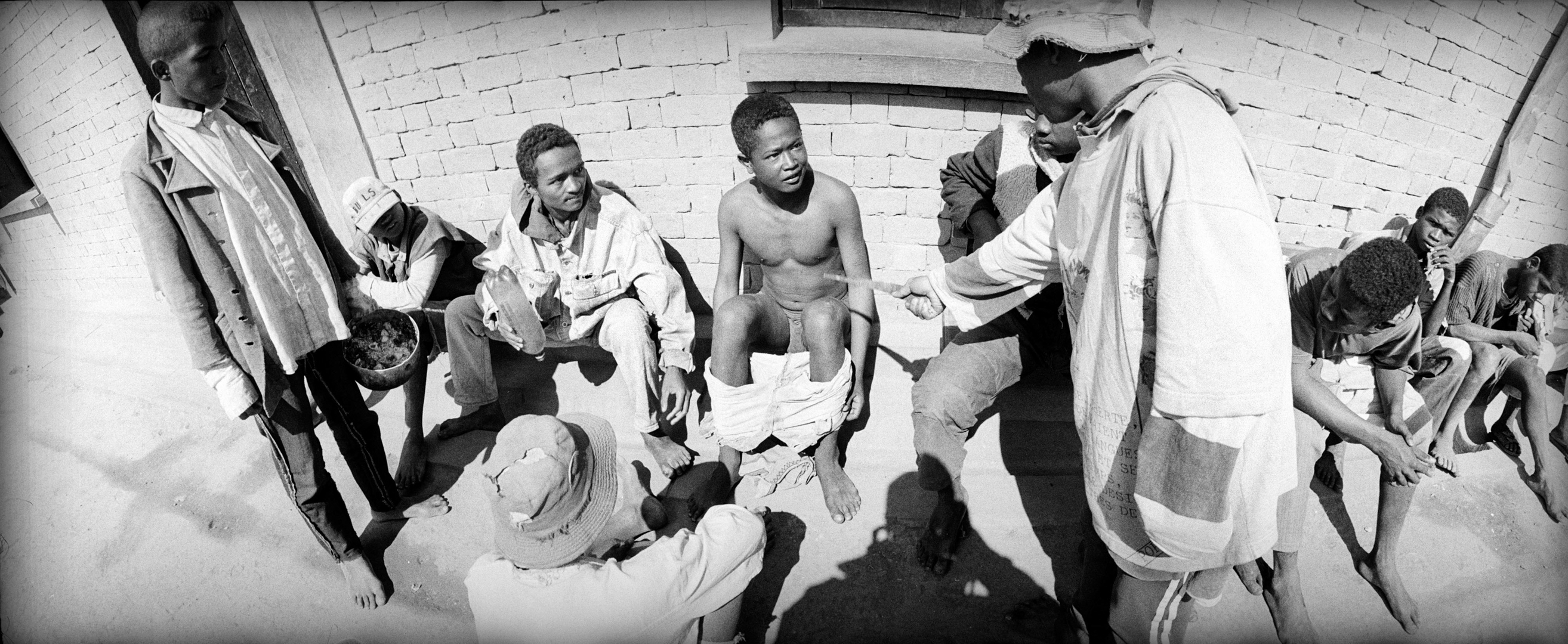

Private prisons are often run by families, funded by the state, donations and the work performed by the children imprisoned there. The conditions are the same as in closed prisons, except that the Director decides whether the prisoner deserves to be freed, with the knowledge that in doing so he looses free labour and a portion of the money allocated to him by the state for the prisoner (3500 Malagasy francs per day, roughly 5FF).

In these centres, physical and psychological punishment are dealt out to those who disobey, which is a sufficient reason to runaway by any means ; more children run away than are let out. But the reprisals are severe for those who get caught : “They made us walk on our knees from the road to here, they threw big stones at us and then beat us with sticks and electric wires”, explains Justin who tried to run away with two friends.

Even though Malagasy law is supposed to limit their preventive detention, once inside these centres it is almost impossible to leave. In one centre for example, the majority of the inmates are children picked off the capital’s streets in 1987, ten years ago; forgotten children who have lost all contact with their families.

“My life here doesn’t correspond to the life that I should have. If I was guilty, this punishment could be justified, all I can do now is wait.” – Solofo, inmate in a private prison.