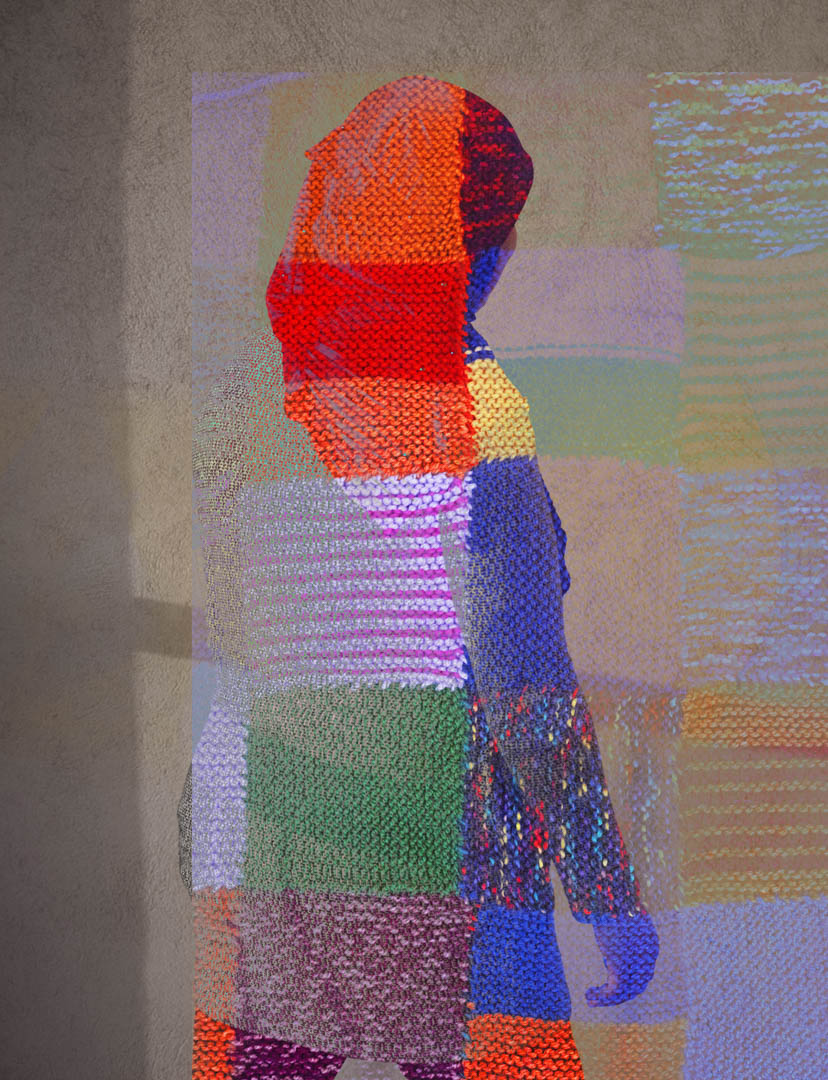

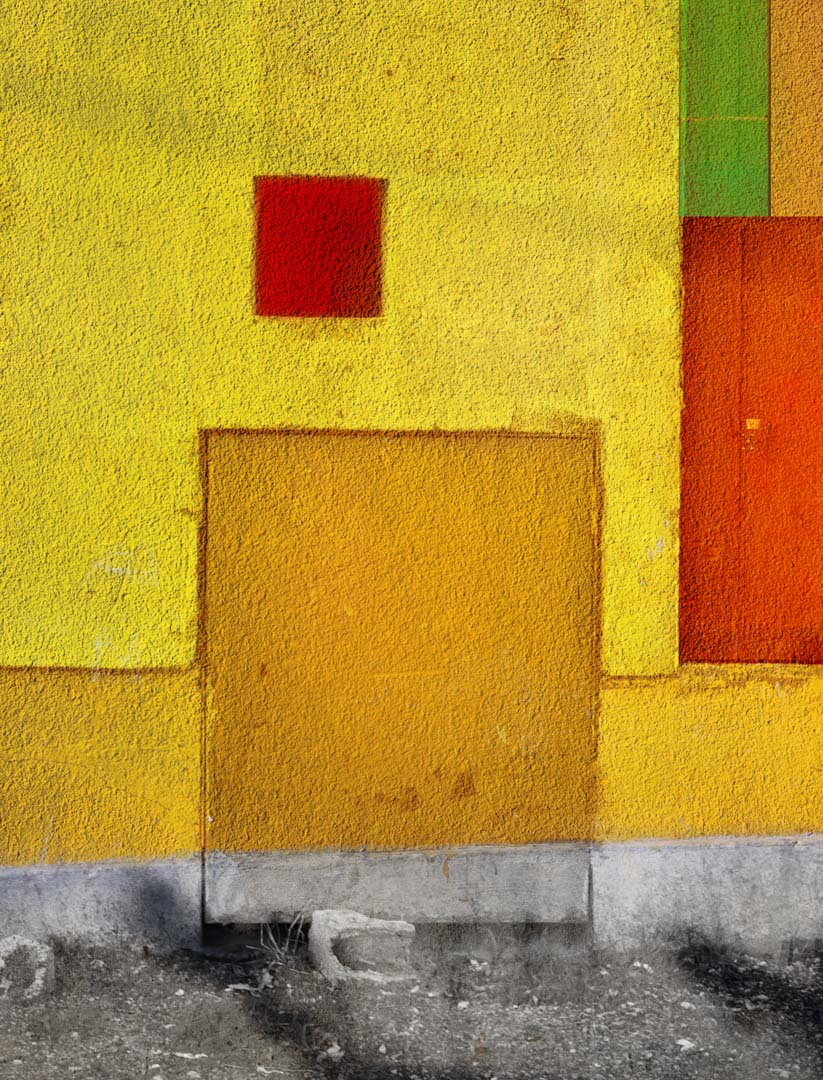

1.2.3 Soleil, 2019

A yellow rectangle, a red square One, two and then a whole series of silhouettes whose brightly coloured outfits echo the painted walls. Children in carnival masks caught in a bright light: rarely has the social question been posed with such a plastic bias borrowed from the language of abstract art. In the Griffeuille district of Arles, Tina Merandon succeeded in going beyond the image we have of others through a photographic experiment carried out in interaction with local residents.

First assumption: you know nothing about the commission given to Tina Merandon. Only the images come to you, in their plastic force; the choreography of silhouettes in dialogue with the architecture and above all the brilliant work on colour and materials impose themselves on you. Missing are the faces of a population whose reservations we can guess, but which in the logic developed by the artist manages to become a game: 1.2.3 Soleil. We wonder about the meaning of this aestheticisation of the place and its inhabitants.

Second hypothesis: you are aware of the nature of the commission, the social status of the Griffeuille housing estate, the influence of religion and tradition, the ordeal the photographer had to overcome to be accepted and, above all, to practise her art there. We admire the patience and trust, the value of the practices shared with the children, the bond forged with the women. And we think that today, photography has replaced all other forms of communication.

The third hypothesis is probably the right one. Tina Merandon asked herself: how can the social question be formulated in an aesthetic language? By turning the constraints into the beginnings of a formal lexicon (refusal to pose, an environment of dilapidated architecture, the impossibility of showing interiors) and then reducing this visual language to work with silhouettes, colours and materials. Tina Merandon manages to speak a living language of modernity. A language of colourful geometry, of an obsolescence that offers its materiality as a plastic ingredient: the whole resonates in a light that combines these elements in a kind of great tapestry.

The art historian then thinks of the painter Paul Klee, who, during his trip to Tunis in April 1914, admired the sober architecture of the houses, the power of the sun, the structuring capacity of colour and the strength of the woven wefts. The discovery of modern chromaticism by an avant-garde painter in North Africa echoes Tina Merandon’s photographic work. In the Griffeuille district, where the culture of the Maghreb vibrates, the plastic elements of a tradition seem to recompose reality. But the challenge is not just to nourish an artistic quest: here the social question is posed in aesthetic terms to change the way we look at things.

Michel Poivert 2020